- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Finding Hohokam Social Connections and Boundaries ...

(February 27, 2023)—Over the past four decades, the Hohokam region has become fertile ground for understanding social interactions at a large scale. Despite an ever-increasing cultural dataset, the region has largely escaped the big data revolution that has taken place in other areas of the Southwest, particularly the Ancestral Puebloan region. Until recently, archaeologists had yet to devote significant energy to amassing and synthesizing regional data from the Hohokam region.

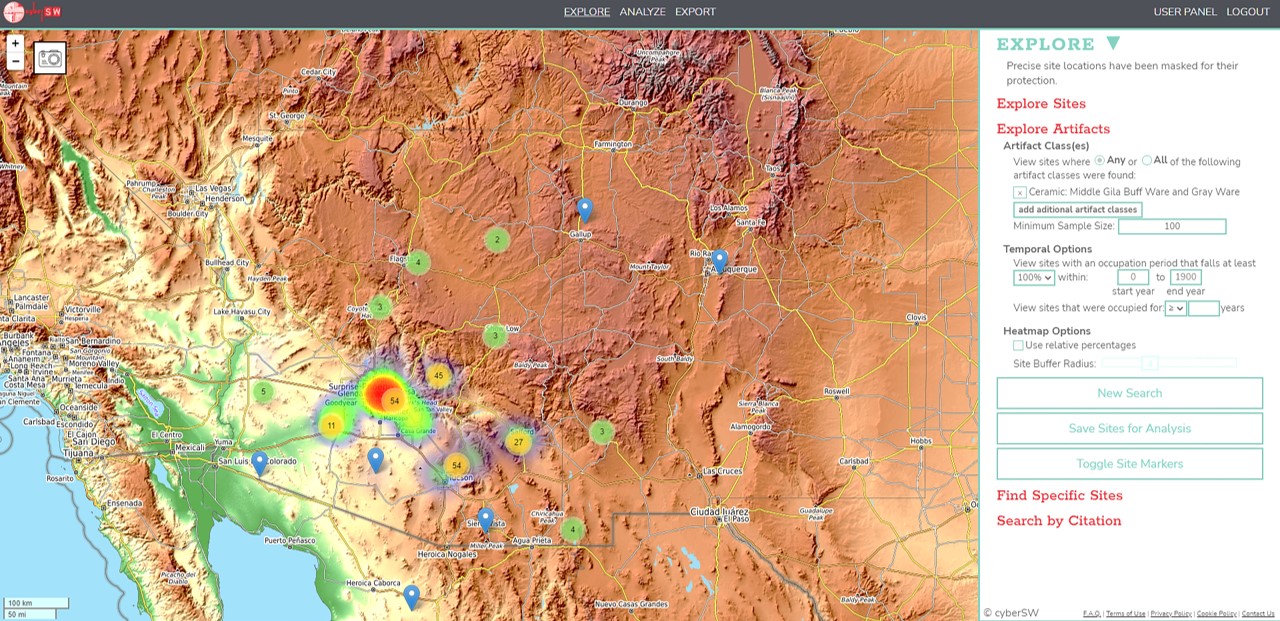

The powerful web-based tool cyberSW is on the verge of freeing Hohokam research from project-management boundaries and enabling us to understand Hohokam social connections in new and exciting ways. As we will discuss, cyberSW provides access to previously inaccessible data, but its full research potential has yet to be reached.

Scale and Constraints

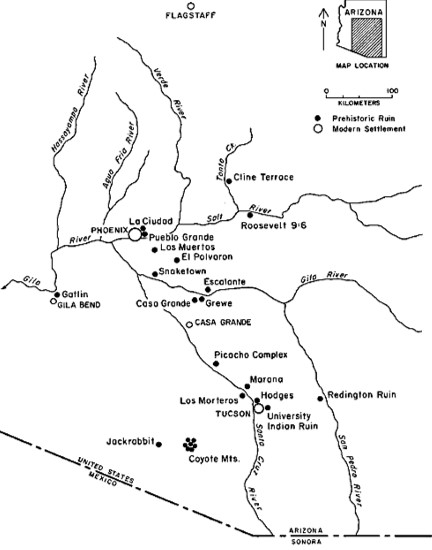

Anyone who has worked in the Hohokam region knows that archaeological practice there is necessarily different from other areas of the Southwest. With the exception of a few academic research projects, such as at Snaketown and the Casa Grande community, Hohokam research has been constrained by the boundaries, timelines, and goals of cultural resource management (CRM) projects. Although outstanding scholarship has come out of this milieu, such work has occurred in relative isolation.

Moreover, while there is an interest in synthetic studies, the scale of the data-mining challenge is daunting for researchers. Any attempt to aggregate data involves scouring disparate project reports and documents and reaching out to CRM companies.

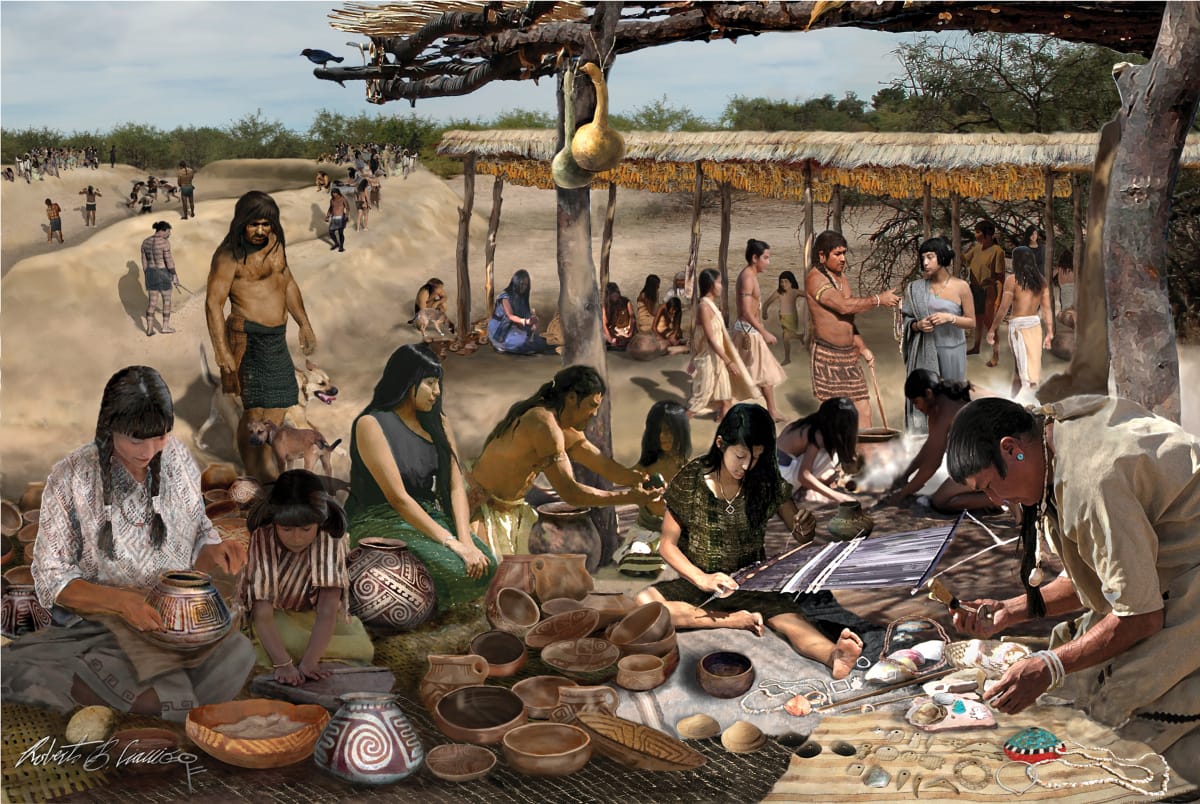

Archaeologists working in this region and time period have generally characterized social relationships as economic transactions. Regional marketplaces attached to ballgames facilitated people’s exchange of pots, crops, and other items, such as marine shell jewelry. Although the Hohokam region was vast, especially during the eleventh century (1000–1100 CE), studies of social relationships and trade connections have followed the pattern of compartmentalization that constrains Hohokam research in general.

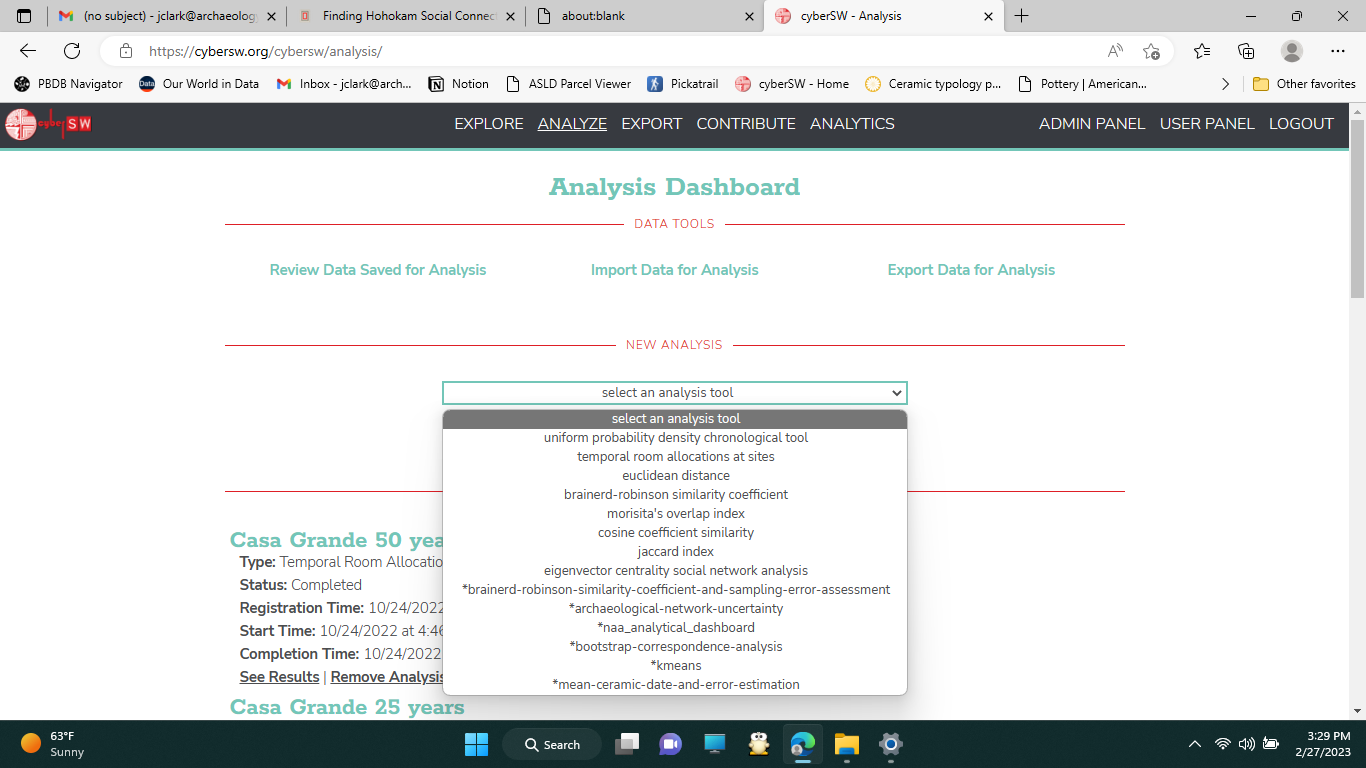

cyberSW and Distance Learning

During the fall 2022 semester at Arizona State University (ASU), Chris Caseldine offered a research apprenticeship program that aimed to find Hohokam social boundaries using cyberSW. While a postdoc at Archaeology Southwest, Chris learned about cyberSW and began testing its capabilities for Hohokam research. Although he could see its potential, gaps in data coverage limited its utility. By early to mid-2022, however, a concerted effort to accumulate data about Hohokam pottery had resulted in a more substantial database.

cyberSW does double duty as an academic research tool and a pathway for the public to engage with real archaeological data. Those dual goals make it ideal for students. Alex Malone and Em Lemaster, both online undergraduate students located in Tucson and Delaware, respectively, were selected to assist with the project. Over the course of the semester, the team met weekly over Zoom.

The current version of cyberSW presents ceramic data at the site level (all the pottery found at the site in aggregate), so Alex and Em also accessed CRM reports from the Digital Archaeological Record, or tDAR. This enabled them to record feature-level pottery data (information about pottery found within different parts of a site, in features such as pits, structures, courtyards, and so on).

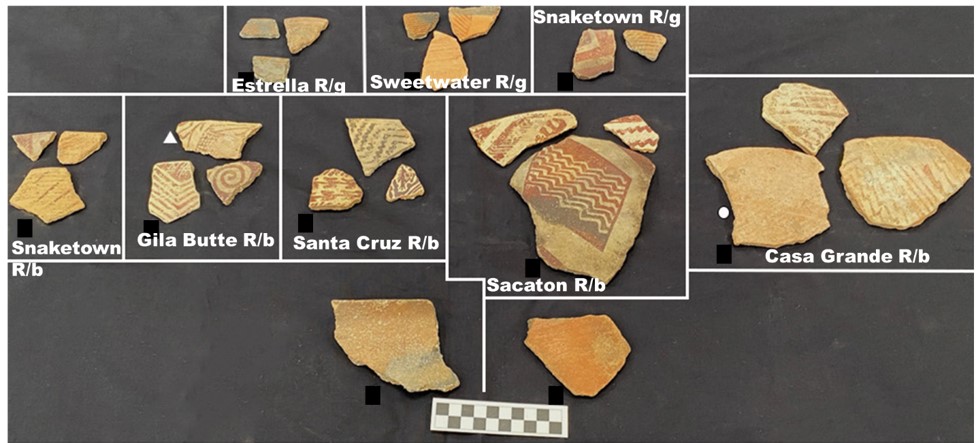

People inhabited large Hohokam sites like S’edav Va’aki (Pueblo Grande) for centuries, so aggregated site-level data would obscure changes in social connections through time. For example, a household living during the height of the ballcourt marketplace system is treated as equal to a household living in the same settlement several generations later during the height of platform mound ceremonialism, despite having different kinds of decorated pottery (Middle Gila Buff Ware vs. Roosevelt Red Ware). The site reports available through tDAR allowed for a more in-depth look into the patterns than cyberSW was able to provide. This shortcoming will be resolved in the next version of cyberSW through reports provided by tDAR and other sources.

Pottery Sherds, Data Tables, and Social Connections

Two research questions guided our study. First, do available pottery data allow us to identify social boundaries within and between irrigation systems? Second, what is the nature of Hohokam identity in Tonto Basin?

Buff ware pottery is a quintessential marker of the Hohokam archaeological pattern. Within the Southwest, this kind of pottery is interpreted as evidence of Hohokam presence or as an indication of strong ties to the Hohokam region. It is also something that cyberSW is equipped to explore.

Among lower Salt River irrigation systems, in-field observations during excavation projects indicated that settlements south of the lower Salt maintained exchange relationships with middle Gila River potters after the region became socially fragmented around 1100 CE.

In the Tonto Basin, intrepid Hohokam farmers set out from the Phoenix Basin and colonized the area, initiating long-term settlements. Work during the Tonto Creek Archaeological Project, conducted by Desert Archaeology, Inc., documented supposed Hohokam settlements in the lower Tonto Basin that did not easily fit the typical Hohokam pattern.

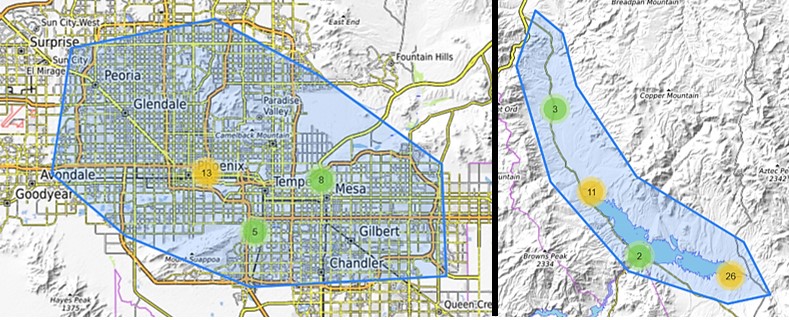

For our study, we created polygons around the lower Salt River valley and Tonto Basin. Then we searched cyberSW for ceramic data for pottery made between 650 and 1300 CE, the period when potters were producing Middle Gila Buff Ware and the preceding red-on-gray pottery.

In addition to heat maps that show the distribution of ceramic types and obsidian sources, cyberSW allows for advanced statistical analyses. Our review of available statistical options indicated that the Brainerd-Robinson similarity coefficient would serve as a good starting point. We used a score of 100 as a similarity threshold, where 0 indicates no similarity among pottery assemblages and 200 denotes perfect similarity. Using the cyberSW dataset, we found that settlements only crossed the 100-score threshold with sites in their same vicinity.

The striking aspect of our analysis was that the aggregated dataset indicated sites were more similar to their own area, either the lower Salt or Tonto Basin, than with settlements from the other area. For example, Meddler Point, located in Tonto Basin, had at least one pithouse courtyard group (typical of the Hohokam residential pattern) and a relatively high frequency of buff ware pottery, so one would expect that it should cross the 100-score threshold with at least one settlement on the lower Salt River. The analysis, however, revealed that its pottery assemblage was different from sites along the lower Salt.

A cursory review of the Meddler Point complex ceramic assemblage shows a diversity and frequency of white wares (pottery produced to the north and east and through different traditions) not seen along the lower Salt River. As noted by archaeologist David Doyel, at sites in the Phoenix Basin, such nonlocal pottery accounts for less than 1 percent of a site’s ceramic assemblage. Although there is little evidence for groups from the east or north joining settlements in the lower Salt River valley, Tonto Basin did experience a rapid demographic expansion around 1200 CE, possibly accompanied by migrants, particularly from the Kayenta region.

Zooming into each area, the similarity analysis revealed differing insights. Whereas settlements in the Tonto Basin were more likely to have greater pottery similarity with sites in their regional neighborhood, only slightly more than half of the lower Salt River sites had stronger ceramic similarities with settlements from the same side of the river. These results do give credence to observed cultural divisions within Tonto Basin, but the same was not true for the lower Salt.

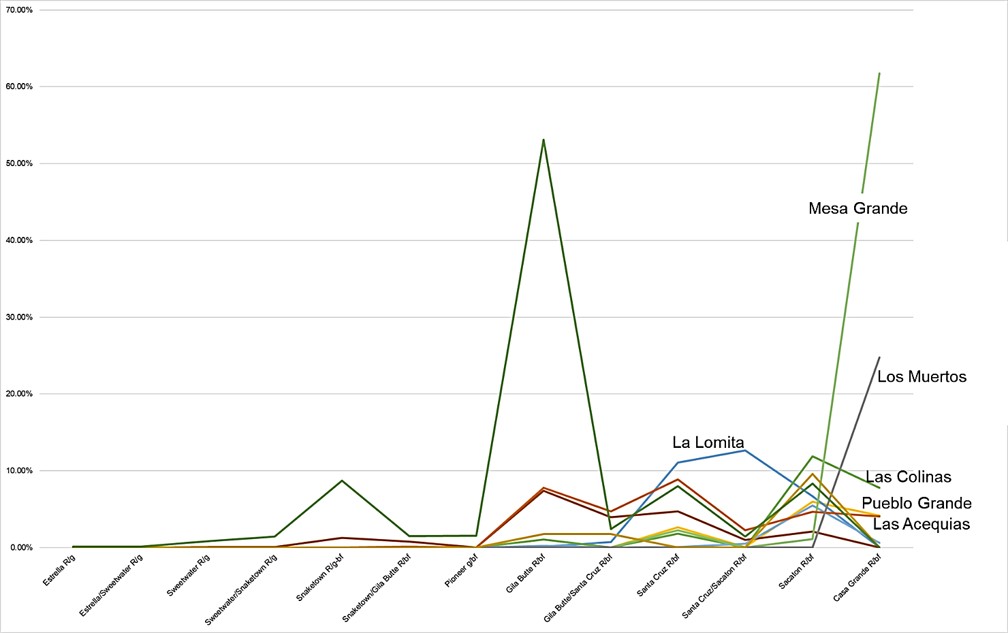

Stepping away from the similarity analysis and focusing on just Middle Gila Buff Ware frequencies for the lower Salt, it does appear that buff ware exchange decreased over time north of the river. While north-side villages like S’edav Va’aki (Pueblo Grande), La Ciudad, and Las Colinas saw a decline in buff ware frequency leading up to the production of Casa Grande Red-on-buff, settlements south of the river, like Mesa Grande and Los Muertos saw an increase.

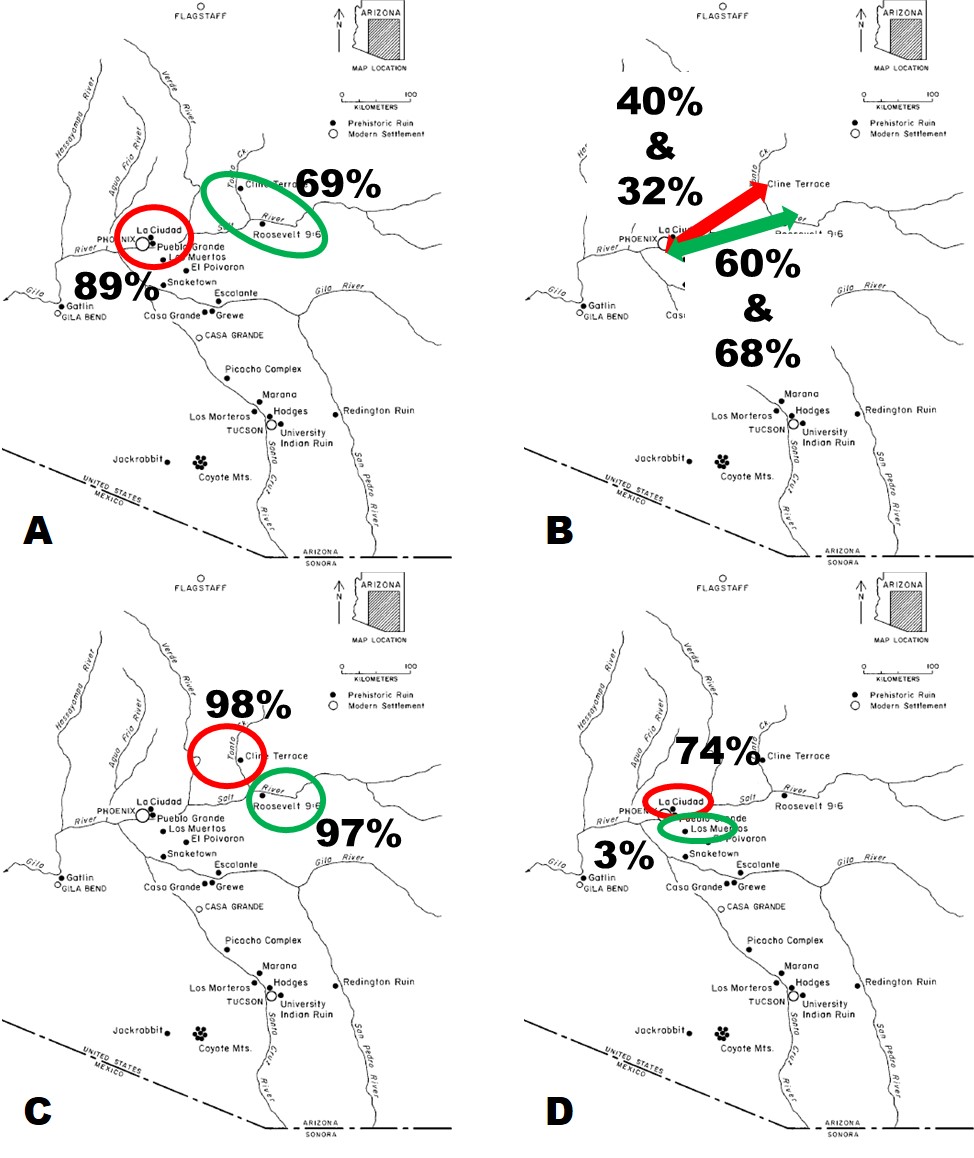

The limitations of cyberSW ceramic data were made clear when we carried out the second part of our project, in which we undertook Brainerd-Robinson similarity analyses for data collected from reports available on tDAR. By treating each archaeological feature as an individual entity, the area solidarity seen in the cyberSW data started to fall apart. Where lower Salt River valley feature ceramic assemblages were more similar to features in that area 89 percent of the time, this was true only 69 percent of the time for Tonto Basin. Further drilling down, both sides of the lower Salt River had feature pottery assemblages more similar to Tonto Basin settlements along the Salt River, than they did to Tonto Basin settlements along Tonto Creek—a result that corroborates the interpretation that people on the Salt “arm” ascribed to Hohokam identity more so than on the Tonto “arm.”

In the lower Salt River valley, the feature pottery assemblages revealed that features north of the river commonly shared similarity with other features on that side, but south of the river the features, and the people who created them, did not restrict themselves to that side. It appears that social boundaries that structured irrigation system and settlement memberships may have played a lesser role in ceramic exchange than previously thought.

Reflections and Looking Ahead

Our project represents a first step toward unlocking insights into Hohokam archaeology not easily possible even a few years ago. As we discussed, the current version of cyberSW is hindered by limitations associated with site-level ceramic data. Although the ability to construct settlement chronologies and reliable demographics is yet to come, cyberSW did a reasonable job pointing toward some general trends for further investigation. Of particular importance for us, cyberSW and tDAR provided a medium for engaging in archaeological research without being in the same room, let alone the same state.

Work on this particular project ended with the completion of the fall semester. The planned next phase is to start examining settlements in the Tonto Basin to better understand the nature and complexity of Hohokam identity. Part of this phase will be sourcing Middle Gila Buff Ware collected from sites there to understand where people in Tonto Basin were getting that pottery—whether from settlements along the banks of the middle Gila River, Queen Creek, or another production location.

We therefore encourage you to use cyberSW not just as an interesting curiosity—it does make really interesting maps—but also as a place to start your research, whether you are a seasoned archaeologist or an archaeological enthusiast.