- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Making and Cataloguing Jewelry

(July 15, 2024)—Although I would not consider myself to be a particularly stylish person, I can recognize beauty in other people’s wardrobes. Fashion is not usually something people think about when considering the past. It is easy to assume that clothing was simply practical, designed purely for protection against the elements. One thing that quickly disproves that notion, though, is the presence of jewelry. It serves no practical purpose other than to be beautiful and shows that people cared about what they were wearing.

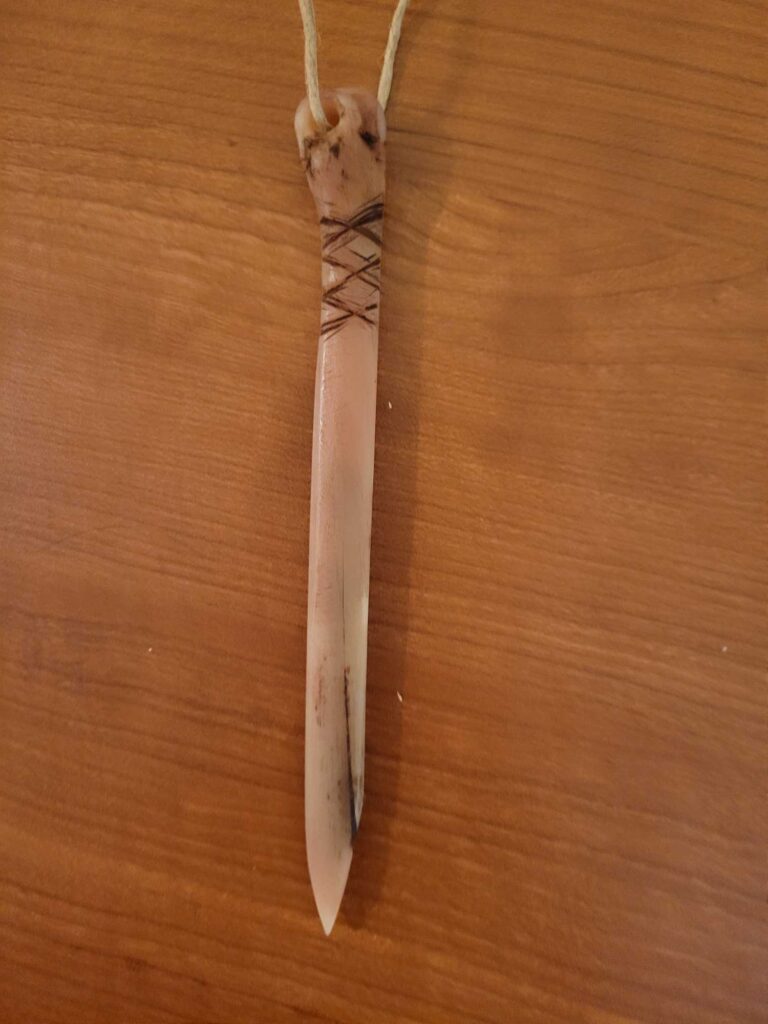

During our very first day at the Western New Mexico University Museum, a display case full of beads, pendants, and bracelets caught my eye. So did a small selection of bone awls, large enough to be used as hairpins. They enchanted me so much that during my experimental archeology rotation in Cliff, I replicated my very own awl and pendants. Creating my own jewelry by wearing down hard serpentine on a slab of sandstone and scraping off sinew bits from a real bone was difficult. It took a long time and gave me a blister on my palm. That experience gave me a new sense of appreciation for how talented the ancient jewelry makers of this region were.

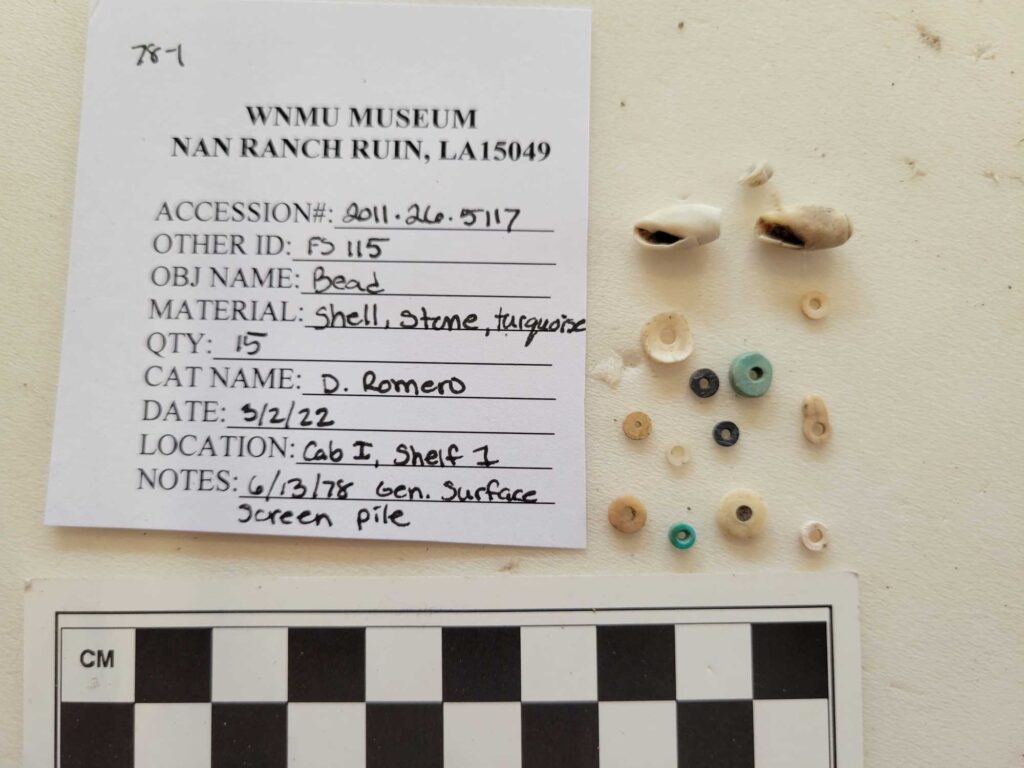

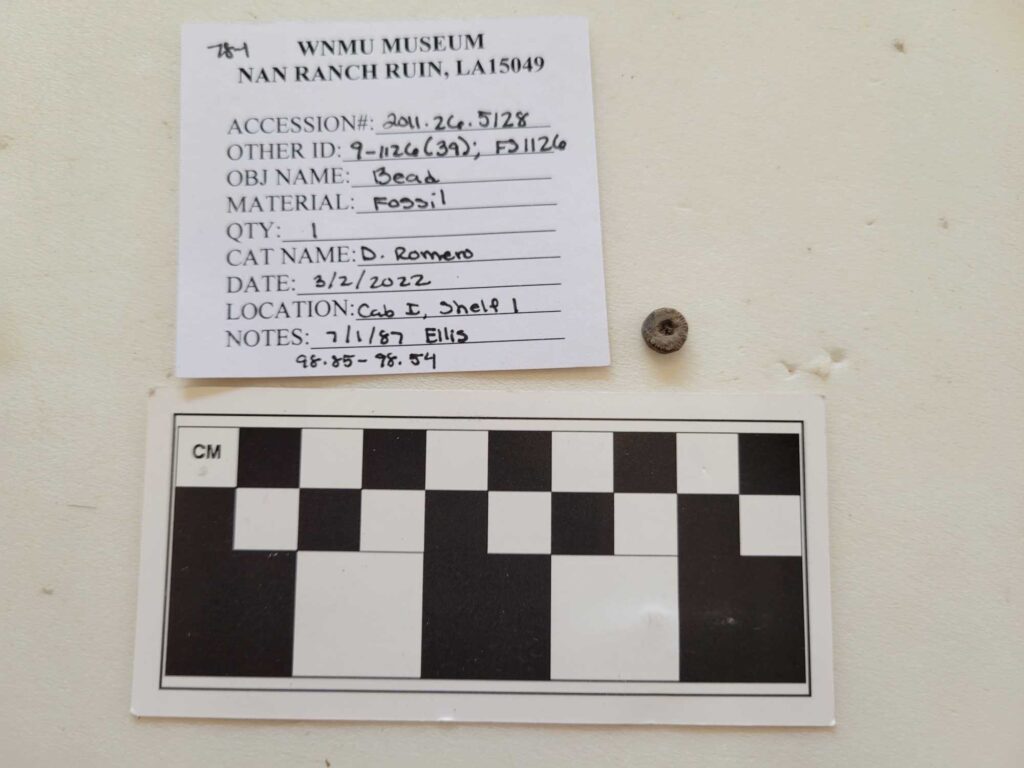

After I returned from Cliff and started working at the museum again, I wanted to learn more about this jewelry. The museum director, Dani Romero, was nice enough to bring me the collection boxes of jewelry. What I found in those boxes was an overwhelming diversity of styles, materials, and sizes. There were some beads so small that they could only be found by floatation (a sifting method which uses water to float up very light materials such as plant matter or bone). My favorite two beads were made out of crinoid fossils. There was a lot of jewelry made out of different shells, many of which had a unique spiral shape. There were also beads made out of turquoise, talc, and other unidentifiable stones. Although none at the museum had animal shapes, one pendant excavated at the nearby Mattocks Ruin was in the shape of a small bird. Throughout my research for this blog post, I felt perpetually in awe at the creativity and skill of the jewelry makers of the Mimbres tradition.

I believe that the study of clothing, jewelry, and other personal adornment is important to the study of archaeology because it reminds us to humanize the people of the past. They are not simply something to study as though they are a curiosity or a puzzle. And despite them living thousands of years before us, without writing, globalization, metallurgy, or the internet, they are still humans. Looking at all this jewelry at the museum, I wondered whether one of them was someone’s favorite bracelet. I wondered if best friends made beads for each other. I wondered how quickly their fashions came and went. I wondered whether someone ever felt embarrassed because they didn’t have the coolest type of shell. At the end of the day, I am an archaeologist because I love humans, not their things.

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.