- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- New Research on Old Turkeys in the Mimbres Area

(September 2, 2024)—One of the many fun and interesting things I got to do this summer while working at the WNMU Museum with our Preservation Archaeology Field School team was a rapid assessment of some of the faunal remains (animal bone) recovered at the NAN Ranch site. People lived in this village during what we call the Late Pithouse and Mimbres periods (750–1130 CE). Like all our analyses this summer, this work focused on a specific group of excavated rooms that form one of the household groups Harry Shafer identified in his work with the Texas A&M University field school from the 1970s though the early 1990s.

Our team checked each bag of fauna and noted how many fragments it contained and what classes or orders of animals (artiodactyls, lagomorphs, rodents, birds, reptiles, amphibians, or fish) the bones came from, along with anything else that stood out in our quick examination. All of this information went into the museum’s catalog system as we rehoused the fauna in new archival-quality bags. We also removed anything that wasn’t an animal bone and made sure it was rehoused where it belonged. This will make it much easier for future analysts to search the collection and choose samples to focus on.

I couldn’t resist inventorying the boxes of partially articulated animals from the collection, even though they weren’t from our sample area. These consisted of groups of bones from the same animal, found grouped together when they were excavated. Some were just a handful of bones, like 5 elements from a bird in the jay family. Others represented most of a skeleton and were found lying next to each other in positions suggesting either a whole animal or an animal part, like a bird leg or wing. Most were not animal burials (animals placed in a pit or other specific area with a funerary connotation), although a few may have been.

Among the partial animals in one of those boxes were several turkeys. Field school student Cassie Merrill found these turkeys—and the turkey images on Mimbres Classic period bowls—so interesting that she did her class research poster on turkey bones and imagery in the Mimbres region.

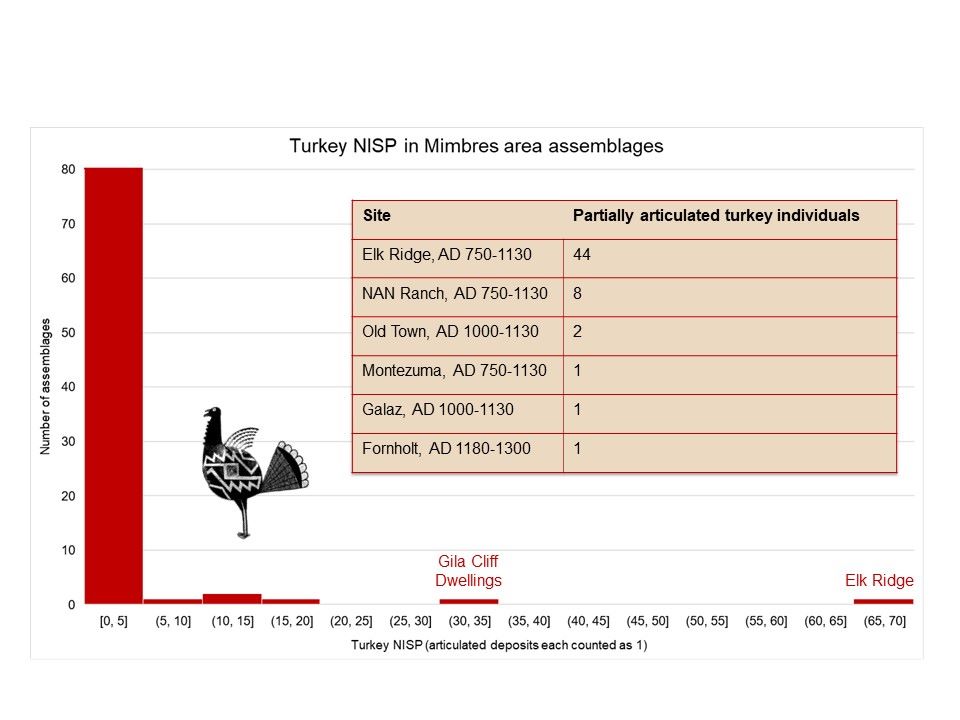

I was also pretty excited to see these turkeys, as I’d read about them in publications about NAN Ranch and been curious about them for a while. Most animal bone assemblages, or groups of bones, from archaeological sites in the Mimbres area contain fewer than five turkey bones, and the vast majority have none at all. A poster I presented with my colleagues Amanda Semanko and Martin Welker at this year’s Society for American Archaeology annual meeting has a handy graphic that summarizes this. Although NAN Ranch has more turkeys than most villages—a few individual bones and 8 partially articulated birds, according to published reports—I’ve also been fortunate to work on the animal bone assemblage from a village with many more of them: Elk Ridge.

The Elk Ridge village is from the same time period as the NAN Ranch site and located partly on private land and partly on Forest Service land; I worked on the fauna from a 1990s excavation on the private side, and a later excavation on the Forest Service side is still being analyzed by Barbara Roth and others at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. When I began studying the animal bones from Elk Ridge, I knew that there would be more turkey bones than I was used to seeing. Several decades ago, a student analyzed some of the turkey remains there and presented a conference paper on them, suggesting there were about 17 individual turkeys from the excavations. To my great surprise, I ended up finding the remains of at least 44 semi-articulated turkeys and dozens more isolated turkey bones!

Examining this abundance of turkeys showed some pretty interesting things. One specific leg bone (the tarsometatarsus) suggests the sex of a turkey. Birds with a sharp, bony spur on that bone are most likely male and those without it most likely female (although, like many things, this attribute of turkeys exists on a continuum and not as two discrete categories). Of the tarsometatarsi complete enough to check for a spur, half had one and half did not (6 individual turkeys from each category).

Amanda and I measured all of the bones that weren’t too broken, collecting a standard set of measurements we can use to compare the sizes of these birds to others from ancient Southwestern villages. Our measurements show that the turkeys with tarsometatarsus spurs were larger than those without spurs. Three of the birds had healed injuries to large wing or leg bones, something archaeologists have noted from other villages where people used lots of turkeys.

The near-absence of turkeys from most Mimbres-area villages suggests people didn’t use them very much. Even at Elk Ridge, most turkey remains (95%) were from birds left semi-articulated in uninhabited rooms in the village. In contrast, animals that people ate a lot of (like rabbits) have many hundreds or thousands of broken pieces of bone scattered throughout every village, in both indoor and outdoor trash deposits. Turkey bones in the Mimbres area also don’t generally show evidence of burning or cut marks from stone tools, which are much more common on other animals that were butchered and cooked.

In the Four Corners area, zooarchaeologists use similar reasoning to infer that people weren’t eating turkeys on a regular basis until after about 1000 CE, but instead raised them for feathers to make blankets and other items. Turkeys in the Mimbres area were also most likely wanted for their feathers. There’s been some very interesting research on turkey feather blankets lately (for example, see articles by Mary Motah Weahkee and by Bill Lipe in Archaeology Southwest Magazine’s recent issue on birds).

Why are there so many more turkey bones at Elk Ridge than at other Mimbres villages? Perhaps people there chose to spend more of their time obtaining turkey feathers or making turkey-feather items, and exchanged those with people in other villages who focused on different resources. There’s archaeological evidence that people in certain Mimbres villages did choose to produce more of certain things, such as wild grapes, pottery, or fermented drinks, and sometimes exchanged these products with their neighbors.

Did people raise turkeys at Elk Ridge or NAN Ranch, or were all of these birds hunted? Archaeologists have used several lines of evidence to figure this out. One is looking for turkey pens, and recent work by Cyler Conrad discusses some of the ways archaeologists may recognize those facilities. In the Mimbres area, very few structures fit these criteria. Because many of the birds in Mimbres villages were found in rooms people had stopped living in, some excavators have interpreted those rooms as turkey pens, but I doubt anyone finding a dead animal in its pen would just leave it lying in there.

I think people harvested the valuable feathers and then placed the turkey bodies in unused rooms because the dead animals needed to be disposed of somewhere out of the way, but didn’t belong in “ordinary” refuse areas where people threw the remains of their everyday meals. There’s also no turkey poop in these rooms, unlike in the Four Corners area where turkey pens are filled with layer upon layer of the stuff. The empty rooms gradually filled with other disused items and soil that washed and blew in, and eventually their roofs collapsed.

Another way to tell whether people raised the turkeys they used is to determine whether they were wild or domesticated animals through genetic testing. In the ancient Southwest, domesticated turkeys have a maternal genetic lineage distinct from local wild turkeys (the subspecies Meleagris gallopavo merriami and mexicana) and more similar to birds from populations east of the Rio Grande (M. gallopavo intermedia and silvestris). Sean Dolan and colleagues recently analyzed the mitochondrial DNA from 18 turkey bones from Mimbres villages. Their sample included 15 bones from Elk Ridge, and 10 of those were from domesticated turkeys.

It’s interesting that all the domesticated turkeys in their sample were from Elk Ridge, the village with by far the most turkeys in the Mimbres area. It’s also interesting that Elk Ridge still had a generous proportion of wild birds. Were people at Elk Ridge the only ones raising domestic turkey flocks? I hope DNA researchers are able to examine more turkeys from other Mimbres villages, including NAN Ranch, to learn about this.

One more way to assess whether people were raising turkeys is by learning what the birds ate. We can study this by examining the signatures of different chemical isotopes in animal bones. Isotopes are atoms of an element with different numbers of neutrons in their nuclei. Luckily for us, the ratio of two carbon isotopes (13C and 12C) in maize is different from the ratio in other plants turkeys would have eaten. Eating plants with different isotopic signatures changes the isotope ratios in an animal’s bones in ways that reflect those differences in diet.

Dolan and colleagues analyzed the carbon isotopes in the turkey bones whose DNA they studied. They found that many turkeys in the Mimbres area were eating primarily maize, including 16 of the 17 turkeys they examined from Elk Ridge. (The sample sizes for the mtDNA and carbon isotope studies aren’t the same, because not every sample yielded enough well-preserved ancient DNA or carbon to give reliable results.) The one tested Elk Ridge turkey that had not been eating maize was also one of the genetically wild turkeys—it’s nice when things occasionally work out the way you’d expect! The mix of genetically wild and domesticated turkeys, and of turkeys that were or weren’t mainly fed by humans, suggests to me that people had a pretty flexible approach to managing their turkey flocks, and to where and how they got the feathers they needed.

Thank you to the people who made some of this research possible, especially Karl Laumbach, the NAN Ranch owners, and Danielle Romero and her tiny but mighty staff at the WNMU Museum. The National Science Foundation (BCS-1524079 and BCS-2312349) supported my work on the Elk Ridge turkeys, and our 2024 field school was supported by generous donors and members of Archaeology Southwest and the Grant County Archaeology Association.

For further reading:

(I’m happy to help you access these if you hit a paywall. Email me at karen@archaeologysouthwest.org.)

Conrad, Cyler

2021 Contextualizing Ancestral Pueblo Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo spp.) Management. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 29:624–665. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-021-09531-9

Dolan, Sean G., Andrew T. Ozga, Karl W. Laumbach, John Krigbaum, Aurelie Manin, Christopher W. Schwartz, Anne C. Stone, and Kelly J. Knudson

2023 Turkey Iconography, Domestication, and Husbandry in the Mimbres Valley, New Mexico, AD 1000-1130. American Antiquity 88:41–61. https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2022.81

Archaeology Southwest Magazine’s recent issue on birds has several articles on turkeys in the Mimbres, Four Corners, and other areas of the Southwest.