- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- In Memoriam: Bill Lipe

Particular to Preserve

The Life and Legacy of William D. Lipe

(April 14, 2025)—In 2014, I attended the annual meeting of the Society for American Archaeology in Austin, Texas, to present a research project for which I’d cooked beans in baskets using the hot-rock method to show it could be done. Among those who swung by my poster was the legendary William “Bill” Lipe, with whom I’d had sporadic email correspondence while attending grad school and exploring the human history of the Bears Ears area of southeastern Utah.

Bill warmed to the fact that I was a former resident of Flagstaff, Arizona, as he’d lived there for many years while working for the Museum of Northern Arizona. He was even more intrigued to learn that I was then working as a seasonal archaeologist for the National Park Service at Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, the place where he’d cut his teeth—and, in some ways, established his legendary reputation—during the 1950s.

But the real surprise came when he suggested I look into the Southwestern archaeology program at a little university in a crumby little city in upstate New York called Binghamton.

Now, I was born and raised in Binghamton. And I hated it. I’d fled as fast as I could the moment I escaped high school, moving to New Orleans for about half a decade before making my way out west and never, ever looking back.

My love of all things wide open and arid had kept me pinned to the western half of the United States until an even greater love drew me to the Grand Canyon, where I also added archaeology and Indigenous cultural preservation to my list of loves, before ultimately attending Northern Arizona University and then the University of Utah—only to wind up meeting Bill Lipe, one of my heroes, and learning that the awful little burg of my birth hosted one of the best programs in public- and conservation-oriented archaeology in the entire country. A program my same hero had overseen from 1964 to 1972.

From this most unlikely of coincidences began a decade and a half of friendship and collaboration that has inexorably shaped the course of my life—something Lipe has done for countless others (read, for example, author Morgan Sjogren’s remembrance).

. . .

Bill Lipe came into the world on May 5, 1935, in the little town of Struggleville, Oklahoma (yes, that’s a real place). He was plagued by severe asthma as a kid, the treatment for which at that time consisted primarily of staying indoors and trying not to move very much. He spent that time reading about explorations of the Southwest’s canyon country, something I also did through the works of Edward Abbey and Ann Zwinger while avoiding the oppressive heat and humidity of New Orleans. Thankfully, Bill largely recovered from his asthma when he was 15.

The Lipe family then made their way to Bristow in 1941, where Bill graduated from high school. In 1953, he commenced his college journey at the University of Tulsa—for journalism, of all things. But it didn’t take long for him to realize that his true love was anthropology (though he remained a prolific writer and correspondent).

Because the University of Tulsa didn’t have an anthropology department, he transferred to the University of Oklahoma, where he finally got a taste of the Southwest when he attended a field school hosted by the University of Arizona in 1956. Bill graduated from OU with a bachelor’s degree in anthropology in 1957, and dove into graduate school at Yale University later that same year.

![Staff and students of the 1956 Point of Pines field school. Bill Lipe is in the back row in the University of Arizona shirt, surrounded by other then- and soon-to-be luminaries of American archaeology. Image © Arizona State Museum, University of Arizona. Emil W. (Emil Walter) Haury, 1904-1992, Staff and students of the 1956 season, [3966_scan1.jpg]. Arizona Memory Project, accessed 14/04/2025, https://azmemory.azlibrary.gov/nodes/view/36993](https://www.archaeologysouthwest.org/wp-content/uploads/Point-of-Pines-1956-Lipe-in-AZ-tee.jpg)

How the dam came about is a tale in its own right, and you can read more about that here.

For this tribute, the thing to know is that, in those days, archaeological research took a backseat to economic development—a situation that is increasingly coming back to life. Limited time and funding meant that only occasional salvage efforts could be made before significant archaeological sites were damaged or destroyed. The first major development project to signal a shift in this attitude was the damming of Glen Canyon, when the National Park Service directed teams of archaeologists from the University of Utah and the Museum of Northern Arizona—under the direction of Utah’s Jesse D. Jennings, a notoriously fiery fellow—to conduct salvage archaeology in the projected lake corridor and beyond. In fact, in a letter to the University of Utah, the Park Service stipulated the following:

You should not concern yourself only with the land which will actually be flooded… I believe you should instruct your [crew chiefs] to look over all the lands adjacent to the canyon which give promise of being of importance in any field of investigation. We are very anxious to know just what archeological, historical, and biological resources exist in the Glen Canyon region.

Bill was one of those crew chiefs.

His work in Glen Canyon was part of the largest salvage archaeology project in the US, running from 1957 to 1963. Archaeologists documented more than 2,000 sites during this period, and crews excavated some 200 more to gather people’s belongings and record where they lived.

His four years of surveying and excavation established a detailed archaeological record of the area’s Pueblo history, though he acknowledged that much evidence remained untouched. This experience influenced his belief in a conservation-first approach to archaeology and sparked his long career in archaeological study, preservation, and public education.

“Over the years, my work has been driven by a personal conviction that archaeological sites are finite, nonrenewable resources that are valuable to society,” Lipe said to his colleagues at Washington State University, when reflecting on his time in Glen Canyon. “Like natural resources, they require stewardship and management for future generations.”

. . .

On February 17, 1962—about a year before the end of the Glen Canyon Project—Bill tied the knot with the lovely June Finley, with whom he would father three children: Carrie, Jessica, and David. Two years later, he started work as an Assistant and then Associate Professor at the State University of New York in Binghamton—now Binghamton University.

Bill got his Ph.D. from Yale in 1966, focusing his dissertation on the results of his work on the Glen Canyon Project. He then headed straight back to the region with his friend and colleague R. G. Matson, to begin exploring and documenting a little-known area immediately to the east: Cedar Mesa.

The area had come to his attention during the Glen Canyon work, and—because the Park Service had so generously said not to concern themselves “only with the land which will actually be flooded” ten years earlier—Bill pivoted his focus to this archaeological wonderland once described by archaeologist Nels Nelson as “tortuous and fantastic.”

Thus began the Cedar Mesa Project, which ran from 1967 to 1975. Bill undertook an initial reconnaissance survey while he was still a professor at Binghamton University, using a small faculty-research grant. The scope was Cedar Mesa itself and parts of Elk Ridge, Dark Canyon, and Fable Valley. This initial foray included minimal documentation and mapping and no collections—a quick-and-dirty look at the region for the ostensive purpose of locating sites previously excavated by Richard Wetherill and to hopefully expand knowledge of the Basketmaker II culture period (ca. 1500 BCE to CE 500 in the Bears Ears region).

Subsequent surveys beginning in 1969 took in much more of the deep canyons of Cedar Mesa, most notably Grand Gulch. Bill and R. G.’s research design expanded to include explorations of post-Basketmaker II settlement systems—and to relocate more of the sites visited by Wetherill and other early figures, a process that continues to this day.

These survey efforts had two objectives: First, a thorough look at an area framed by Sheiks Canyon, Coyote Canyon, and the Grand Gulch rim, as well as the section of the road that stretches from the Coyote drainage over to the Sheiks drainage. They also poked around a few spots between Sheiks and Bullet Canyons, a bit to the south.

Second, a focus on Grand Gulch, mainly between the mouth of Kane Gulch and a bit downstream from Sheiks Canyon—plus a section that went a little upstream and downstream from Collins Spring Canyon. They leaned on notes from Richard Wetherill’s 1896–97 work and Nels Nelson’s surveys from the 1920s. They had some success at this, although it would be superseded in the 2000s by the Reverse Archaeology project spearheaded by Fred Blackburn and Winston Hurst.

Excavations followed, as was the custom at the time. The work focused on the mesa-top sites. Most of them were Basketmaker II sites, although Lipe and team also conducted test excavations in at least one site dating to Pueblo II (900–1150 CE) or Pueblo III (1150–1290 CE) that showed potters were firing in kilns.

What Lipe and Matson call the Cedar Mesa Project Proper launched a year later, in 1972, with intensive quadrat surveys throughout the greater Cedar Mesa area. By that point, Bill had left Binghamton to take up a position as Assistant Director of the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff. R.G. Matson was then an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia. They conducted their three-year intensive archaeological investigation with support from the National Science Foundation, and the resulting dataset forms the basis of Cedar Mesa research and preservation efforts to this day.

The work was done out of a camp established at the head of Todie Canyon, where Bill’s wife and children were often found helping out around camp or playing in piles of excavation backdirt. Their tent camp was set up near a good spring where the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) had previously installed a pipe to collect water, and they installed their own water tank beneath it to catch water. They called the place Todie Camp, and their crew the Leper Colony. Bill once told me about one of the camp cooks, an intense fellow who made delicious food—and, it turned out, had taken the gig in order to hide from authorities who wanted to chat with him about a murder.

A number of ancillary or “satellite” projects also accompanied the Cedar Mesa Project, including a clean-up effort in Grand Gulch in 1974 under field director Don Keller—who now also lives in Flagstaff. What these folks were cleaning up was, in effect, detritus from excavations conducted by Wetherill and others in the 1890s. This project was done at the behest of the BLM, which believed the leavings incentivized looters to sink their own shovels in.

In 1976, Bill served as principal investigator—with Richard Ahlstrom as field director and Matson doing a lot of legwork of his own—on an inventory of two major tributary drainages of Grand Gulch. This project anticipated creation of the Grand Gulch Primitive Area, a protective measure that was also likely to attract additional recreation. Grand Gulch remains a Primitive Area to this day, having therefore an even greater level of protection than most of the rest of the lands within Bears Ears National Monument, outmatched only by the Dark Canyon Wilderness Area to the north.

After that, Bill served as Director of Research at Crow Canyon Archaeological Center in Cortez, Colorado, from 1985 to 1993. He oversaw studies of Pueblo settlement patterns, community organization, and sociocultural shifts in the Northern San Juan region. He also joined the faculty at Washington State University (WSU) in 1976, where he remained until his retirement in 2006—the same year I began my own studies in Southwest archaeology in his former hometown in northern Arizona and one year after the passing of his beloved wife June.

Between these episodes, he held the prestigious position of President of the Society for American Archaeology (SAA) from 1995 to 1997. He also received several well-deserved accolades, including the WSU College of Liberal Arts Distinguished Faculty Achievement Award in 1997, the John F. Seiberling Award from the Society of Professional Archaeologists in 1998, the SAA Distinguished Service Award in 2000, and the A.V. Kidder Award from the American Anthropological Association in 2010. Most recently, he received recognition as a Distinguished Alumnus from the Dodge Family College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Oklahoma in 2023.

. . .

Getting back to Cedar Mesa—and here we’re going deep, stay with me to understand even more about this man’s legacy—efforts to create elevated legislative protection for the immense assemblage of material heritage in the area date back to at least 1904, when Edgar Lee Hewett recommended the Bluff District be protected alongside the Chaco District, Pajarita Plateau, and other cultural landscapes. It was almost part of an enormous early version of Escalante National Monument in the 1930s, but that effort got derailed by World War II. Robert F. Kennedy also attempted to take up the cause during his presidential campaign, and spoke with members of Tribes in the region about this and other issues as part of his presidential campaign. Kennedy vocalized his private anger in public forums. In 1967, he persuaded his fellow senators to create a subcommittee on Indian education and name him as its chairman. Unfortunately, Kennedy was assassinated before the election, and the pro-Indigenous fervor he attempted to foment in Washington, DC, went with him.

Proposals to help better protect the place simmered along for the next several decades, but—apart from the designation of Grand Gulch as a Primitive Area with help from Lipe and his colleagues—nothing really came of it until 2010. That was the year Bluff-based Friends of Cedar Mesa (now the Bears Ears Partnership) was founded as a 501(c)(3) conservation organization by former BLM ranger Mark Meloy, partly out of a desire to honor the place so beloved by his late wife, celebrated author Ellen Meloy. Bill Lipe got involved with the organization almost immediately, presenting a fun retrospective on the Cedar Mesa Project at their first public event in June of that same year.

These efforts increased in proportion to the increasing visitation in the greater Cedar Mesa or “Bears Ears” area, so-called because of the two sandstone monadnocks that sit atop Elk Ridge just to the north of Cedar Mesa. It was also in 2010 that late Senator Bob Bennett initiated a land-use planning initiative in San Juan and a few other counties under the auspices of a collaborative negotiation process with interested parties. Bennett asked Native people in San Juan County if they had any interest in how public lands were managed.

I don’t know what answer he expected, other than, “Uh, yes?!”

Which is about how the Utah Tribal Leaders Association responded in March of that year. They requested “full engagement and consultation with local and regional tribes in county-by-county land use planning and legislative processes…” so long as the process provided early, honest, and transparent consideration of the rights and interests of individual Tribes. This represented the response by Tribal leaders of the Navajo Nation, Skull Valley Band of Goshutes, Paiute Tribe of Utah, Uinta/Ouray Ute Tribe, NW Band of the Shoshone Nation, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe (including White Mesa), and the Confederated Goshute Tribe.

Out of this initiative came Utah Diné Bikéyah, which means approximately “Sacred Navajo Homeland [of/within] Utah.” They spent several years canvassing Tribal elders and stakeholders for their input, synthesizing and mapping the results. They were initially a project funded by Round River Conservation Studies, but broke away with their own 501(c)(3) filing in 2014.

Meanwhile, that same fateful year, Friends of Cedar Mesa submitted their own proposal for a Greater Cedar Mesa Conservation Area based largely on input from—you guessed it—Bill Lipe. To supplement this effort, and to help generate public interest and support, Bill took the reins as guest editor of an issue of Archaeology Southwest Magazine focused on Cedar Mesa, titled Tortuous and Fantastic: Cultural and Natural Wonders of Greater Cedar Mesa (the title being borrowed from Nels Nelson’s description of the place almost a century earlier). Local publication Blue Mountain Shadows also did an issue on Cedar Mesa that fall.

The two conservation campaigns, along with several others, converged in 2015 with the newly formed Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition leading the effort. Crow Canyon Archaeological Center threw their own hat into the ring later that year with a letter signed by 120 archaeologists calling for the protection of the greater Cedar Mesa area, capped off with the following quote by none other than Bill Lipe:

It is time to recognize the Bears Ears area for the national treasure that it is. The Bears Ears area has great potential for future archaeological research, as well as for productive collaborations between scientific researchers and Native American groups.

This is also when our respective realms reconverged in a major way. I’d been exploring the Cedar Mesa area since 2006, when I moved to Flagstaff to begin studying archaeology, and had shifted over to academically studying it starting in 2012 when I arrived in grad school. I also worked as a seasonal archaeologist in Glen Canyon National Recreation Area from 2010 to 2013, and in 2014 began working as an archaeologist for the Manti-La Sal National Forest—the footprint of which comprises the central one-third of the subsequent national monument.

I was first tasked with writing a Class I report—technical jargon for a synthesis of all the existing literature one can beg, borrow, or steal—for the area for SWCA Environmental Consultants on behalf of the BLM starting in 2015, and was then hired by former Utah State Archaeologist Kevin Jones to help draft a report on the archaeological significance of the area on behalf of Utah Diné Bikéyah. A year later, I was back in Bears Ears working for the Forest Service and conducting research on behalf of the increasing national monument push, and my involvement only escalated from there.

After the monument was first proclaimed by President Barack Obama in 2016, following the election of Donald Trump for his first term, efforts refocused toward protecting the monument from the inevitable attacks that would ensue. To that end, Archaeology Southwest and Friends of Cedar Mesa convened an Experts’ Meeting in Bluff in the summer of 2017 to combine broad-scale, non-specific information about settlement history in the area in order to generate both a public report and a more detailed lawyers’ report.

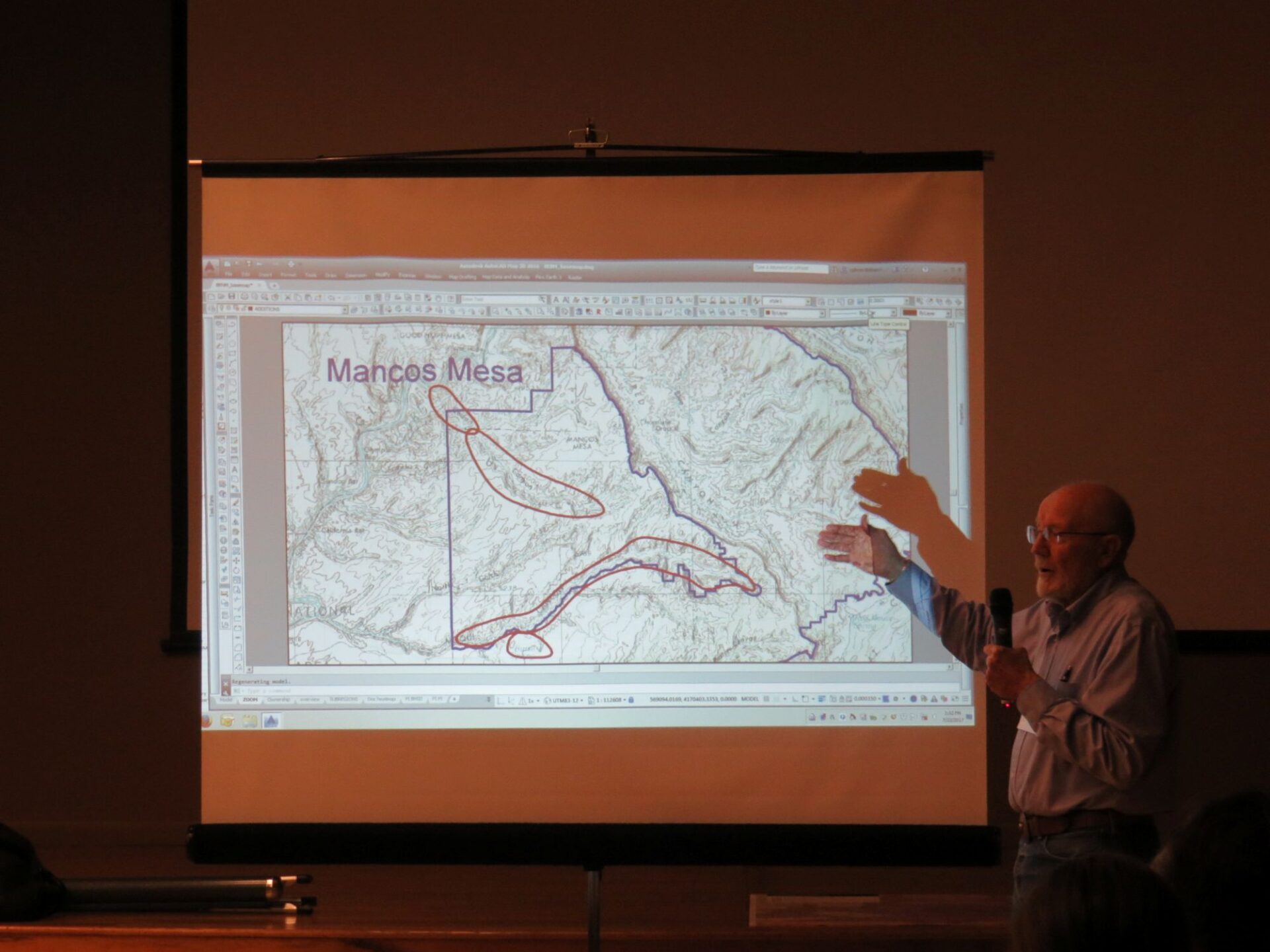

And what a meeting it was! Bill Lipe and R.G. Matson were both in attendance, along with their former crew member Don Keller; local research luminaries Winston Hurst, Jonathan Till, Lee Bennett, and Fred Blackburn; conservation leaders Josh Ewing and Vaugh Hadenfeldt; top-tier academics like Jim Allison, Laurie Webster, and Sally Cole; lower-tier researchers and advocates like myself, Ben Bellorado, Jim Krehbiel, Natalie Cunningham; and federal agency archaeologists Don Simonis, Don Irwin, and Leigh Grench. Even private-sector cultural resource management was represented there, specifically in the form of SWCA, which sponsored my own attendance.

Over beers and barbecue afterward, Fred Blackburn instructed me to take as many photos as I could: “You will never see a gathering like this one again in your life.”

Out of that meeting came the previously mentioned reports, as well as another issue of Archaeology Southwest Magazine, this time with myself and Ben Bellorado as the guest editors. Sacred and Threatened: The Cultural Landscapes of Greater Bears Ears hit shelves half a year later, the largest issue of the magazine published to that point, with Bill Lipe providing the introductory overview of Bears Ears cultural history and co-authorship on a summary of what was supposed to be my dissertation.

Two years after that, with a lot of encouragement and coaching from Bill, all the years of gathering and crunching research that I’d done for the Class I, the Utah Diné Bikéyah proposal, the experts’ and lawyers’ reports, and the magazine, I published a mainstream book about the place and its history that nabbed an Editor’s Choice Award from ForeWord Book Reviews.

I quote, cite, or refer to Bill in that book exactly 41 times, and the book is 410 pages long, so on average about once every ten pages.

. . .

There is no way to really quantify the legacy and impact of a man like him. His 1974 publication “A Conservation Model for Archaeology,” in which he called the archaeological record a “non-renewable resource” and pleaded for “slowing down the attrition of the resource base,” would be enough on its own. He authored or co-authored no fewer than 150 publications, and at least as many presentations and papers read at various conferences and other venues. In fact, there’s even a book about him called Tracking Ancient Footsteps: William D. Lipe’s Contributions to Southwestern Prehistory and Public Archaeology, edited by his good friends and colleagues R. G. Matson and Timothy A. Kohler.

In an updated version of his famous Conservation Model that he wrote on behalf of Archaeology Southwest, Bill laments how we “now realize that all sites are rather immediately threatened, if one takes a time frame of more than a few years. In this sense, all of our archaeological efforts are essentially ‘salvage.’ I submit that we not only need to know how to do ‘salvage’ archaeology, but also how not to do it. The latter involves creating a model of resource conservation.”

He then goes on to explain how the most important ways to achieve the goal of archaeological conservation are minimization of destruction by seeking non-destructive research methods, establishment of archaeological preserves and other areas of elevated legislative protection—so: places like Bears Ears National Monument—and, most importantly, public education. If people don’t know a thing is worth protecting, they won’t lift a finger to protect it.

This last lesson is the one he imparted upon me the hardest, informing pretty much all of my subsequent work—from books and magazine articles, to public talks at archaeological societies and schools, to interpretive guided hikes in areas throughout the greater Southwest. Bill was a great believer that nothing gets done without having the public on your side, and you can’t get the public on your side if you talk over their head with jargon, or talk at them with officiousness and regulatory recalcitrance, or leave them out of the talking process entirely. You have to talk to the public. It’s the only hope we’ve got.

The last time Bill and I hung out was on March 9, 2020, at the Celebrate Bears Ears event in Bluff, where Bill had come to take part in a panel discussion and give some remarks on the area. That was a mere six days before states began implementing shutdowns to slow the spread of the COVID-19 virus. Bill was 85 years old at the time, and his doctor had strongly suggested that he stop all this flying-across-the-country stuff even before the pandemic erupted, but there he was. Engaging with the public as always—and then meeting up for some wine and reminiscences with myself and some like-minded others afterward.

Among other topics, we talked about a quote by Richard Wetherill’s father Benjamin Kite that had recently resurfaced thanks to historian Harvey Leake: “We are particular to preserve the buildings, but fear, unless the Gov’t sees proper to make a national park of the Cañons, including Mesa Verde, that the tourists will destroy them.” Bill laughed at the irony between sips of chardonnay, musing how differently Southwest archaeology might have gone if old B.K. had published his letter pleading for the protection of Mesa Verde in a newspaper or magazine instead of mailing it to the Smithsonian for William Henry Holmes to ignore.

That’s how I will remember him: An unstoppable force whose inertia will carry on indefinitely. Bill Lipe, a staunch and celebrated academic to the end, believed in the power of everyday people to help safeguard the fragile and irreplaceable material heritage interwoven within the lands of the Southwest and beyond.