- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Inclusion and Exclusion

|

By Jeff Clark, Preservation Archaeologist

|

After spending more than twenty years scrutinizing the Salado in nearly every valley and basin in the southern part of the American Southwest, it’s time for us to step back, think deep thoughts, and hopefully come up with some profound conclusions—maybe even some with modern relevance.

We believe that the Salado included both Kayenta immigrant minority and local majority populations from a variety of backgrounds. These culturally diverse groups lived in close proximity for more than a century while maintaining some aspects of their identity and cultural traditions. Reconstructing how these groups interacted is essential to understanding the Salado.

As we synthesize diverse data sets, we are finding several concepts useful for understanding and describing what happened: coalescence, diaspora, otherness, and ideologies of exclusion and inclusion. The last two terms are perhaps the most difficult to grasp, particularly since we are defining these ideologies based on ancient ceramic styles that have little meaning to archaeologists, except as markers of time.

Ideologies of exclusion unify people by setting up oppositions with other similarly defined groups or even large organizations, such as states. Membership is generally restricted and based on just about anything that can be used to categorize people: descent, ethnicity, race, language, culture, religion, or any combination of these. A group defined by an exclusionary ideology cannot exist without an Other, a competing group that is viewed monolithically, and often in negative terms.

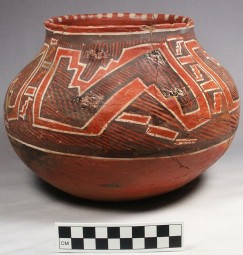

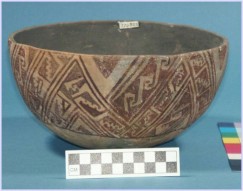

We have argued that when Kayenta immigrants first moved into the southern U.S. Southwest in the late A.D. 1200s, there was an initial period of tension with local majorities. Both immigrant and local groups moved into defensible settlements and overtly displayed their identities on the designs they painted on their ceramics. In the San Pedro Valley, Kayenta immigrants made Maverick Mountain series pottery (Image 1) similar to the ceramics they had made in their homeland. In response, local groups revived their own ceramic tradition, making San Carlos Red-on-brown (Image 2). Based on distribution patterns, neither group particularly liked the pottery of the other.

We believe that, during this interval, both groups were practicing exclusionary ideologies, pitting local against immigrant. Although these two pottery styles may have evoked strong emotions among the ancient inhabitants of the southern Southwest, they have little more than aesthetic and scientific value to you and me. A meaningful analogue might be the Star of David and crescent moon in Southwest Asia. We all know the power of these symbols with respect to group identity within their respective communities, and the tension that exists between these communities. To the uninformed archaeologist, however, only their high frequency of occurrence on objects recovered from domestic and religious contexts would reveal their importance as symbols of group identity. The near-exclusive distributions of both images and their correlation with fortified boundaries would suggest that the two groups had an antagonistic relationship.

Ideologies of inclusion, on the other hand, unify people by creating new identities that are larger than existing identities. Membership is generally open to anyone who adopts the basic tenets of the ideology, which are based on action rather than ancestry. These new identities supersede but do not replace previous identities, including those based on exclusionary ideologies. Inclusive ideologies can be expected to emerge in places where there is long-term and frequent contact between groups of different cultural backgrounds. These ideologies are often religious in character, but can also be cultural (e.g., the American Dream). Indeed, religion can be either a powerful integrator or divider, depending on the context.

Building on Dr. Patricia Crown’s work, we believe that the Salado was an inclusive ideology. After a generation of two of close interaction, immigrant-local barriers in the southern Southwest began to break down. The Salado may have been a new religion that both immigrants and locals could join while retaining aspects of their old identities. Intriguingly, this religion seems to have developed initially among the immigrant minority and their descendants. It then spread rapidly to local groups in densely populated areas. The religion was expressed primarily on Salado polychrome vessels that became widely used across the southern Southwest by A.D. 1350, replacing earlier divisive ceramic traditions. The high frequency of horned and plumed serpent motifs on Salado polychrome pottery (Image 3) has been noted by Crown and other scholars. This motif may be an important clue about why the Salado religion appealed to both local and immigrant groups, as it is associated with Quetzalcoatl, a powerful deity in the pantheons of more complex Mesoamerican societies.

Salado polychromes have only aesthetic (and, unfortunately, economic) value in our modern society. When viewed by the ancient inhabitants of the southern Southwest, however, images on these vessels may have promoted an ideal of unity that transcended previous cultural differences, such as that depicted by this image (Image 4) or the popular “COEXIST” bumper sticker. Determining the extent to which this ideal was realized is critical to understanding the success and failure of the Salado.

2 thoughts on “Inclusion and Exclusion”

Comments are closed.

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.

I hate to be a dope, but why is bowl in figure 3 said to have “plumed serpent imagery?” I don’t see plumes or serpents on it.

A good question that I will try to answer.

I count about 14 design motifs on the interior and six on the exterior that have been interpreted as the heads of plumed or horned serpents. The heads are profile views and I think you can easily discern the square eyes. The triangles containing the eyes are heads and the plumes or horns are the appendages on top of the triangles. The best examples of plumes are on the interior-they almost look like quail heads. The other appendages are “F”-shaped that could be plumes or horns. The best evidence on this vessle that these are serpents are the long bodies and possible scales on the exterior motifs.

There is always a high degree of subjectivity in interpreting design motifs on pottery and rock art, especially stylized examples such as these. However, these images are all over Salado polychromes and other late pre-contact pottery. They include examples with elongated bodies that are more serpent-like than those depicted here. Ethnographic evidence about Puebloan religion lends further support to the serpent interpretation and association with Quetzecoatl.