- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- From Durango to Durango and Las Vegas to Las Vegas...

Several of Archaeology Southwest’s staff members attended the 14th biennial Southwest Symposium at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, held from January 9 to 11. Because it focuses on current research in the Southwest, this conference is one of my favorites. This year’s theme was “Social Networks in the Southwest,” so the forum included papers and posters on a variety of topics revolving around interaction and social boundaries (including two papers by authors from Archaeology Southwest).

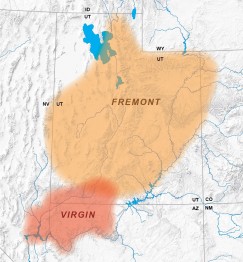

As is often the case, there was also a special session dedicated to the archaeology of the host region—this time, the archaeological regions typically known as the Fremont and Virgin Branch Pueblo (formerly “Virgin Anasazi”) culture areas. This session was particularly interesting to me because I don’t know much about those areas. In this and a subsequent blog entry, I’ll share a bit about what I learned, thereby adding these areas to my earlier series on archaeological culture areas in the Southwest.

A New-Old Definition of the Southwest

The title of this blog entry echoes an oft-repeated definition of the Southwest coined by Erik K. Reed, who in 1964 defined the Southwest as ranging from Durango, Colorado, to Durango, Mexico, and from Las Vegas, New Mexico, to Las Vegas, Nevada. Catchy—and that may be one reason why it has had such lasting impact. Reed did define a “greater Southwest” that was a bit more inclusive, however:

The archaeological Southwest extends approximately from Durango, Colorado to Durango, Mexico and from Las Vegas, New Mexico to Las Vegas Nevada, and from the Pecos River to the lower Colorado River and central Utah. The term “greater Southwest” includes the intermontane arid region south of about Great Salt Lake, as well as the deserts of southern California and Baja California.

Whenever people repeat this definition, they usually leave out the part about central Utah and southern California. (Not quite catchy enough?) Scholars certainly considered those areas relevant to Southwestern archaeology in the early twentieth century. In the very first synthesis of Southwestern archaeology in 1924, A.V. Kidder included the eastern half of the Great Basin north to the Salt Lake as “the northern peripheral district” of the Southwest.

Since the 1970s and 1980s, however, archaeology in these regions has become more closely linked to research on foraging and hunting groups farther north and west. For a number of reasons, the questions asked by archaeologists working in the Great Basin have diverged from those asked by archaeologists working elsewhere in the Southwest. The former tend to focus on modeling subsistence and behavior, and cultural explanations for change are not favored. I was pleased that several presentations called for a reintegration of the eastern Great Basin with the archaeology of the Southwest.

The Fremont Region

Much of central and northern Utah falls within an archaeological culture area archaeologists call the Fremont region. People living in the major river valleys of the vast Fremont region were farmers who also hunted and foraged. Early Fremont dwellings were typically circular semisubterranean pithouses with central hearths and roof entrances. Around A.D. 900, people began building rectangular pithouses. Archaeologists have also documented surface rooms constructed of adobe and sometimes masonry that date still later in time. Some structures include multiple adjacent rooms, similar to pueblos further south. Often, aboveground rooms are also associated with large, typically rectangular constructions—called “central structures” by some archaeologists—where public activities probably took place.

Fremont potters created black-on-white and black-on-gray pottery. They decorated these with their own painted design styles and with designs similar to Ancestral Pueblo ceramics. They also produced textured cooking and storage pots, many with interesting appliqué features and surface treatments. Indeed, people living in the region developed a distinctive art style, which they expressed in incredible rock art and beautiful figurines, as well as in particular styles of baskets, moccasins, and ground stone.

[tn3gallery id=38 size=narrow]

(Hold your cursor over each image of Fremont material culture to view Scott Ure’s captions.)

As several of the papers in this session suggested, social changes and developments in the Fremont region were closely tied to broader regional trends that also affected the Ancestral Pueblo Southwest and beyond. In particular, several researchers noted that the expansion of Fremont populations north into Utah toward the Great Salt Lake coincided with the spread of Chacoan influence into southeast Utah. Is it possible that people were being forced out or were deliberately moving away from Chaco’s reach? An interesting paper by Scott Ortman used linguistic and archaeological data to explore the possible historical connections between the Fremont region and the Kiowa-speaking communities that were residing on the southern plains by the nineteenth century. Ortman suggests that some Fremont communities may have included Kiowa speakers, and that Fremont people and certain Ancestral Pueblo populations may have shared common heritage (Kiowa and Tanoan, a contemporary Pueblo language family, derive from a common linguistic root).

These large-scale analyses really highlight the kinds of new insights we might gain if we reevaluate the old regional boundaries that have structured research for so long. Durango to Durango and Las Vegas to Las Vegas is starting to feel much too small. In my next post, I’ll share information about the Virgin River area.

Special thanks to my colleague Scott Ure (Brigham Young University) for compiling the slideshow of Fremont images in this post, and for his comments and clarifications on a draft of this post.

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.