- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Something There is That Doesn’t Love a (Painted)...

(With a nod to poet Robert Frost!)

It’s always fun introducing new site stewards to a site, especially on field trips with experienced site stewards. Nanette Weaver and Bob Sherman, the new regional site steward coordinators for the lower and middle San Pedro River area, have been promoting tours of sites with site stewards to introduce new folks to the team and to encourage everyone to share their experiences.

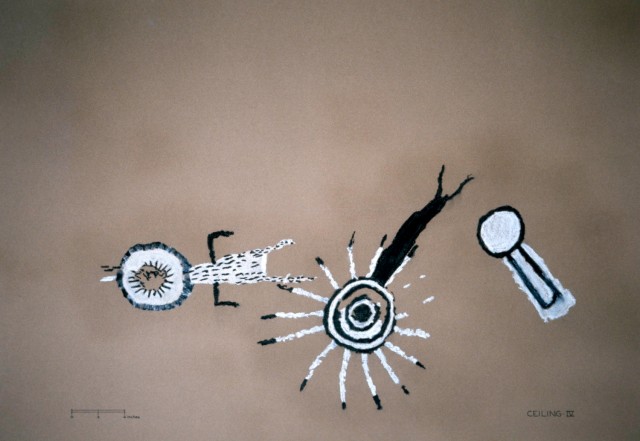

Last week, we visited a rockshelter located on Arizona State Trust land. The site has a spectacular set of Apache pictographs painted on the walls and ceiling. In 1975, Pat Vivian (then of the Arizona State Museum [ASM]) and Polly Schaafsma produced a technical report on the site for the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). They documented the pictographs with slide photography, and then they projected the slides onto paper, tracing the images. They painted the tracings with pastels that were color matched to the images on the slide.

I obtained copies of these reproductions from ASM and we took them into the field for the visit. At the site, I gave each steward one of the line drawings and asked them to “find” the images on the walls and ceilings. Some were easy to spot, but a few took a concerted effort to locate. In the end, we were able to relocate 22 of the 25 individual elements based on the drawings. The three “missing” elements located on two separate wall panels may have been destroyed: parts of the walls and ceiling of the rockshelter have collapsed since the 1975 recording project.

Comparing the pictographs as we saw them that day with the documentation of what they looked like almost 40 years ago raised several interesting questions. In the late 1980s, the site was conveyed to the State by the BLM as part of a series of large BLM–State of Arizona land exchanges. One such exchange allowed BLM to acquire many of the lands at Perry Mesa that are now within Agua Fria National Monument. When the exchange occurred, it was decided that the site should be fenced in order to protect it. A heavy storm fence topped with barbed wire still surrounds the site, but the gated entrance is unlocked. At the western end of the fenced area, a portion of the rockshelter’s ceiling collapsed on the fence, requiring the fence to be relocated. One of the panels we couldn’t find was in the area now covered by the fallen ceiling. I can’t help but wonder if the fence installation contributed to some of the wall fall.

Despite the best of intentions to protect the site, hundreds of inscriptions in the soft sandstone of the rockshelter (most of which were not in the areas where the pictographs are found) demonstrate that the shelter is a popular spot with many local people. Most of the visitors are probably young people—my wife and I no longer express our undying love for each other in stone (and, truth be told, haven’t for many, many years), so I suspect that most of the inscriptions smelled like teen spirit.

In retrospect, a heavy fence, abruptly installed without any consultation with local residents, may not have been the best strategy to engender a sense of respect. Not exactly a case of “good fences make good neighbors.” We wondered if the fence inadvertently contributed to some of the vandalism to the paintings themselves, by sending the obvious message that local people couldn’t be trusted. Fence is to male teenager as red flag is to bull!

A further disheartening observation—at least from our non-Apache point of view—is that natural weathering is playing an even more destructive role. Vivien and Schaafsma noted this almost 40 years ago. Seeing these paintings in person is stunning; rendered in five colors, the images are striking. In a generation, the ability to experience the magic of this place will be gone. Although the rock art has been carefully documented, and that’s a good thing, looking at a photograph or painting in a lab will never replace the enchantment of being present in the shelter.

This site is one of only a handful of known Western Apache rock art sites in Arizona. One of equal note located in the low hills north of Willcox is reported to be buried beneath a wall of graffiti. Does it make sense to take aggressive steps to slow the rate of natural deterioration? Is it even possible without running the risk that the “cure” may accelerate the loss? More importantly, what would Apache people think of preservation efforts that required more invasive techniques? For many descendant communities, the natural deterioration of archaeological sites is part of the natural order; attempts to “preserve” sites are, in a sense, unnatural and undesirable acts.

Upon reading a draft of this post, my colleague Kate noted that it put her in mind of certain lines from Robert Frost’s poem “Mending Wall”, and I have to agree:

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it,

And spills the upper boulders in the sun;

And makes gaps even two can pass abreast.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Before I built a wall I’d ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

And to whom I was like to give offense.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.