- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- The Quest to the O. W. Randall Rock

When I was in college, I became interested in our family history. I vividly recall one conversation with my paternal grandfather, whom we called “Daddy Jack.” One evening at their home in the piney woods around Nacogdoches, Texas, I asked him to tell me what he knew about the Randall family. Little did I realize that he knew a great deal, and he began to recount the story of his father, then his grandfather, then his great-grandfather. He knew their names, the names of their wives, many of their children (his uncles and great-uncles), and various tales about their lives. But it was the story of his great-grandfather that was the most intriguing of all.

This man was Osborn Woods Randall, who was always known as “O. W.” My grandfather began the tale: O. W. was born in New England but came to Texas as a young man, passing through Tennessee. He settled in Nacogdoches, fought in the Texas War of Independence from Mexico, and was awarded land in that county. Like many of his day, he dreamed of striking it rich in the 1849 Gold Rush, so he traveled to California. He was one of the lucky ones, my grandfather said, and returned to Texas with two tin cans filled with gold nuggets. But on his return, he was chased by robbers, and rode home “fast as lightning” and immediately buried the tin cans in a peach orchard.

As I heard this tale, my skepticism must have shown on my face, for my grandfather then went on to give his own substantiation to the claim of O. W.’s gold discovery. He recounted that, when they were young, he and his brother Jesse discovered a gold nugget wedged between a hog’s teeth while they were slaughtering it! Now, this caused considerable excitement at the time (and with me!), but no one had any idea where the hog might have rooted out that gold nugget, and no one knew where O. W.’s peach orchard might have been.

I remained a bit dubious of his trip to California, his discovery of gold, and his return with cans of gold nuggets. But when exploring our history a few years later, I read in Adolphus Sterne’s diary of Nacogdoches that O. W. Randall had “returned from California last night”! The date of that diary entry was August 1, 1851. So, the story must be true—not that I really doubted my grandfather’s account, but I realized that family stories are often exaggerated through the years.

Little new information came along, until a group led by Rose Ann Tompkins was exploring the Southern Emigrant Trail along the Gila River. On October 30, 2003, in an unnamed canyon near the Oatman massacre site, her fellow explorer, Tracy DeVault, saw petroglyphs and then an inscription on a boulder: “O. W. Randall 1849.” Such an inscription was unusual, because it included his surname and date (other inscriptions have only initials). They published this finding in their diary and wondered if they might “just find something on O. W. Randall 1849.” Dave Stanton also explored this canyon and realized that O. W. was probably from Texas, as he had used this southern trail. Dave searched the Internet for information and discovered records of an O. W. Randall in Nacogdoches, Texas. Not satisfied with this general information, Dave then contacted the county office in Nacogdoches, inquiring if any of O. W. Randall’s descendants might still live in the area. Indeed, my uncle did (on the original O. W. Randall land grant, in fact). Photos and emails were exchanged, and talk was made about visiting the site. Unfortunately, my uncle Javan and his son, Rick, died in the next few years, and the idea languished.

Earlier this year, the idea of visiting the O. W. rock resurfaced—partly stimulated by the realization of the uncertainties and brevity of life. I still had all the materials that Dave had sent to us detailing the location of the rock. And when I searched for the rock on the Internet, Archeology Southwest had a photo in their album. That led to new emails and phone calls to Dave and to Archeology Southwest, and establishing contact with Rose Ann Tomkins. My brother, Perry, and I decided we simply must go see this rock, and we persuaded my father, Tom, to go, too. My two sons, Regis and Trevor, required no persuasion at all—they were anxious to go at the first mention of the idea, and are always ready for an adventure.

And so, my dad, my brother, and I flew to Phoenix. My sons drove from Berkeley, California. We met in the town of Gila Bend and arranged to meet with Dave and Rose Ann the following day so that they could guide us to the rock. Rain was forecast (rain in the desert!), so we weren’t sure what difficulties this might cause. After we gobbled our breakfast, we drove about 30 miles on Interstate 8, then turned off onto a dirt road across the desert. This road grade is actually lower than the surrounding desert, so it retained the previous night’s rain. Some of the water was quite deep for my two-wheel-drive rental SUV, and so we slipped and plowed through the water and mud, drove off-road to avoid the deeper water, and even had to be towed through a particularly deep pool.

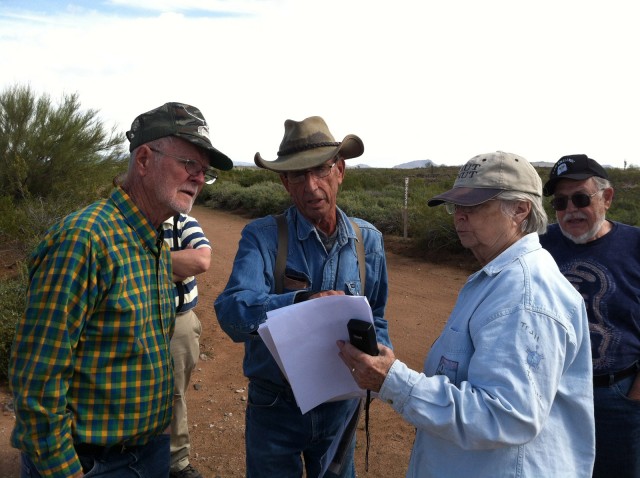

This part of the trip took quite a while, but we arrived safely at the Oatman massacre sight, where Rose Ann and Dave explained the difficulties of crossing this unwelcoming desert as a European American—searing heat, rocky paths, and the back-breaking work of pushing the wagons up a so-called road. It is very sobering to sense how much pain and sorrow and hope is strewn along this trail.

Nearby is a small depression, or “wash-out,” which begins the canyon that ultimately leads to the Gila River. As we hiked down the canyon, over boulders and small pools of water, our anticipation became extreme. Had we travelled so far simply to see a rock in the desert? Yet there it was! Near a deeper pool of stagnant water overgrown with algae, and near small depressions in the rock where Native Americans had ground their corn, about halfway up the west side of the canyon was a large black boulder inscribed with the name of my great-great-great grandfather some 165 years ago: “O. W. Randall 1849.”

Then the unanswerable questions flooded in: What was he doing here in this canyon? Why does the inscription appear almost as a tombstone? What was O. W. thinking and hoping and struggling to overcome? Could he have possibly dreamed that his descendants would one day return to this site—by automobile and airplane? Did he simply want to ensure his quest would not be forgotten?

It was a peculiar time of joy and reflection. It is difficult for us to explain our many thoughts and emotions.

Shortly thereafter, Dave and Rose Ann needed to return home. How could we thank these folks who had driven 1 ½ hours to Gila Bend to meet us—whom they had never met before! And then to spend the whole day with us, making certain we found that rock. Our gratitude was immense and can never be properly expressed.

That night, we five Randall men camped in the desert. Around the tasks of setting up camp, sitting around the fire, eating very good food cooked by my sons, listening to the thunder and avoiding the intermittent rain, hearing bird calls and distant coyotes, each of us wondered: Was this what it was like for O. W.? Would we have had the fortitude to undertake such an adventure?

We had also discovered that O. W. had returned to Texas by ship. He traveled through Panama and sailed with the steamship Falcon to New Orleans, landing on July 11, 1851, arriving in Nacogdoches about three weeks later. We realized that he must have made substantial money in California to take such a trip—so he did, in fact, discover gold, or, as Dave Stanton surmised, maybe he “mined the miners”!

A friend of mine once commented that there is an important distinction between an adventure and a quest. An adventure is done just for the experience and thrill of it. In a quest, however, you seek to be changed. And so, I know each of us has been changed—by the kindness and generosity of our guides, by the austerity of the desert, by the realization that one of our own had traveled on so great a quest.

May we all be so bold.

7 thoughts on “The Quest to the O. W. Randall Rock”

Comments are closed.

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.

THAT, is a great story.

Very cool. It does raise an important issue among the preservation community, however: When does graffiti become “history.” Preservationists currently work to avoid all “imitation” petroglyphs and “Kilroy was here” carvings. Will descendants in 100 years have a similar story to tell?

Bruce, your comment puts me in mind of Inscription Rock at El Morro…

O.W. seems to be quite a strong man and adventurer. It is never too late to see the world as one to discover. Great blog.

Fabulous tale! I had tears in my eyes, and I appreciate the distinction you point out between “adventure” and “quest.” This was both!

Absolutely wonderful story.

Very cool. O.W. was my great great grandfather on my mom’s side. Both my parents, her parents, grandparents are buried with them at the Pleasant Hill Cemetery, there out of Nacogdoches. I have been trying to learn more of fheir history, but do not have anyone that i know to discuss the family history with.