- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Putting the People Back in Camp Naco

Camp Naco saw more than 500 visitors in the two days after Thanksgiving as part of the annual Bisbee Home Tour. That’s more people than were ever stationed there at one time!

The association of Archaeology Southwest with Camp Naco started a decade ago when Becky Orozco, now of Cochise College, led a small group tour that I was on. Two years later, our Archaeology Southwest Magazine featured the archaeology of the borderlands and Camp Naco was a prominent theme.

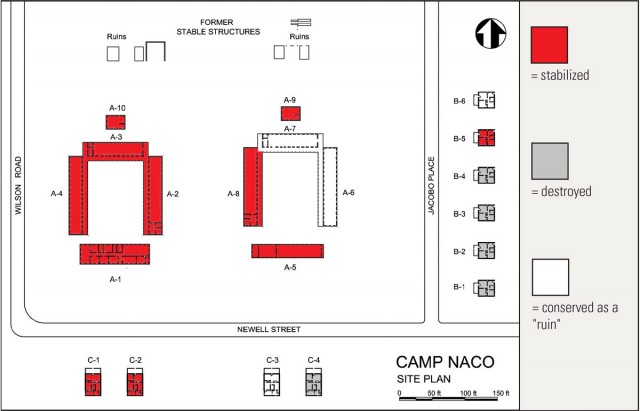

And ever since, there has been a constant cycle of grant writing, fundraising, completion of a National Register nomination, and outreach to any who will listen to promote and protect Camp Naco. We collaborate with Huachuca City, the property owner, and with the small nonprofit Naco Heritage Alliance. The result is eleven adobe buildings stabilized, an asbestos-free Camp, and the ability to finally open the gates and put on a large-scale public tour.

Nearly all of my time at Camp Naco since spring of 2008, when the perimeter fence was installed, has been solo or small-group visits. So, it was gratifying to see groups of two to twenty persons walking between the buildings and exploring one of the former barracks and the recreation center. They were interested in both the past and the future of the buildings at Camp Naco. They also wanted to know about the soldiers that were once stationed there. I wish we knew more, but there are some details we tour guides could share.

When it was active between 1919 and early 1924, Camp Naco was home to only about one hundred Buffalo Soldiers—segregated Army units of African-Americans. Unfortunately, no letters or journals from the men of Camp Naco are currently known. But the 1920 census provides intriguing glimpses of the Camp’s residents on January 30th of that year.

The census lists 94 men with a Camp Naco address. The commanding officer and the surgeon were described as white, as was one other soldier. In addition, there was one Native American from New Mexico, a Puerto Rican, five “Mulatto,” and 84 Black men. The African-American men were mostly from southern states, with over half from Georgia, Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and South Carolina.

The National Register nomination for Camp Naco states:

Soldiers ranged in age from 20 to 52 years of age, and 18 of the 94 men at Camp Naco were married at the time of service (Bureau of the Census 1920). The census data also reveal information particular to the African-American experience during the early twentieth century. Many of the soldiers were unable to provide information about where their parents were born, and because the men stationed at Camp Naco were likely the offspring of former slaves, this lack of information is not surprising. Further, all the soldiers stationed at the camp were literate. While not unusual in the U.S. military (literacy was required for enlistment), literacy rates were comparably low among minority populations even into the early twentieth century.

The opportunity to return a public audience to Camp Naco highlighted to me the need to continue the research process so that we can do a better job of putting the past residents back in this place by telling their stories. The historical record is thin for the time that Camp Naco was active, but small details from both documents and archaeology can still be gleaned with focused work. The story of the Civilian Conservation Corps‘ use of the Camp from 1935 to 1937 definitely merits more attention. And there are many local families who rented from the long-term property owners, the Newell family, and lived in one of the ten former officer’s quarters along the perimeter of Camp Naco. Their stories need to be gathered, as well.

Explore the News

Related to This

-

Project Saving Camp Naco, Arizona

-

Post Onward, Camp Naco!