- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Contrasts

Connor Walsh, University of Notre Dame

Several months ago, when I was considering my options for an archaeological field school, I hoped to choose a school which would broaden my experience; all of my previous work was in Ireland, and I knew that my base of knowledge was therefore limited to the idiosyncrasies of archaeology in that country. It was this need to expand my horizons which led me to the arid hills of Mule Creek, New Mexico, a place as different from the cool and grassy coastline of Co. Galway as I could imagine.

Here at Mule Creek, I have had to adjust my way of thinking about the problems of preservation archaeology. Now that the initial shock of being a northeasterner in the Southwest (bewilderment at the scarcity of water, accidental and painful encounters with prickly local flora, and the unfamiliar sensation of a perpetually dry nose) has worn off, I have begun to comprehend the unique challenges of protecting archaeological sites in the Southwest, and how they differ radically from those with which I was familiar.

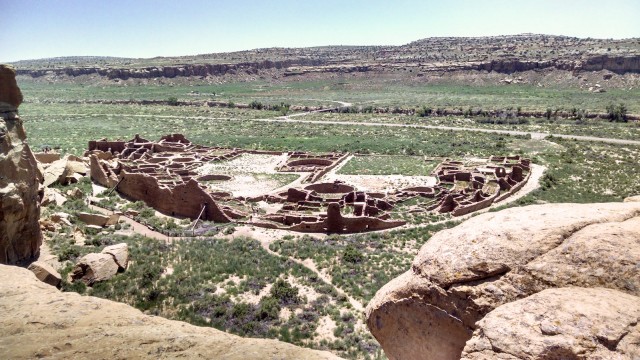

In my background in Irish archaeology, preservation had a distinct meaning: we worked to counteract or stay ahead of the environmental degradation of sites over time. My last trip was in fact a surveying project designed solely to document at-risk sites expected to erode into the sea within the year. By contrast, the environmental risk to sites in the Southwest is comparatively low. Though erosion due to monsoon rains and floods does endanger some sites, such as Elk Ridge in the Mimbres Valley, the typical climate conditions in the southwest allow structures to last far longer than in Ireland. I was amazed by what seemed the perfect condition of Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon. Most striking was the presence of original timbering, spared from rot by the absence of moisture for most of the year. Roof beams, ceiling framing and floor slats all remained fitted together as tightly as the day they were made. I was awestruck; the same timbers in Ireland would have begun to disintegrate after only a few decades if untended by the original residents.

On the other hand, I have learned that here the threats of development and looting loom large. Paul Reed, while guiding us through the major sites of Chaco, illustrated just how much of a threat development poses to archaeology here, indicating a sweeping view of the area beyond Pueblo Alto and describing the major oil and gas drilling operations being planned for the spot. These were new considerations to me, as most important archaeological sites in Ireland have either already been excavated or are thoroughly protected by law. The possibility of Chacoan roads and pueblos being wiped out for commercial purposes drove home to me the vital importance of rescue and preservation archaeology here, where a site that had survived a millennium can be destroyed by the bulldozer in an afternoon.

I realize, of course, that these observations are only the most general and easily grasped particularities of archaeology in this region, and those with much more experience than myself working in the Southwest could doubtless highlight many more points of diversion—and similarity—between the Irish archaeology I know and this desert work I am just beginning to understand. Even so, I feel as though at Mule Creek I have gained what I had hoped: not merely a familiarity with the subjects of archaeology in the Southwest (or a perpetual sunburn), but with some of its objectives and obstacles as well.

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.