- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Ancient Engineering: “Hanging” Canals

Archaeology Southwest is honored to feature “The Prehistoric Bajada ‘Hanging’ Canals of the Safford Basin: Small Corporate Group Engineering in Southeastern Arizona,” written by James A. Neely, Professor Emeritus, University of Texas, and co-researcher Don Lancaster of Thatcher, Arizona, especially for our Preservation Archaeology blog. This update follows on Dr. Neely’s post from April 2014.

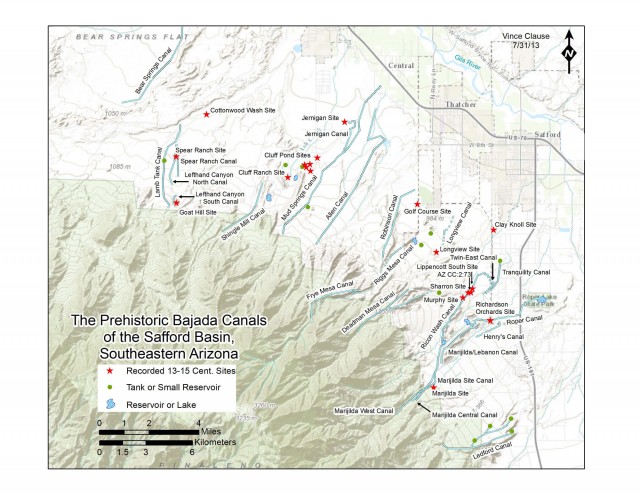

(October 5, 2015)—Ongoing archaeological survey in the arid Safford Basin has disclosed a series of exceptional small prehistoric canals (Figure 1) that have expanded our knowledge of water management engineering and agricultural intensification in the American Southwest in the distant past.

These unusual canals are found in an area where other older and contemporaneous water management schemes are also present, including conventional lowland riverine canals, extensive non-irrigated terraced and gridded fields, numerous check-dams, and grouped arrays of agricultural mulch rings and rockpiles.

We have identified fifty-nine bajada canal systems and segments to date, many of which are shown in Figure 1. The longest are about 9.5 kilometers (6 miles), and the total length of all systems exceeds 112 kilometers (about 70 miles).

These canals have been difficult to date, because our study has been based solely on surface survey. We have depended on stratigraphy, surface artifact finds, and associated prehistoric sites to provide temporal parameters. Although a few canals may date as early as A.D. 800, the vast majority appears to originate after about 1250 with some persisting until about 1450.

These canal systems differ from the prehistoric canal systems found in the Phoenix area and elsewhere in the Southwest in that they obtained their water from the Pinaleño Mountain bajada drainages fed by runoff, springs, and artesian sources, rather than rivers.

They are also unusual in that they traverse the vertically undulating to severely erratic uplands of basin and range topography, rather than being restricted to a nearly level riverine floodplain. Some carry their water load from over 1650 meters in elevation (just over 5400 feet) down to just above the floodplain of the Gila River at about 900 meters (just over 2950 feet). The difficulty in the original excavation of these systems was further intensified by the very rocky nature of much of the terrain they traverse.

In more level terrain, the canals are of the traditional type—narrow, linear excavations into the ground surface that follow the contours of the landscape. In other locations within the same canal system, they appear as “perched” or “hanging” canals traversing the sheer sides of mesas – with some coursing 60 meters above the adjacent basin floor (Figure 2).

The canals often create the illusion of water flowing uphill, in that the mesa top slope is usually somewhat steeper than the rate of fall of the canal itself. In these latter cases, the perched or hanging segments are designed to follow the most direct route and are essentially independent of their surrounding terrain. This reduces the energy input needed to excavate additional canal length to follow the irregularities of the topography. Such construction would also reduce water loss through seepage and evapotranspiration.

After reaching a mesa top through a long, gentle, and an evidently carefully calculated optimal grade, and then continuing as far as possible along the usually flat but gently sloping ground surface, the canals will typically “fall off” the far end of the mesa in steep but apparently highly controlled and nondestructive cascades descending in nearly vertical constructions, similar to French Drains.

Canal cross-sections (Figure 3) at the ground surface vary from 30 centimeters to one meter, and 20 to 40 centimeters in depth. Atypical examples may range as much as two to three meters in width.

As with many of the Gila River bottomland canals of the area, the historic inhabitants of the greater Safford area refurbished some of these prehistoric canals, and several reaches of the canals still flow to this day. However, most retain enough integrity to be recognized as having a prehistoric origin. In particular, short “low energy” segments remain extant and highly suggestive of prehistoric origins.

Portions of most of the systems remain almost pristine, and are currently filled with fine-grained sediments. These systems are located mostly on Arizona State and Coronado National Forest lands that remain largely undeveloped.

While often of difficult access, as there are few roads and fewer mesa top trails, major canal portions are usually easily traced on foot and by satellite imagery, such as Acme Mapper. Unfortunately, both historic and modern constructions and land modifications, mostly near the terminus of the canal, have negatively affected these systems.

A number of unusual constructions were incorporated into some of these canal systems; following are three examples.

- First, an aqueduct, about one and a half meters (almost 5 feet) in height and 80 meters (about 262 feet) long, was constructed to bridge a “saddle” in the topography associated with a prehistoric segment of the Lebanon Canal.

- The second example is at a point where the primary Frye Mesa Canal is situated near the top edge of the mesa, a branching “counterflow” canal was excavated down the mesa slope at an acute angle apparently to irrigate fields lying below and behind the point of branching.

- A third example is a three-meter wide and two-meter deep segment of the Allen Canal. Due to its size we have referred to it as the “Culebra” cut.

Several canal systems illustrate elaborate methods of purposeful switching of the water routes from canals to natural drainages, and then back to canals. In sum, these systems appear to represent a major understanding and a very careful exploitation of the topography and hydraulic fundamentals, as well as attention to extreme energy and use efficiency.

The discovery of these canals and our continuing survey in the Safford Basin suggests that the basin was a prehistoric population center and a major supplier of cultivated crops. Their use seems to be primarily long distance water delivery to fields, but the canals also apparently supplied water to small habitation sites and complexes.

Survey in Lefthand Canyon (near the west boundary of our survey) and Marijilda Canyon (near the east boundary of our survey) has recorded a rather heavy population scattered along the canals, but the sites are nearly all small. To date, survey along most of the other canals has recorded only a few small sites.

These findings provide evidence in the form of agricultural intensification and settlement that points to a sociopolitical organization based on the collaboration and collective action of small corporate groups rather than a more complex social stratification and socio-political structure. These findings parallel a study (see readings below for Hunt et al. [2005]) focusing on the nearby Hohokam area.

Ceramics and house remains from contemporary habitation sites indicate both trading activity as well as actual residence by several of the prehistoric cultural groups of the Southwest including the master canal builders of the Phoenix area, the Hohokam. It is likely that the canals were engineered and constructed by the local Safford Basin inhabitants, due to the presence of conventional lowland riverine canals dating as early as ca. 190 B.C.

As the associated sites, with Salado ceramics and architecture, date to the period of ca. A.D. 1250–1450, the bajada canal systems appear to have largely been engineered and constructed by the then resident northern migrants. However, due to the apparent near absence of canal systems in the Four Corners area, the Hohokam presence noted above makes us wonder if the contemporaneous Hohokam residents may have at least in part assisted in engineering the later more sophisticated canal constructions.

The engineering involved in the planning and construction of these canals seems phenomenal considering the lack of leveling instruments and metal tools. It would appear possible that pilot extensions of the canals themselves could have served as water levels in spite of the tedious and time-consuming application involved.

Engineering can be defined as a sense of the fitness of things. Aptly meeting this criterion, the Safford Basin bajada canal systems are a highly sophisticated innovation that is superbly energy optimal and a brilliant engineering solution for reliable water transport and delivery over the basin and range topography of the area. They are a phenomenal prehistoric adaptation to an arid environment to irrigate agricultural fields distant from once apparently abundant water sources.

Learn more:

Don Lancaster’s website

Doolittle, William E. and James A. Neely (editors)

2004 The Safford Valley Grids: Prehistoric Cultivation in the Southern Arizona Desert. Anthropological Papers of the University of Arizona 70. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Huckleberry, Gary

2005 Geomorphology of the Safford Basin and Canal Studies at Epley’s Ruin, AZ CC:2:64 (ASM). In Archaeological Investigations along US 70 and State Route 75 from Solomon to Apache Grove, Graham and Greenlee Counties, Southeastern Arizona, V2, Epley’s Ruin (AZ CC;2:64 [ASM]): A Long-Lived Irrigation Community in the Safford Basin from 200 B.C. to A.D. 1450, edited by Annick Lascaux and Barbara Montgomery. Tierra Archaeological Report No. 2005-94. Tierra Right of Way Services, Tucson. Draft report in review.

Hunt, Robert C., David Guillet, David R. Abbott, James Bayman, Paul Fish, Suzanne Fish, Keith Kintigh, and James A. Neely

2005 Plausible Ethnographic Analogies for the Social Organization of Hohokam Canal Irrigation. American Antiquity 70(3):433–456.

Neely, James A.

2005 Prehistoric Agricultural and Settlement Systems in Lefthand Canyon, Safford Valley, Southeastern Arizona. In Inscriptions: Papers in Honor of Richard and Nathalie Woodbury, edited by R. N. Wiseman, T. O’Laughlin, and C. T. Snow, pp. 145–169. Papers of the Archaeological Society of New Mexico 31, Albuquerque.

Neely, James A.

In Preparation Prehistoric Settlement and Agricultural Systems in the Marijilda, Rincon, and Graveyard Wash Areas, Safford Basin, Southeastern Arizona. To be submitted to the Arizona State Museum and the Coronado National Forest, Tucson.

Neely, James A. and Everett J. Murphy

2008 Prehistoric Gila River Canals of the Safford Basin, Southeastern Arizona: An Initial Consideration. In Crossroads of the Southwest: Culture, Identity, and Migration in Arizona’s Safford Basin (Proceedings of the AAC Fall 2005 Meeting), edited by David E. Purcell, pp. 61–101. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle, UK.

Purcell, David E. and Jeffery J. Clark

2008 Multi-Cultural Communities in the Safford Basin. In Crossroads of the Southwest: Culture, Identity, and Migration in Arizona’s Safford Basin (Proceedings of the AAC Fall 2005 Meeting), edited by David E. Purcell, pp. 39–59. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle, UK.

3 thoughts on “Ancient Engineering: “Hanging” Canals”

Comments are closed.

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.

Tours of the canals can be arranged, and co-researchers are more than welcome.

don@tinaja.com

928 428 4073

More at http://www.tinaja.com/tinsamp1.shtml

Ongoing developments at http://www.tinaja.com/whtnu15.shtml

Bravo Dr. James A. Neely and Mr. Don Lancaster I am encouraged that someone has further investigated in much greater depth my single identification in 1985 (Hubbard 1987: pp. 308-320) using aerial imagery to identify a canal currently reported in your paper as the Bear Creek Canal. It was obvious to me that the entire northeastern slope of the Pinaleno Mountains was rife with prehistoric sites and water control features, as well as prehistoric fields now completely destroyed by modern agricultural development. Now I am hoping that there will be more investigations further to the north and northeast, particularly in the Mimbres and Black Mountain ranges where I located an incredible array of prehistoric terraces identified fortuitously identified on BLM B/W imagery taken after a snow in march, 1937. Those features included several hundred square miles of terracing. Onward through the fog! Rick

A professional tour is planned for early next week with Dr. Neely and others, possibly Tuesday and Wednesday or Wednesday and Thursday, along with a Gila Watershed Alliance lecture presentation in Safford on Wednesday night.

Please contact don@tinaja.com or 928 428 4073 if you have any interest in attending these opportunities.