- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Fateful Bananas

Between now and October 17, 2015, Archaeology Southwest is participating in the Archaeological Institute of America’s celebration of International Archaeology Day (10/17/15) by sharing blog posts about why—or how—we became archaeologists. Today we feature Jeffery Clark, Preservation Archaeologist at Archaeology Southwest and Adjunct Associate Professor, University of Arizona. Previous posts in the series are here.

(October 13, 2015)—Like Leslie, my path to archaeology has been long and winding, with a few detours and dead-ends. I think I was fated to become a Hohokam archaeologist because my first experience was sneaking out after middle school and collecting sherds from a site that was being destroyed by construction near the former Williams Air Force Base, east of Mesa. I still have those sherds “curated” in a box.

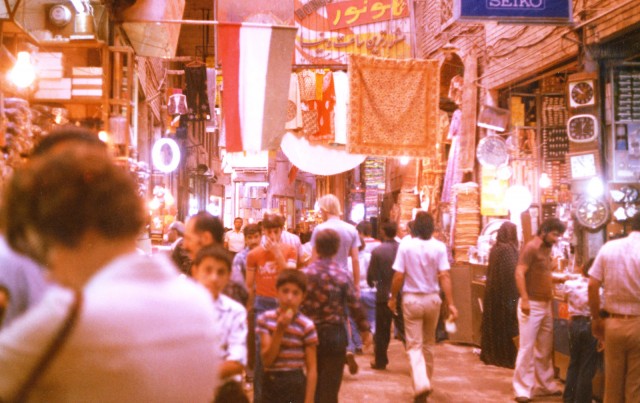

My first real interest in archaeology, or at least ancient history, developed when my family moved to Tehran, Iran, in the 1970s. As a naive American high school student, I was awed and fascinated by the millennia of Persian history that surrounded us. This sense of deep history was reinforced by some wonderful teachers at Tehran American School. The U.S. Bicentennial, a big deal at the time, suddenly paled in comparison.

Unfortunately, political events forced us to leave Iran rather hastily midway through my senior year, never to return. I spent my last semester of high school in Nebraska experiencing a healthy dose of reverse culture shock.

After a year at a small college doing some soul-searching, among other activities, I transferred to Cornell and majored in chemistry. I liked organic chemistry, especially predicting and then figuring out what one had made after mixing a bunch of dangerous chemicals together in a somewhat controlled environment. I love puzzles—the archaeological record is a puzzle to me—and this was high-tech puzzle solving. More importantly, my dad, who was paying the bills through undergrad, liked organic chemistry for its career potential.

For fun, I took archaeology classes as electives and even spent summers on local excavations, enjoying the only pleasant outdoor season in upstate New York. It was made very clear to me, though, that archaeology was a hobby for rich people and not a profession. Even the director of the archaeology department encouraged me to stick with chemistry!

At the same time, he was in dire need of undergraduate students to maintain the program, so he devised a plan whereby I could double-major in archaeology if I joined him on an expedition to northern Chile during my last semester. I had finished all my chemistry coursework, so how could I refuse an archaeological adventure, another degree, and 15 credit hours of probable “A” for a GPA boost?

To do justice to the four months in northern Chile would require a separate post. We excavated an Inca road station and surveyed remote dried lakes for Paleoindian remains. Our merry little band included future notable Southwest archaeologists James Snead and Jonathan Damp. Preservation of textiles and other perishables was incredible since we were in the Atacama Desert, one of the driest and most desolate places in the world. We spent our breaks on the beautiful beaches of Arica, a quaint free-port nestled between Chile and Peru. We also toured all the major sites in northern Chile and Peru. We lived like royalty, because the Chilean currency was kept artificially high under Pinochet’s iron fist. We traded our dollars on the thriving “mercado negro” many times above the official rate.

Shortly upon returning, I graduated and reentered the “real world.” I got a job in the research division of a pesticide company outside of Philadelphia. I enjoyed Philly immensely, but after a year and half, I concluded that the world of pesticide chemistry was not for me.

A like-minded friend and I decided to pool our meager resources and go on some kind of adventure. Many of our fellow chemists, like hobbits, thought we were crazy. I also wanted to regroup, collect my thoughts, and get back to Southwest Asia. Volunteering on a kibbutz in Israel seemed like a good choice: it was cheap, in the right place, and sounded adventurous. I actually vowed not to return to the U.S. until I had a new plan.

Once in Israel, we were assigned to a kibbutz in the northern Jordan River valley abutting the Jordanian border. This fertile area lies about 500 feet below sea level, making it ideal for banana and cotton cultivation. My friend was assigned to the cotton fields, and I got bananas. This may seem a bit off-topic, but bear with me, because otherwise I might still be at the kibbutz.

Never, ever take a job in a banana field. Banana “trees” are squat leafy behemoths that in fields form a dense and endless canopy at head level. The canopy is infested with rats, snakes, and numerous banana-loving insects (all insects love bananas). In this particular case, claustrophobia was not allowed, because if one went off running and screaming toward daylight, one might end up in the minefield separating Jordan and Israel. Up to 150 pounds of bananas grow in a single multi-tiered “megabunch” attached to the tree by a thick stalk. One of my primary jobs was to catch these megabunches “gently” on my shoulder after the stalk was sliced to free-fall for about 3 to 4 feet. The stakes are high—if you drop the megabunch, every banana (literally, hundreds) is ruined.

On the plus side, the job was mindless and we only worked about 5 hours a day for 5 days a week. Every fourth week was an unpaid vacation, so I had plenty of time for thinking and traveling. I hitchhiked and bussed around Israel, visiting sites dating from the Neolithic through the Roman Era. Jerusalem, Jericho, Nazareth, Bethlehem, Har Megiddo/Armageddon, and Masada were all within an hour or two’s drive. After about 3 months, I ended up at the doors of the neo-colonial Albright Institute of Archaeology in Jerusalem. I met the director in the lobby as he was preparing logistics for an upcoming field season at the site of Tel Miqne-Ekron, an important Philistine city mentioned in the Bible. Given my previous experience, he offered me room and board to supervise a unit.

Hmmm…back to the bananas, or on to Ekron? I left the kibbutz and moved in with the excavation team. Shortly afterward, I met Jonathan Mabry and a couple of other new University of Arizona graduate students who were also supervisors. This UA contingent was doing some very interesting research, applying anthropology to Biblical Archaeology, and I was hooked.

After the excavations were over, I had a plan and returned to Philly. While working some odd jobs, I applied to the UA anthropology department and was accepted mid-term, thanks to Norman Yoffee, who became my advisor. I packed my old Volvo and a small U-haul trailer with my possessions and drove cross-country to Tucson in January 1986. The rest is (pre)history…

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.