- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Bears Ears and the Issue of Ownership

This post was originally published on September 23, 2016, on the Binghamton University MAPA blog, http://mapabing.org/2016/09/23/bears-ears-and-the-issue-with-ownership/. Re-posted courtesy of the author and with the original blog’s permissions.

(September 23, 2016)—Howdy!

This week I return to our “regularly scheduled programming” and discuss the issue of ownership in relation to archaeology and public lands. The question “who owns the past?” arises wherever there is contestation over cultural heritage between groups. Conversations about ownership have hinged on the ethical considerations surrounding portable artifacts, antiquities, and human remains. Examples include the return of the Euphronios Krater to Italy, the recent sale of Hopi Katsina friends (or masks) in a Paris auction house, England’s stubborn refusal to return the Parthenon Marbles to Greece, and the long controversy over the repatriation of the Ancient One (Kennewick Man).

The ownership of portable cultural patrimony is a huge, fraught issue that isn’t going away. Dozens of books discuss cultural patrimony and ownership. However, the debate is a bit different when we talk about cultural sites and landscapes that cannot be moved (unless you’re Carmen Sandiego!). The issue of ownership is no less applicable in the case of cultural landscapes, though it is the ability to make decisions about management of particular places that is at stake.

This is a lengthy post, so let me lay out a map on the hood of the truck and give you some directions. I am first (#1) going to discuss the ideology of local control, and how it has recently played out on public lands. Following that, I give a brief “archaeological” perspective on the settlement patterns of the U.S. West (#2), and how they intersected with the Antiquities Act of 1906. Then I’ll downshift a gear and really get into it – the debate over the proposed Bears Ears National Monument is where the issue of who owns public lands and the archaeology on them is occurring RIGHT NOW (#3). Finally, we arrive at the end of our trip (#4) where I consider the role of local communities in the public archaeology of the U.S. West. Luckily, this is a webpage, not a 4 x 4 road, so feel free to skip between sections as you wish.

(#1) The Ideology of Local Control

There have been political movements calling for state, local, or private control of federal lands at least since the 1870s and 1880s. Anti-government sentiment in the Western U.S. is nothing new. The current “sovereign citizen” movement has recently culminated in several high-profile confrontations on public land, such as the “Battle of Bunkerville” a.k.a. the Bundy Standoff in Nevada, the Malheur Occupation in Oregon, the Recapture Canyon protest ride in Blanding, Utah, and many other smaller acts of resistance to federal control. In at least two of these instances (Malheur and Recapture Canyon), archaeological sites were damaged by protesters.

The crux of the issue is whether local communities adjacent to public lands ought to be the only people responsible for deciding how those lands are managed and what kinds of activities are allowed on them. The ideology of “local control” developed as a result of the specific combination of culture, environment, and history found in the American West. It is impossible to understand the contemporary U.S. West without considering how 19th century American social relations (including gender, class, and race) collided with the ecological conditions west of the 100th meridian (Wallace Stegner explored this in fantastic prose in Angle of Repose, and other novels).

(#2) Western Settlement Patterns, Homesteading, and the Antiquities Act

One of the key components of the settlement pattern in the Western United States is that owning a small portion of private land allowed for control over a vast extent of public land. This land had been violently wrested from Native Americans and subsequently alienated from the public commons at bargain rates. A Western stock-raising operation might actually own only 320 or 640 acres of land (about 1 square mile), but if this property was strategically positioned next to the public commons, it might allow a rancher to control tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of acres of summer forest and winter grassland range that was actually public commons. Strategic positioning near railroads and water sources were also key considerations. If you’ve ever played Carcassonne or Settlers of Catan, you’ve experienced a (vastly simplified) version of the late 19th and early 20th century land grab across the West.

Western settlement patterns are therefore fundamentally structured around the existence of public lands. But that does not mean that these spaces necessarily “belong” to adjacent communities. Since the late 19th century, the federal government has consistently shown a commitment to conserving and regulating resources on public lands, evident in the passage of legislation such as the Land Revision Act of 1891 (creating national forests to regulate timber cutting and grazing on public lands), the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 (to regulate stock grazing on public lands), and the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (formalizing a policy of “multiple-use” for public lands).

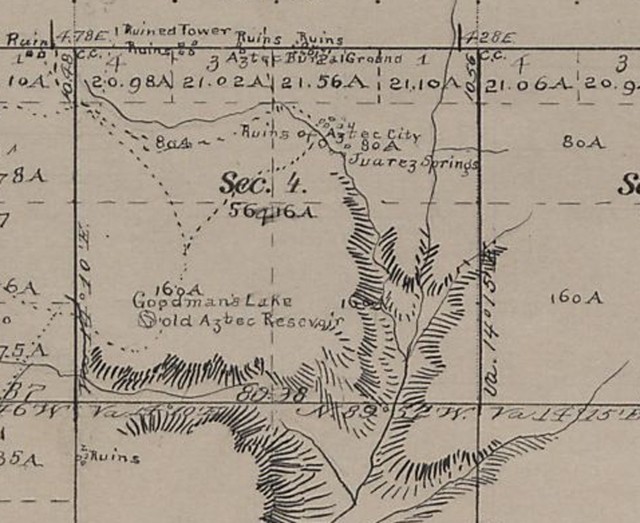

The federal government also sought to preserve and protect archaeological remains on public lands from an early date. To illustrate this, I have to look no further than my own (former) backyard in Montezuma County, Colorado. Homesteading during the late 19th and early 20th century was not a complete free-for-all. Regional land offices conducted surveys, chose which areas to open to homesteading, and often prohibited homesteading in certain areas or reserved valuable resources for the federal government. So in 1889 when land surveyors identified a particularly notable series of ruins on Goodman Point, in Montezuma County, Colorado, the U.S. Surveyor General in Denver chose to reserve the section from homesteading, thereby creating the first federally-protected archaeological site in the country.

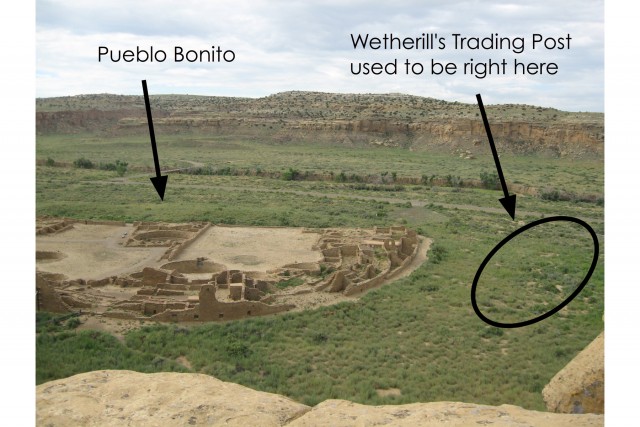

The 1906 Antiquities Act, mostly written by archaeologist Edgar Hewett and signed by Teddy Roosevelt, also affirmed the government’s commitment to protect cultural resources. The Antiquities Act is a key piece of legislation that not only prohibits the collection of artifacts and disturbance of sites on federal land, it also gives the president the power to create national monuments. Its origins lie in power struggles between the government, moneyed private interests, and local communities, played out on public lands. Generally speaking, the Antiquities Act was a response to the immense volume of antiquities vacuumed off of public land in the U.S. Southwest between 1880-1900. More specifically, however, it was a response to Richard Wetherill’s homestead and trading post at Pueblo Bonito, in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. (There’s also a Mesa Verde connection, but if I follow that lead, too, we’ll never get to the end of this post!).

Wetherill homesteaded Chaco Canyon while working as the chief excavator for the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) Hyde Exploring Expedition. The Antiquities Act provided legislative clout to eject Wetherill and the AMNH from Chaco—and allowed Edgar Hewett to take their place as the primary Chacoan archaeologist of the early 20th century. So, East Coast money (AMNH) was channeled through a local citizen (Wetherill) to exploit archaeological resources on public land (Chaco Canyon); in response, a private citizen (Hewett) enlisted the help of the federal government (Congressman John Lacey, sponsor of the 1906 Antiquities Act) to eject a potential rival from an archaeological treasure (Pueblo Bonito). Within one year of its passage Chaco Canyon was a national monument, and within four more years Richard Wetherill was dead (murdered) and Marietta, his widow, had moved out of the canyon.

Now, I think that history has given Richard Wetherill a bit of a bad rap—he was in fact a skilled and conscientious archaeologist. But I find little sympathy for modern day opposition to the Antiquities Act. At the moment, this opposition is most visible in the debate over the proposed Bears Ears National Monument in southeast Utah.

(#3) The Proposed Bears Ears National Monument

While the #NODAPL movement at Standing Rock is bringing attention to indigenous perspectives on landscape, resource use, and the frequent failures of tribal consultation (see my previous post on DAPL here), a related issue is simmering in southeast Utah. The Cedar Mesa region is one of the most spectacular landscapes in the world, combining stunning red rock canyons with some of the best preserved archaeological remains in the world. It is also the scene of a major showdown between native tribes, local communities, environmentalists, archaeologists, and several Congressmen.

The backstory on the possibility of a Bears Ears National Monument is somewhat complicated. For longer discussions of the history of the proposal, I’d suggest reading Jonathan Thompson’s excellent coverage in High Country News. Although environmental protection is one important aspect of the possibility of creating a national monument, the principal reason that people want to protect the Bears Ears region is because of its importance as a cultural landscape and because of the astounding wealth of archaeological sites contained within its red rock canyons. Figuring out how to manage cultural landscapes like the Bears Ears/Cedar Mesa region will be a fundamental issue for public archaeology in the next few years.

In a nutshell, there are two competing visions for protecting the Bears Ears area, though they sprang from the same coalition five years ago. On the one hand is the inter-tribal coalition which is pushing for President Obama to use the Antiquities Act to designate a 1.9 million acre national monument. They are joined by many conservation groups, archaeologists, and outdoor recreation enthusiasts. On the other hand are the supporters of the Public Lands Initiative (PLI), a counter-proposal to a national monument led by the offices of Utah State representatives Bob Bishop and Jason Chaffetz. The PLI plan involves protecting a significantly smaller area using the existing framework of National Conservation Areas, Wilderness Study Areas, and other special use areas. The PLI garners much of its support from local San Juan, Emory, and Grand county residents, although there is some support from one of the Utah Navajo chapter houses, and from some members of the Ute tribe.

I attended the most recent public meeting concerning the monument that was held in Bluff, Utah, back in July (for a video of the entire proceedings and all public comments, go here). I was struck by how divided the Native American contingent was, with many local Navajo and Ute strongly opposing the designation of a national monument. But if we return to the concept of ideology I presented at the beginning of this piece, I think it begins to make sense. Ideology is an outgrowth of people’s interactions with each other as well as with the material conditions of their daily lives–in this regard, Native stock growers have much in common with the Anglo stock growers who also oppose the national monument. And historically, the federal government has not worked in the best interests of the indigenous peoples of North America (a couple Utes and Navajos at the meeting reminded the crowd of the historical injustices towards Native peoples by the U.S. government). There is some irony to this somewhat unholy alliance between Native and Anglo stock growers, as the ancestors of many of the Anglo ranchers were the same people who, with the assistance of the federal government, had pushed Ute and Navajo peoples off the public lands of southeast Utah during the 1900–1950s.

I was also struck by the comments of a local Anglo resident who had been an employee of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the Forest Service. He pointed out that the BLM and Forest Service do not have enough enforcement rangers to adequately patrol the region. However, given the state of budget appropriations in Congress at the moment, it’s not likely that designating the Bears Ears area as a national monument is going dramatically increase the number of enforcement rangers, archaeologists, or maintenance staff in the region. So southeast Utah could be stuck with a new crown jewel National Monument that drastically increases visitation to the area, but without any of the infrastructure to cope with the influx. Furthermore, while I am generally against rampant resource extraction from our surprisingly fragile Western public lands, I can’t help but agree that recreational tourism tends to create more low-wage, service-sector jobs than higher paying, development-sector jobs. A monument could have dramatic unintended consequences on local jobs and infrastructure.

However, despite holding reservations about the actual benefits of a national monument designation, there is no way I can support the proposals outlined by the PLI coalition. The same coalition of congressman, think-tanks, and citizens that are at this very moment pushing the PLI proposal through the house of representatives, are simultaneously attacking the president’s power to use the Antiquities Act to protect cultural resources on public lands. There are numerous bills making their way through Congress that would restrict the size of national monuments to under 5,000 acres, prohibit the designation of national monuments in particular states or counties, or make any monument designations subject to state approval. If any of these changes are made, the effects could be devastating to public archaeology in the Western U.S. I have many friends who have considered abstaining from voting this election cycle, but elections aren’t just about the president—keeping representatives and senators in Congress who support conservation and preservation of cultural resources is absolutely critical for public archaeology.

(#4) The “Locals Only” Question: Who Do Western Public Lands Really Belong To?

My task is now to try and tie all these various threads together. You may be asking, “Why the hell did Kellam hit me with ideology, bore me with some historical details on the Antiquities Act, then ramble on about various factions duking it out in canyon country over the Bears Ears National Monument?” Let me tell you.

The “locals only” ideology is an outgrowth of the settlement patterns of the U.S. West. Based on the history of settlement, you could say the Western ideology is a libertarian one of personal freedom, limited government intervention, and private appropriation of public commons. But by the same token, you could say that the Western ideology is one of conservation and preservation of public commons for public good through initiatives like the Antiquities Act.

At the public meeting in Bluff, San Juan County Commissioner Phil Lyman stated (at 1:43:28 in the Bears Ears public meeting video) that Utah doesn’t need any more protections for artifacts—”as far as the rules to protect artifacts there is a law in place it’s called ‘don’t steal’ and people understand that.” But Lyman’s own involvement in the Recapture Canyon protest ride speak differently, as do my experiences documenting dozens and dozens of pothunted Ancestral Puebloan sites within the proposed national monument. It is not at all evident that the ethic of stewardship has been the defining characteristic of the “local” relationship with archaeology on public lands in southeast Utah. And it’s not just about artifacts, it’s about the non-movable archaeological sites and sacred sites, as well.

Furthermore, the appeals to nativism that I’ve observed among some members of the Anglo community in southeast Utah ring hollow. During the public comment period at the meeting in Bluff, many people began their testimony by reciting their genealogical heritage in the region—for Anglos, this history reaches back to Mormon colonization during 1879–1880 Hole-in-the-Rock expedition. I found the use of this rhetorical style as an explication of use-rights more than a little ironic in a room full of Ute, Navajo, Hopi, and Zuni peoples.

There is no inherent reason that people living next to public land should have more say over its management than conservationists from 1,000 miles away. It’s public land, and “the public” is a diverse group. I am unconvinced that “local (Anglo) communities” in the West should have disproportionate power and authority to dictate land management strategies, particularly considering the importance that cultural resources on those lands hold to Native peoples. This position is contrary to many perspectives in community-based archaeology. But I think that in the case of Western public lands and the cultural resources found on them, the history of power relations forces us to think and act differently.

It’s a fact: the public lands of the West were created through the displacement, destruction, and disenfranchisement of Native American communities. This fact should guide decision making at all levels in public archaeology. We should pay close attention to the fact that it was native communities in the Four Corners states that are using the tools of federal government to protect their cultural heritage off-reservation, and on public lands. And so I’d like to turn to a statement from Zuni Elder Octavius Seowtewa (found at 1:39:15 in the Bears Ears video) to finish up here:

“I did some…interpretation of Zuni words yesterday, and I would like to say that here for people to hear and understand that when we talk about these places in Zuni we call it ‘our ancestors.’ And I mentioned yesterday it’s not talking about Zuni ancestors, it’s not talking about Hopi ancestors, Navajo ancestors, it just mentions ‘our ancestors.’ And that’s one of the key reasons that I’m really in support of the Bears Ears [National Monument]. Because with that language, with what we understand about this place is that we need protection….I heard some archaeologists talk about their Western teachings and we thank them for that because without their work we wouldn’t have that information out there. But, what’s lacking is the traditional knowledge from the native people. And so looking at this place I’m looking at some ideas of making a traditional knowledge institute that would be working with the archaeologists and all the tribes that are here would benefit from working with archaeologists because they’ll gain more from us as well as gaining from them. And I think that would be the way to go in preserving what is still there. And that’s one of the reasons why that the protection is looked at by all of the tribes and all animosity, all ill feelings aside we all came to the table and talked about how we can manage, collaboratively manage this area.”

I’m not sure how expansively Mr. Seowtewa is using the word “our.” I am certain he means all the native tribes in the inter-tribal coalition. I’m not sure if he extends it to non-native peoples. But perhaps if non-natives tried a little harder to understand the indigenous perspectives on these public landscapes, they (we—I’m a descendant of Western colonists; but I’ll spare you my genealogy) might find new ways of respecting and managing them.

Rightly or wrongly (well, for the most part wrongly) we (Anglo-americans, in my case) have inherited public lands. I’m not sure that means we own them. And this puts an amazing onus on public archaeology. As a discipline, craft, and profession, public archaeology is situated in a critical intersection between: 1) the power of the state, as embodied in laws and regulation, 2) various interest groups with varying access to power, such as indigenous groups, landowners, corporations, and federal agencies, 3) the “public interest” as an abstract concept, 4) and the material world, which includes historical sites, archaeological sites, and culturally important landscapes and places. In order to help manage without being patronizing or paternalistic, public archaeology is going to have to listen carefully.

Kellam Throgmorton is a PhD student in Anthropology at SUNY Binghamton, New York. His research interests include the archaeology of the U.S. Southwest, cultural resource management, and public lands issues. He has lived and worked in the Four Corners region for more than a decade.