- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Mother Bear’s Ears

(June 17, 2017)—In the summer of 2004, two friends and I traveled from our seasonal home at the Grand Canyon down to Flagstaff to see Ani DiFranco in concert. Ani and I are both from upstate New York, and although I have been a fan of hers since my late teens, I had somehow never caught her in concert before. She played at Northern Arizona University, where I would wind up a year later studying archaeology, and partway through the set she recited a poem she’d written about the Grand Canyon. One of the lines was, simply, “Why don’t more men call themselves feminists?”

This gave me pause. Why indeed?

It took a bit of studying social science for me to figure out a simple answer to that question, which is basically that a lot of otherwise good-minded people are more afraid of being lumped into stereotypes than they are steadfast in their convictions. But the bigger element is this: there are no requisite criteria for being a feminist, or a conservationist, or any other type of socially conscious person. The only requirement is to make an earnest and sincere commitment, in this case to gender equality. After hearing Ani’s plaint, I felt emboldened to inform my friends and colleagues that I—a straight male with a square jaw and a hairy chest—am very definitely a feminist. They were surprised it took me that long to realize it.

This past U.S. election was felt as a blow by feminists and many other progressivist groups, and it was an especially acute blow for Native American rights activists and their supporters, because it very likely spelled the end of the two most successful Native-led and Native-oriented efforts in recent history. One, the Standing Rock protest, went about how you’d expect. I defer to others to tell that story.

The other one is Bears Ears National Monument—and that story is still unfolding.

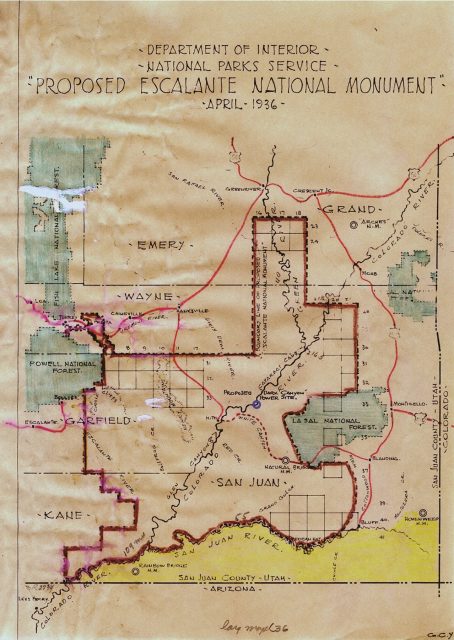

In many ways, the Bears Ears designation is a result of years of pent-up exasperation. Efforts to enwrap the place in monument-level protection date back to the 1930s, the biggest of which was on the fast track to designation until it got waylaid by World War II. Various proposals for National Conservation Areas were engineered during the intervening time, many of them by Native American groups and their supporters, but all of these proposals fell before the relentless onslaught of Utah’s idiosyncratic brand of politics.

The final straw was several years’ worth of distracting “consultation” leading up to the Public Lands Initiative (PLI), a state-sponsored alternative to the monument, which included reams of testimony by tribal representatives and conservationists, all of which was ultimately ignored. The final version of the PLI passed from its creators’ hands straight into Congress’s trashcans. Designation of Bears Ears National Monument came a few months afterward.

The significance of Bears Ears to all people, indigenous or otherwise, is far too complex a topic to completely unpack here. But there’s a reason I introduced this piece with my light-bulb moment about feminism. At the Celebrate Bears Ears event in Monument Valley this past January, Arizona House Representative Eric Descheenie explained how an overlooked aspect of the monument victory is that it is a big win for women.

Traditional narratives about Bears Ears always cast it in a feminine light, about which more in a moment, and among the Navajo at least it is a place associated specifically with feminine healing energy. As Descheenie explained, women who experience the traumas of, for example, spousal abuse, rape, or miscarriage, seek Bears Ears for healing.

This relates in turn to the role of Bears Ears in their sacred geography. Associated with Changing Bear Maiden, the twin monadnocks of Wingate Sandstone—the “ears”—represent the place where she lies following a heated exchange that erupted after she fell in love with wily old Coyote—hence the associations with things like domestic abuse.

The Hopi and Ute have their own stories, which have not been vouchsafed to me personally so I do not feel privileged to discuss them, but they share a number of elements. Hers is the place where healing plants and medicines are traditionally procured, especially—though not exclusively—by and for women. She is the guardian to the north, healer and watcher over the land and its peoples. She is Mother Bear.

In more quantitative terms:

The Utes, great lovers of horses since they were first introduced to the area (not by the Spaniards, or at least not directly, but from contact and trade with the Plains tribes to the north and east), are known to have held horse races near and between the Bears Ears. Their historic horse-racing tracks are still known and monitored by local archaeologists and historians.

And although Ancestral Pueblo groups left the area by about A.D. 1275, evidence suggests that they intended to return. Local archaeologists have documented numerous Hopi Yellow Ware ceramics throughout the Bears Ears area, as well as quite a number of historically recent Pueblo shrines, all of which suggest the ancestors of the Hopi and Zuni never planned on staying gone for long.

And the earliest tree-ring dated Navajo hogan in the entire region resides in White Canyon, in the western portion of what currently comprises the monument.

They knew the land, and the land knew them.

By comparison:

The historical epic known as the Hole-in-the-Rock Expedition set forth from Escalante in 1879 to erect a settlement at today’s Bluff. The expedition’s name derives from the fact that these indomitable pioneers, possessed of incredible determination and fortitude, had to chip and chop and blast their way through solid rock in order to traverse Glen Canyon—only to be stymied by Grand Gulch. They ended up having to circumvent nearly all of Cedar Mesa, rounding the lower uplands at Salvation Knoll before heading down Comb Wash toward the river and over to Bluff… where they discovered that the San Juan is “too thick to drink and too thin to plow,” as the saying goes, before giving up and heading north to establish Grayson (Blanding) and to oust the Spanish sheepherders around what is now Monticello.

So, the land knows them, too—but their relationship is a comparatively recent phenomenon that didn’t have much sustainability before the invention of trucks and water pumps.

The Bear knows their scent, in other words, but they aren’t her oldest or closest kin.

Turning back to the national political scene: although I wasn’t able to partake in the Standing Rock protest (outside of sending them a bunch of money), I definitely took part in the Women’s March that closely followed the presidential inauguration. In my current hideout in southwestern Colorado there’s a standing population of about 1,200, and the march included at least 500 attendees, with another 100-or-so shouting support from within their vehicles because it was punishingly cold outside. I was moved to (frozen) tears by this turnout.

I found myself marching behind a pair of older middle-aged gentlemen, seemingly a couple, who were laughing and reminiscing about Berkeley in the late 1960s. At one point I butted into their conversation, asking, “You two were at Berkeley? Like, the Berkeley?” They nodded. So then, in my own artless way, I inquired, “Do you think this will get bigger than that?”

This earned me looks of bemused condescension and suppressed laughter. “Are you kidding?” one of them asked. “This is way bigger than Berkeley. This is worldwide!”

How right they were.

Bears Ears is considered a sacred nexus of healing feminine energy for a considerable number of people. Conflating conservation of the place with the recent surge in the women’s rights movement is duck soup. They are both multifaceted issues, but at their hearts they are cultural in nature, contingent upon—and directed toward—what our culture considers valuable. The day when we protect a place because of its sacredness rather than turning it over to developers to rip apart for a quick profit is the day we can say to the rest of the world (with a straight face) that we care about something other than money, around here. That we care about people, their lives and their beliefs and stories, no matter their ethnicity or gender. And that we’ll battle ferociously to protect what we consider valuable, like the fabled mother bear defending her cubs, especially against disproportionately powerful men who just do not seem to get it.

For a personal account of healing at Bears Ears, we recommend Morgan Sjogren’s essay “Bears Ears: Run to the Sunrise.”