- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Exploring and Experiencing Places of the Past and ...

(June 27, 2017)—Our recent adventure to northern New Mexico included a visit to the Pueblo of Zuni on June 17. The community was preparing for the first day of a four-day ceremony tied to the summer solstice to bring in the new season.

We toured the Village of the Great Kivas site (late Pueblo III period, A.D. 1150–1300) on the morning of the first day of the ceremony. Before we began, our tour guide Fernando—an archaeologist and Zuni tribal member—told the Zuni creation story. He gave us a brief background on the significance of the pueblo’s location and its relation to surrounding geologic features, including the Little Colorado River and Rainbow Falls at the Grand Canyon. Mudheads, the six Shalako spirits, kachinas, and the daughter of the first Zuni cacique (an adopted Spanish word for chief) are religious figures with central roles in the creation story, and our guide explained their continued importance today.

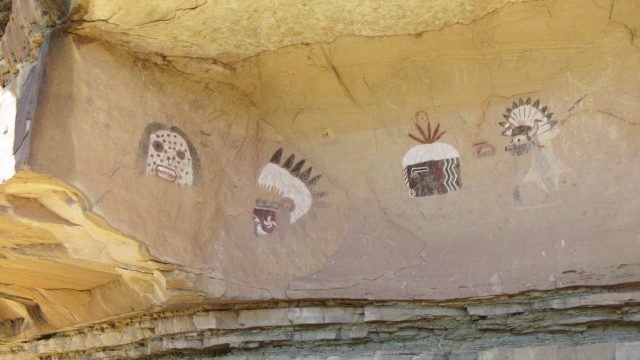

Our tour started with a short hike through brush that led us to the architectural remains of kivas. A trail made by the Zuni Youth Corps Association twisted into the cliffs behind the kivas, leading to rock faces cast with petroglyphs and pictographs. Centipedes, spiral paths, and Mudhead figures were among the various petroglyphs. Most spectacular was a wall of pictographs painted in 1935 by a Zuni sheepherder. Deep black and bright red and white pigments depicted the daughter of the Zuni cacique and kachinas, reminding us of their importance and showing one instance of a side-by-side view of pre-contact and post-contact (with Europeans) rock art. The petroglyphs and pictographs we saw on our site tour were clearly shaping Zuni people today.

Later that day, Adrianne Tsekiwa, a Zuni tribal member and PhD student at UC Santa Barbara who specializes in Zuni language, invited us to spend the afternoon with her family as they prepared for the first night of Zuni summer solstice. When we arrived, they were checking the temperature of their four hornos (a Spanish name for adobe outdoor ovens) to begin baking the rising loaves of bread that filled the tables inside. It was a hot afternoon but no one seemed to mind. There were cold drinks and a clear happiness to be spending time with family, some of whom hadn’t been seen since the previous year. When the loaves cooled, most of them would be brought to a kiva where night dances would take place, and then the ovens would be used to slow-cook sheep stew overnight.

Even though we had a four-hour drive back to Cliff, we decided to stay for the procession of kachinas at sunset. When they came into sight, the kachina images from the rock art on our tour came to life, and we were able to see a small part of a tradition that has lasted thousands of years. Despite years of colonization that limited the freedom to express this, the practices that connect people of the Pueblo of Zuni to their ancestors have endured. We saw this in the celebration of the summer solstice at large, but also through the food cooked and the Shalako houses the community builds each year.

We were invited to stay and watch the dances in the plaza, but we had to head back to camp. Although our stay was a bit of a detour, it led us to meeting some of the descendants of those who made and used what we uncover in the archaeological record in this region.

At our excavation site, we collect artifacts and then they go to the lab for analysis. It’s hard—at least for me—to connect objects to their uses and meanings. During our day at Zuni, we had the opportunity to explore the connections between the archaeological record and the practices that protect its meaning for future generations. We certainly lived Archaeology Southwest’s Preservation Archaeology mission that day.

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.