Banner image courtesy of Eastern Arizona College

Who or what is Salado?

In the late 1200s, prolonged drought and social upheaval across the Four Corners region led its residents to leave their homelands.

Among these northern peoples were groups archaeologists call the Kayenta, who migrated to already-populated valleys in the central and southern Southwest. In some places, they joined existing communities; in others, they created new settlements. Though relatively few in number, Kayenta immigrants were economically and socially influential.

In many places where the Kayenta resettled, their arrival initiated a series of changes in how people lived and what they believed. At first, tensions ensued. As a generation or two passed, though, the descendants of immigrants and local groups found ways to live together, or at least coexist as neighbors.

From these diverse communities emerged a new ideology—a new way of looking at things—that embraced aspects of local and immigrant traditions. We call this ideology—and the new traditions, practices, and objects associated with it—“Salado.”

When is Salado?

Salado emerged in the early 1300s. Its florescence continued until about 1450.

Where is Salado?

Based on the widespread distribution of Salado pottery, it seems that many Southwestern peoples participated in Salado in some way. We see the strongest evidence for Salado in southern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico.

What does Salado look like?

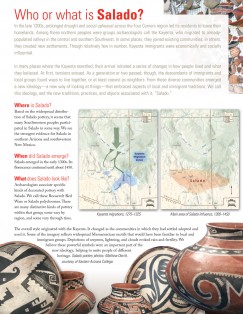

Archaeologists associate specific kinds of decorated pottery with Salado. We call these Roosevelt Red Ware or Salado polychromes. There are many distinctive kinds of pottery within that group; some vary by region, and some vary through time.

The overall style originated with the Kayenta. It changed as the communities in which they had settled adopted and used it. Some of the imagery reflects widespread Mesoamerican motifs that would have been familiar to local and immigrant groups.

Depictions of serpents, lightning, and clouds evoked rain and fertility. We believe these powerful symbols were an important part of the new ideology, helping to unite people of different heritage.

Archaeologists also find evidence of significant and extensive trade in obsidian during the Salado florescence. People used this volcanic glass to make tools and arrowpoints.

Kayenta immigrants and their descendants probably organized obsidian trade across much of the southern Southwest. In the late 1200s, Kayenta people joined a settlement near a group of obsidian sources in what is now Mule Creek, New Mexico. That settlement grew into a major Salado community with far-reaching social and economic ties. When a site has numerous artifacts made from Mule Creek obsidian, we can infer that settlement was somehow involved with this network—and, by extension, with Salado.

Other material evidence associated with Salado varies across the landscape. An example is large aboveground structures, which people built with a variety of techniques and materials, including stone masonry and adobe.

Why is Salado important?

Salado ideology brought local and immigrant groups together. By studying Salado, we seek to understand how people of diverse backgrounds come to think of themselves as one people, while still retaining a sense of their own heritage—just as many Americans celebrate the traditions and homelands of their ancestors. Through Salado, we can examine how people maintain and transform their traditions and beliefs far from their homelands, across generations, or in the face of social and economic challenges. We can also consider what tangible evidence “heritage” leaves.

What is happening to Salado sites and Salado artifacts?

So much of what Archaeology Southwest is learning about Salado comes from our work with private landowners and other stakeholders, with whom we design and implement flexible, case-specific site protection strategies and low-impact research designs. We also make extensive use of artifacts and archives already in museums, and we advocate for continued preservation of these collections.