- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Celebrating a Mammoth Dust-Up in Bluff

San Juan County is no stranger to controversy. A divisive and tragic bust of archaeological looters took place in Blanding between 2007 and 2009. In 2014, a group of fed-up locals followed a county commissioner on an illegal “protest ride” through a popular canyon east of Blanding and Monticello that may or may not wind up being classified as a roadless area. And of course the battle for Bears Ears is still far from over…

This story is about a different kind of controversy.

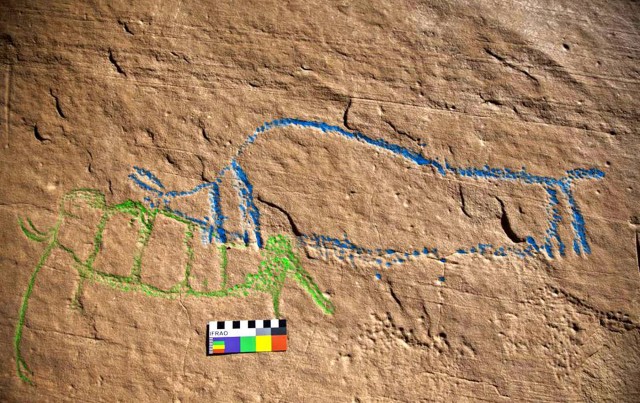

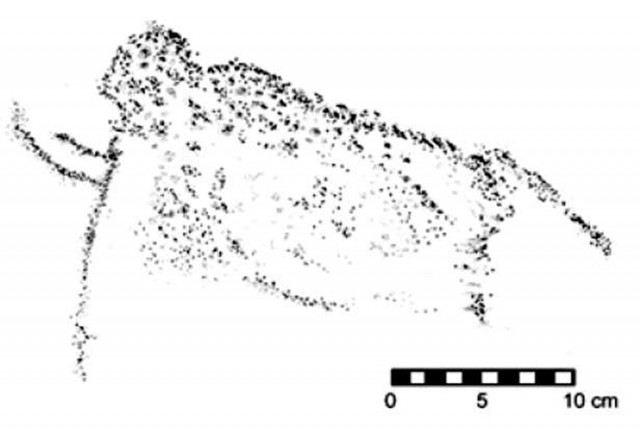

In the early 1990s, after assisting Crow Canyon Archaeological Center researchers in recording the Sand Island rock art site near Bluff, Utah, local artist Joe Pachak made a mammoth discovery. He’d spotted what he believed to be a petroglyph depicting a Columbian mammoth, one of two species of wooly mammoth formerly endemic to North America and arguably the older of the two, superimposed with what also appeared to be a Pleistocene bison.

The only other depiction of Pleistocene megafauna in the entire state of Utah is the so-called Moab Mastodon two hours to the north, and a lot of researchers view it with skepticism. Pachak knew he was onto something big, and radioed Northern Arizona University linguistic anthropologist and rock art specialist Ekkehart Malotki to come and investigate. In 2011, Malotki published his conclusions that the panel does indeed depict a Pleistocene mammoth and bison, dating to about 13,000-11,000 years ago.

Bluff rejoiced. Briefly. It didn’t take long for dissent to materialize.

The Pleistocene officially ended on 12,700 BP. Documents were drawn up and signed, or something—I don’t know. But meanwhile most of the eponymous Pleistocene megafauna had already died out by that point, including mammoths. Experts are uncertain as to the role humans may have played in this massive extinction, if indeed they played any role at all, owing to the coincident timing of the peopling of the Americas (and other continents) right as most or all of the “mega-” genera vanished. Competitive exclusion has been suggested, as has overhunting, volcanoes, and asteroids.

Whatever the case, the last reliably dated mammoths clock in at 12,200 years ago in New York and just over 13,000 years ago in the Midwest.

The only known cultural complex to have overlapped with Pleistocene mammoths in North America is the Clovis tradition, named for an iconic fluted type of projectile point first discovered near Clovis, New Mexico. Thus, it is worth noting that the earliest—and arguably still most relevant—Clovis site ever found on the northern Colorado Plateau to have temporally diagnostic artifacts was found on Lime Ridge, just a few miles west of Sand Island along the San Juan River corridor. First discovered by archaeologists working for Abajo Archaeology in the mid-1980s, the Lime Ridge Clovis site has been re-investigated several times over the past several decades, yielding a wealth of information about Paleoindian lifeways in the Bluff area and the Colorado Plateau as a whole.

But that doesn’t necessarily clinch the deal, either. Because some of the earliest confidently-dated Clovis projectile points were found between the ribs of large mammals, it was long assumed that Clovis peoples were big-game specialists, if not actually mammoth specialists, despite the economic unlikelihood of making a living that way. Museum dioramas still depict Clovis peoples as obligate mammoth killers. More recent re-investigations of the total Clovis site assemblage demonstrated that Clovis tools were correlated with “hunted” (if not scavenged) large game animals in only 14 known cases. Given that the Clovis tradition lasted for roughly half a millennium, and taking the archaeological record at its word, that’s an average of a little over two successful kills per hundred years. If Clovis peoples really were mammoth specialists, they have much to teach us about metabolism.

Meanwhile, petroglyph panels and sites with only surface assemblages of stone tools are both notoriously difficult to date, for the obvious reason that there’s nothing on them to date. Neither chert tools nor abraded sandstone surfaces offer anything in the way of corroborative strata, let alone materials that might be subject to radiometric dating methods like 14C. Thus, although the Lime Ridge site is undoubtedly Clovis, it is altogether impossible to assign it a confident date. Dating the depictions at Sand Island is an even more suspect endeavor. Moreover, geologists have suggested that 13,000 years ago the San Juan River corridor hadn’t eroded downward enough to expose the panel for desert varnishing, let alone chiseling. And so on.

Local archaeologists Don Simonis, Jonathan Till, and Winston Hurst have also weighed in on the subject, all of whose opinions may be found on display in a film by Larry Ruiz called Waking the Mammoth. A particularly intriguing hypothesis has been advanced by Hurst, who remains agnostic but hopeful, which suggests that the timing doesn’t matter as much as we think it does because people may well have been depicting something they’d been describing to each other for ages. The notion of “cultural memory” is one in which important or sacred images, stories, and songs are so vividly passed along that they can yield accurate depictions many generations after they’ve disappeared from practical appearance. Which makes sense—I, for example, live in a largely Christian nation, and although I’d never seen a live camel or an actual manger before the invention of the Internet, I could certainly have told you what they looked like. Celebrated author Craig Childs has also chimed in, in his case defending the mammoth’s authenticity in Ruiz’s documentary and a number of public appearances since then. And so on.

(For more on the above, see Malotki 2012.)

Similar disagreements among academics can be downright bloodthirsty, as in the classic cases of Lewis Binford versus François Bordes or Napoleon Chagnon versus Muckraking Lunacy. For the most part, however, the Bluff mammoth debate is not overly staffed with academics. Joe Pachak is a professional artist. Larry Ruiz makes films. Don Simonis is a BLM archaeologist with an unusually genial view toward the public. Winston Hurst and Jonathan Till are prolific field investigators who are downright notorious for being helpful and nice. Craig Childs is an author and adventurer with a big smile and a friendly handshake. I could go on. So while academics are certainly involved in the matter, and likely always will be, the debate was never a purely academic one. This might explain why nobody was carted off the battlefield with a gaping neck wound.

In honor of both the supposed mammoth and bison images themselves, and the curious little controversy that came to swirl around them, the 2012 Bluff Arts Festival featured a workshop led by Pachak and some friends on how to construct a life-size mammoth out of natural building materials. On the night of the Winter Solstice, joined by an impressive crowd of revelers from the local and surrounding communities, they festively burned it to the ground.

It was heralded as a lovely and historic event, so much so that Pachak and his artistic colleagues were compelled to do it again the following year. They did it yet again in December of 2014, this time deciding to shake things up a bit by erecting an enormous Pleistocene bison instead of a mammoth (Bison antiquus being the presumed second cast member in the controversial rock art).

And again the thing was burned to the ground on the Solstice, to the delight and dancing of many.

In the winter of 2015–2016, no giant anything was burned in downtown Bluff. It seemed that Pachak and the mammoth dust-up were over. Just as days in the belly of the Bears Ears seem their darkest, however, a fire shall be lit again: Pachak and Co. have agreed to erect and burn a fourth gigantic brush-and-bramble structure, this time a pair of San Juan River herons.

With one day to go, Bluff is gearing up for a behemoth of a burn. Eager revelers have booked most of the local motels to capacity. Even without the mammoth controversy having ever been completely and satisfactorily resolved, we’ve frankly got a lot to burn about—the future of Bears Ears and of conservation more generally is on everyone’s minds.

Join us if you can!