- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Greater Bears Ears as Borderlands

Today’s post is by our friend and frequent contributor R. E. Burrillo, who co-edited, with Benjamin A. Bellorado, the new issue of Archaeology Southwest Magazine, “Sacred and Threatened: The Cultural Landscapes of Greater Bears Ears,” released today.

(March 2, 2018)—In traditional parlance, a “frontier” is a region at the edge of a settled area—leaving some allowance for definitions of the word “settled.” The closing of the American frontier supposedly took place in or around 1890, when Teddy Roosevelt’s Boone and Crockett Club started earning national recognition for advocating on behalf of resource conservation and cessation of the rampant and unregulated expansionism of the previous century. Forests and rivers and minerals and animals were not, it turned out, inexhaustible; and intelligent, scientifically informed management of our shared material heritage was imperative.

Roosevelt took over as President of the United States a little over a decade later, following the assassination of McKinley, and would be formally elected to the position in 1904 with 66 percent of the vote—losing only in the South because he’d had the temerity to host an African-American, Booker T. Washington, at his dining table. Two years later, Roosevelt signed into law the Antiquities Act, codifying an aggressive and impressive standard in terms of which future presidents could enact his era’s ideals about responsible management of resources.

But the closing of the American frontier was never a full and final act. For one thing, some groups of citizens in the West continue to rail against the very concept—let alone the practice—of centralized and formalized management of resources, believing instead that presence is tantamount to ownership and that the Homesteading Era never really ended. For another, traditionally marginalized or disenfranchised groups in the West—throughout the country, in fact—similarly rail against the idea that they enjoy equal representation in the decisions being made on both the local and federal levels vis-à-vis their livelihoods and the landscapes they hold most dear.

The American frontier remains, in other words, unsettled. And it is in such frontier settings, the peripheral or borderlands areas, that some of the greatest and most intriguing cultural phenomena in all of human history may be found. This axiom is epitomized in the Bears Ears area of southeastern Utah, and is amply demonstrated in the latest issue of Archaeology Southwest Magazine, appropriately titled “Sacred and Threatened: The Cultural Landscapes of Greater Bears Ears.”

Starting with the Archaic period (ca. 6,000 B.C.–A.D. 500), when the post-Pleistocene climate shifted toward more aridity and seasonality, hunter-gatherers from throughout the surrounding Colorado Plateau and eastern Great Basin region converged on the Bears Ears area to settle and forage in higher-altitude settings than during the preceding Paleoindian period. According to Don C. Irwin—Manti-La Sal National Forest district archaeologist for nearly the past two decades—this has resulted in a co-occurrence of diagnostic stone tools from the Southern (or Oshara) and Northern Colorado Plateau artifact traditions in at least the Dark Canyon region, as discussed in his article in this issue. This is the first clear evidence of groups from different cultural zones commingling in the borderlands area of the Bears Ears landscape, and it sets a lasting precedent.

During the late Basketmaker period (ca. A.D. 500–750), which is discussed in our issue by Jonathan Till, the Bears Ears area formed a frontier between the heart of the Fremont occupation zone to the north and that of the Northern San Juan branch of the Ancestral Pueblo area to the south and west. Although the border between the Pueblo and Fremont worlds was often “closed,” there was enough permeability to allow a commingling of culture-material traits that archaeologists are still trying to unravel. A suite of elements—including pottery, bean agriculture, and bow-and-arrow technology—moved between the two archaeological culture areas during this period. This opening of the Fremont–Pueblo border would occur again after about A.D. 1000–1050, according to Phil Geib in Glen Canyon Revisited, one tangible result of which is the blended Fremont and Pueblo designs at Newspaper Rock in Indian Creek.

Following the near-total depopulation of the area following the Pueblo I period (ca. 750–950), the rise and fall of the Chaco Phenomenon in northern New Mexico exerts a tremendous influence on the local culture history of the Bears Ears area in both its waxing and its waning eras. Distinguished Blanding-based archaeologist Winston Hurst has been studying this phenomenon for decades, and in this issue he presents a comprehensive picture of the articulation of the Chacoan world with the Northern San Juan communities of the Bears Ears area. Likewise, Jim Allison and Jaclyn Eckersley of Brigham Young University provide ancillary snapshots of how this picture is reflected at Red Knobs (coincidentally located right along the border of the original Bears Ears National Monument) and in Beef Basin.

During the Terminal or Pueblo III period (ca. 1150–1290), outliers from the heartlands of Mesa Verde to the east and Kayenta to the south interdigitated at Bears Ears to create a lot of unique and puzzling “Mesa-Yenta” sites with local and nonlocal artifacts and architecture. Hurst characterizes this period as the “polychrome revolution,” based on cessation of locally-produced Abajo Red Ware pottery and incursion of multicolored polychrome wares from the Kayenta or Tsegi region to the south. On a somewhat smaller scale, within the Bears Ears area, shifting demographics in the post-Chaco era prior to depopulation of the area are reflected in pottery production and exchange across the geological boundary of Comb Ridge—presented and discussed in this issue by Donna Glowacki, along with Winston Hurst and Jeffrey Ferguson.

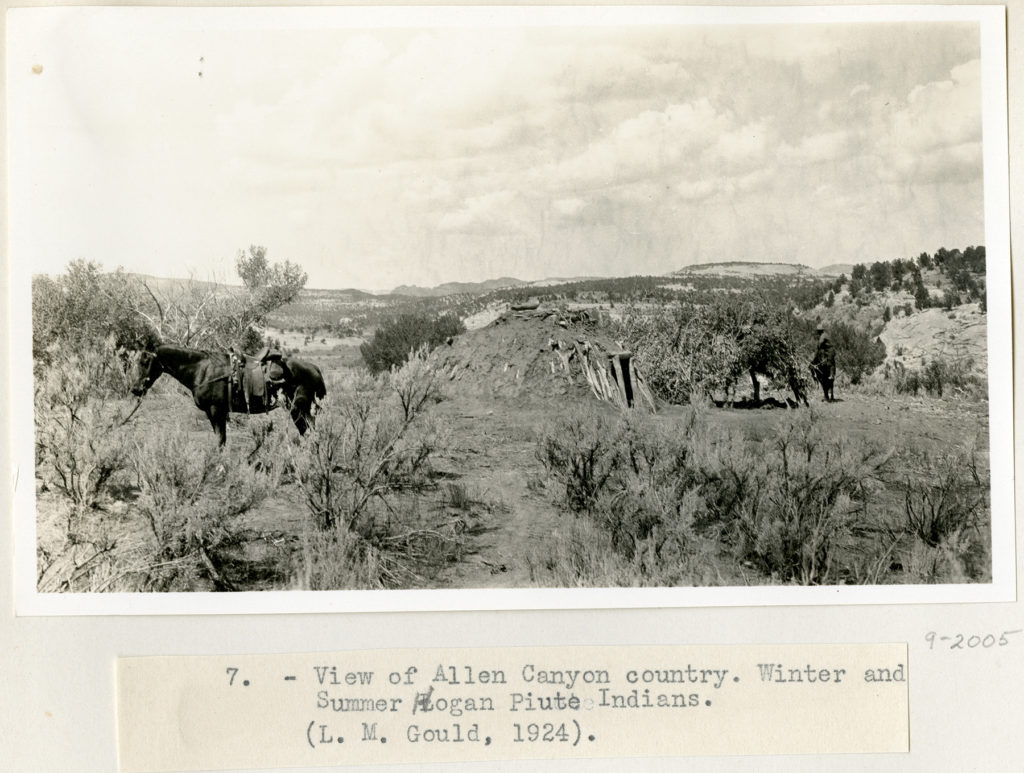

In the subsequent Protohistoric and Historic periods (1300—present), Navajos and Utes/Paiutes living outside their respective traditional homelands traded cultural elements so often, and so thoroughly, that William Henry Jackson of the Hayden Expedition wrote confusedly about a band of Weeminuche Utes with “considerable corn planted” (the Utes are traditionally non-agrarian) in Montezuma Creek in the 1870s. Continuance of this theme in the Bears Ears area has engendered difficulty in discerning between Ute or Paiute and Navajo archaeological sites, as reviewed in our issue by Jay Willian and Winston Hurst. And the appearance of Mormon and gentile cowboy settlers during the rest of the historic period—that is, post-1879—has also precipitated a tense yet dynamic cultural patchwork involving Mormon and gentile “cowboy” cultures that continues to this day, exemplified best in Fred Keller’s historic ballad “The Blue Mountain Song” (the “signature anthem” of San Juan County, which involves a rogue cowboy dancing with Mormon girls in a now-extinct saloon in Monticello).

And now, as we move by fits and starts into what might be called the Conservation, Recreation, and/or Development period (ca. 2015–?), borderlands-style cultural coalescence in the Bears Ears area shows no signs of slowing down. Indigenous traditionalists and conservationists of every stripe are working so closely together that yet another unique and distinctive Bears Ears community appears to be emerging. The formal incorporation of the town of Bluff—after 137 years of being more-or-less ignored by the Utah state legislature—closely preceding a federal court ruling against gerrymandering in San Juan County means that traditionally disenfranchised groups in the Bears Ears area may soon be getting the equal say they’ve been rightfully demanding since the supposed closing of the American frontier. At the same time, local administrators and businesspeople who oppose the heavy-handedness of national monuments are nonetheless beginning to adjust to the fact that there is simply no stopping the increasing presence of recreational tourism in what was formerly their sleepy little corner of the world.

Beginning in 2015, a coalition of five Native American tribes—the Navajo, Hopi, Ute, Zuñi, and Ute Mountain (Colorado) Ute—proposed a 2-million-acre Bears Ears National Monument to protect what they consider a sacred landscape from expansion of grazing and energy-development leases. In June 2016, exactly 110 years after creation of the Antiquities Act, an enormous crowd of citizens gathered in the not-yet-town of Bluff, Utah, to weigh in on the monument proposal. Half a year later, Bears Ears National Monument was designated by President Barack Obama, to a chorus of cheers and jeers whose echoes have yet to die away. In a move legal scholars are debating and the tribes and conservation allies are challenging in court, President Donald Trump reduced the size of the monument by more than 80 percent, into a pair of tinier monument units, one of which was given a Diné name against the intentions of the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition. The future of Bears Ears National Monument, like the spirit of the frontier borderlands that it so powerfully epitomizes, remains unsettled.

Southeast Utah is the backwoods of everywhere—a peripheral zone where cultures meet and meld into striking new patterns. In this issue of Archaeology Southwest Magazine, we have endeavored to present as many of them as possible, centering upon the pivotal focus points of archaeological research and preservation that are the core of Archaeology Southwest’s mission while creating spaces where people who hold the natural and cultural landscapes of Bears Ears most sacred can fully express their own perspectives in their own words.

Available now, Archaeology Southwest Magazine Vol. 32, No. 1, also features the photography of Jonathan Bailey and Adriel Heisey.

2 thoughts on “Greater Bears Ears as Borderlands”

Comments are closed.

Thank you for providing additional background to this discussion.

My first sight of the artist’s visualization of Bear’s Ears was “Wow! The folks who built Pipe Springs must have seen the basic design of this ruin!”

Imminently defensible, especially if the opening could be closed or narrowed.