- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Plant and Animal Use in the Mimbres

(March 22, 2018)—One thing I enjoy about working at Archaeology Southwest is the opportunities we have to share new research beyond the specialized journals where a lot of our work gets published. In that spirit, I’m happy to share an update on some recent publications from the Mimbres plant and animal legacy-data project paleoethnobotanist Mike Diehl and I have been working on—a project I blogged about back when it began.

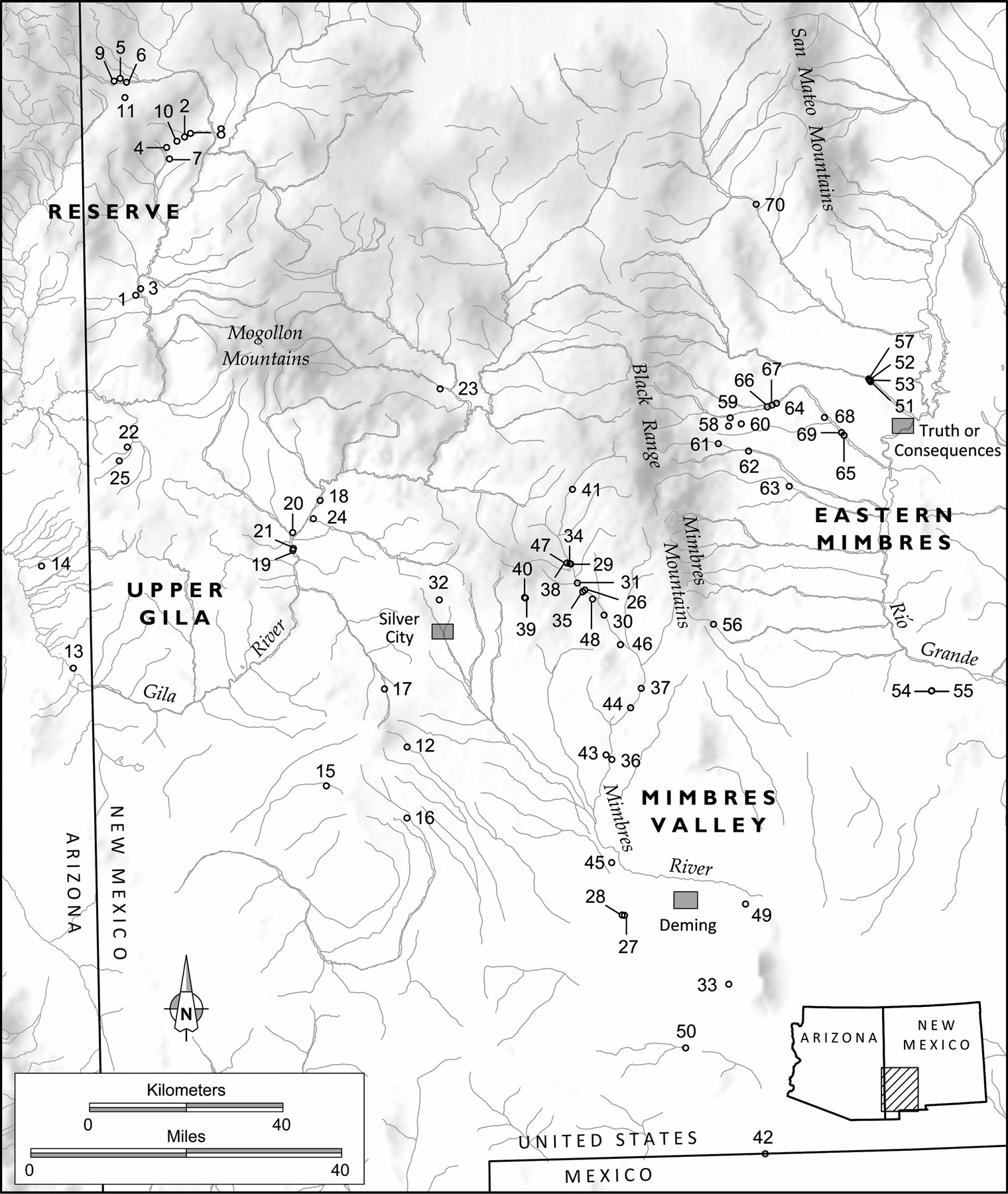

Mike and I have spent a lot of time combing through old site reports, unpublished papers, and even boxes of Xerox copies from a colleague’s garage in order to build a database of all the Mimbres region plant and animal data we can find. Fortunately, we have a lot of great colleagues who helped us track those datasets down, and a great volunteer, Jaye Smith, who contributed many hours of computer data entry time to get some of the faunal datasets into a more permanent, accessible form. Mike and I have also identified the burned seeds, wood, and animal bone in previously unanalyzed collections from several older excavations in the region. We now have animal bone data from 96 assemblages (collections of bones from a specific time period within an archaeological site). We’ll be working on what the plant and animal datasets together might tell us over the coming months. The animal data are already providing some interesting information.

One of the immediately useful results of this effort has been a complete list of sites in which various animal species have been found. This provides information about how the ranges of species have changed over time in the study area. Several other projects in the Southwest take a similar approach for broader regions (including FAUNAZ and Neotoma), but our project has devoted considerable effort into tracking down as many older datasets as possible for our specific study area and then examining them for detailed information on dating, context, and the reliability of identifications.

I was lucky to meet Steve MacDonald, a retired mammalogist, at our Preservation Archaeology Field School, which takes place near his home in Gila, New Mexico. We soon started exchanging excited emails about topics only a very specific kind of kindred spirit could get excited about. (“Wow, did you know there were muskrats on that drainage?” “Hey, look at this possible jumping mouse identification!” “Ugh, mollusk taxonomy makes my head spin!”). After a few months of this, we began collaborating to summarize these occurrence data in ways we hope will be useful to biologists and archaeologists.

Our work thus far is summarized in a poster we presented at the 2017 Society for American Archaeology meetings and at the recent 2018 Natural History of the Gila Symposium. We hope this will help zooarchaeologists become more aware of when animals we identify in a site assemblage are outside their expected ranges, so we might discuss their identifications in greater detail in our reports, and so we might highlight occurrences that will be of interest to zooarchaeologists in other regions and to biologists. For biologists, this ongoing work summarizes archaeological data in a more accessible form than the many “gray literature” reports where much of it is currently discussed, and it will provide references to those original reports so researchers can find them more easily.

This research also suggests some interesting changes in animal distribution related to human activities, including hunting and vegetation changes caused by activities such as farming and wood gathering. Several species have changed in surprising ways. For example, beaver are almost unknown in the faunal record from the Mimbres Valley (only two incisors are known), but are often depicted on Classic Mimbres bowls. They’re also absent from the historic record in that valley, but are present there today. Why are they so uncommon in the past? Were they absent until recently? And if so, how did they get there? Other species whose archaeological distributions differ from today’s known ranges include prairie dogs, muskrats, and the yellow-faced pocket gopher.

Other interesting patterns are more specific to archaeology, but still have interesting broader implications for understanding how humans affect animal resources. In general, animals less resilient to human hunting and landscape changes (such as tasty hoofed mammals and the large carnivores that like to eat them) are much less common in the archaeological record than small, fast-breeding animals that do well in weedy vegetation (such as rabbits and rodents). Comparing a large number of bone assemblages from many sites through time shows that although less-resilient animals were quickly reduced during periods of higher human population in the past, those animal populations also recovered when fewer humans were present. Animals like deer were particularly rare during the Classic Mimbres period (A.D. 1000–1130), when human populations were highest in much of the study area. By the 1300s, however, many more deer bones are present in archaeological sites. Deer populations probably recovered locally during the 1200s, when very few farmers lived in the area. They may also have been less heavily impacted by human activities in the large villages of the 1300s, if—as some archaeological evidence suggests—people in those villages moved from place to place more often.

Some of my earlier work on animal population recovery suggested similar patterns, so I was happy to see them borne out with a more fine-grained dataset. To me, this is an exciting result, as it shows humans may hunt for many centuries without extirpating important animal populations when conditions are right, and heavily impacted animals may sometimes recover from the pressures a large human population placed on them even when smaller numbers of meat-loving farmers are still around to eat them.

You can download my research poster here (opens as a PDF). If you want all the details (and graphs!) about the research in the second half of this blog and don’t mind archaeological jargon, the first 50 interested people can download our 2018 Kiva article free here. Thanks to Mike Diehl and Steve MacDonald for being so much fun to work with, and thank you to the National Science Foundation (BCS-1524079) for funding this research. Social science research helps us understand the world better every day.