- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- What’s in a Notch?

(March 28, 2018)—Projectile points were important tools for hunting and weaponry. They might have served a social function, as well, as suggested by occasional elaborate designs or placement in ritual deposits. We study points because they may be reliable chronological markers, and because they may hold information about social interaction, migration, and technological traditions. Studies of this nature have often yielded successful results, including those that involved pre-Classic Hohokam points (circa A.D. 750–1150) in southern Arizona.

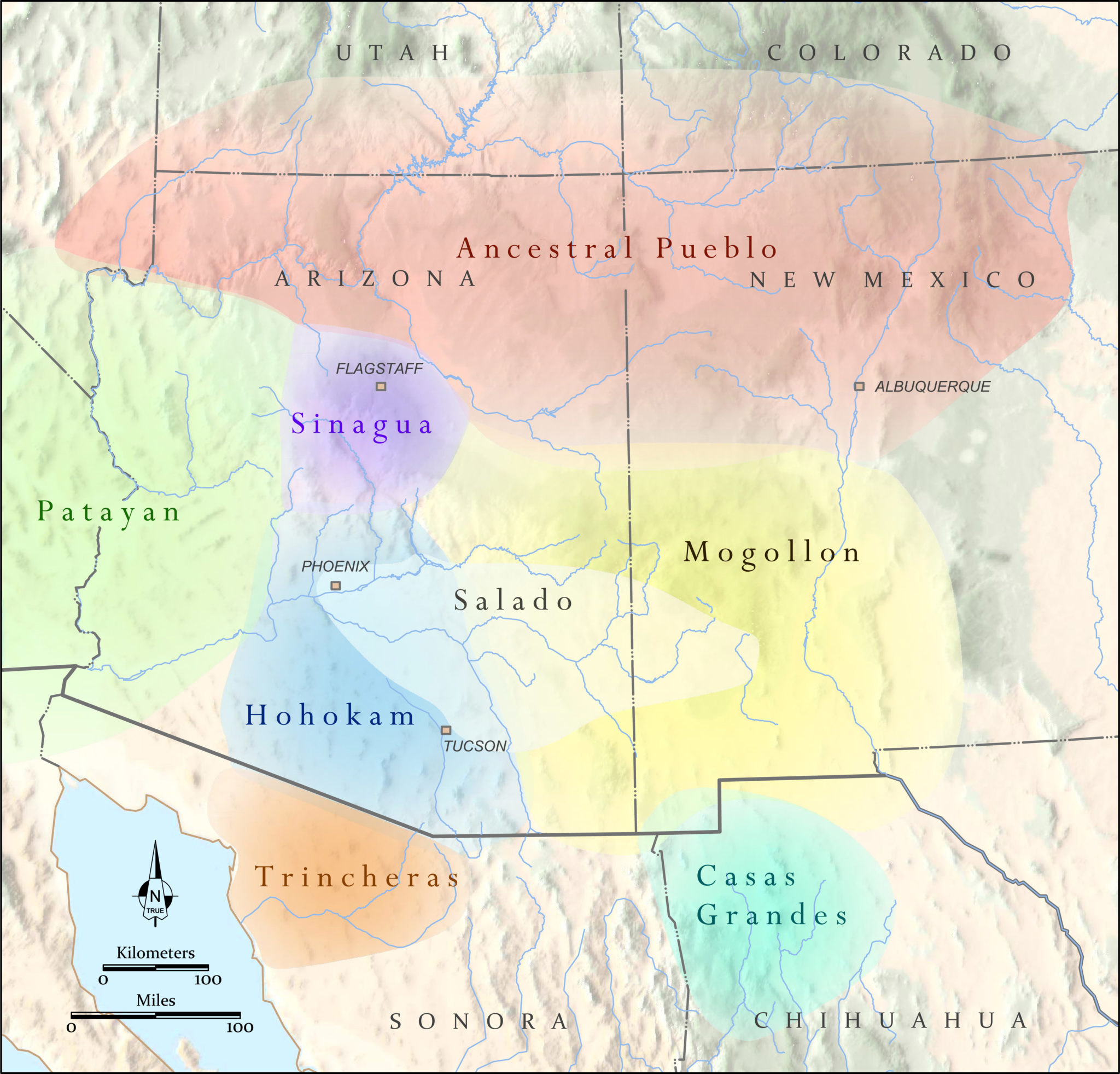

My master’s thesis research focused on arrow points made during the Classic period (A.D. 1150–1450), a time when considerable changes were taking place in southeastern Arizona. The region experienced two waves of migrations: people from the Mogollon Highlands (the southern edge of the Colorado Plateau in what is now central and eastern Arizona) moved into the northeastern Tucson Basin during the early Classic period, and then groups from the Kayenta region in the Four Corners area arrived in the lower San Pedro valley in the late 1200s. These patterns have been well documented through grant-funded projects, field school excavations, and cultural resource management work, and researchers have explored how local and migrant groups responded to each other, formed new communities, and developed new shared traditions—those that we recognize as Salado culture. Pottery designs, architecture, and the obsidian trade all provide evidence of changing dynamics during the Classic period. One of my goals was to identify how these changes may have influenced the design choices people made during projectile point production.

Both unnotched and side-notched points are common during the Classic period. Until about 1300, toolmakers placed side notches near the mid-point of the blade. After that time, they preferred lower, deeper notches. Lower notch placement would have increased the length of the blade edge that extended past the sinew wrapping that attached it to the arrow shaft, and the deeper notches may have provided a more secure haft. People across the Southwest continued to use unnotched points for several centuries.

Although similar point types are found across a wide swath of the Southwest during the Classic period, we needed a systematic study to determine whether point designs were different in areas where migrant groups settled or at sites with blended cultural traditions. Certainly, I thought, an analysis of more than 600 points from 26 sites using metric data, qualitative data, and statistics would tease out these differences—but, for the most part, it did not! And I learned to appreciate the value of negative results.

Similarities in point types at sites in the Tucson Basin suggest that people from different areas with different pottery-making traditions were likely using common point types as early as the late 1100s, when Mogollon groups arrived in the area. Design differences were also lacking at late Classic sites in the San Pedro valley with migrant enclaves, and this may be attributed to the expansion of social networks during this time.

I did find some variation, though, among sites in the northwestern Tucson Basin where there is little evidence of migrant groups. Several points have wider, deeply concave bases and pointed ears—attributes that would not be visible once the point was inserted into the arrow shaft. This may reflect differences in learning traditions, or what are sometimes referred to as “communities of practice.” Communities of practice are social groups with shared knowledge and traditions that are formed through active participation in their community. Learning within these communities is often in an informal setting among people familiar with one another.

In the example of projectile point production, people may have been copying what they saw during their learning process while crafting stone tools with their group. In this way, they were still making the preferred or socially accepted projectile point forms, but the base shape reflects different learning traditions or group preferences.

It would have been exciting to identify a point type, or a specific point attribute, introduced by migrant communities, and there are still some avenues of research to be explored by widening the dataset. In the meantime, I learned that similar point designs were used by groups living in separate areas and with different cultural influences, providing yet another view of the ideas shared and connections made during the Classic period.

Explore the News

Related to This

-

Culture Hohokam

-

Culture Mogollon

-

Culture Ancestral Pueblo

-

Project San Pedro Ethnohistory Project