- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Identity Politics, Past and Present

(August 7, 2018)—Social identity has emerged as a field of concerted archaeological inquiry in the Southwest and beyond. At Archaeology Southwest, we’ve been thinking a lot about how people create and express social identities at multiple scales, and how we can see those choices within the material record we find so fascinating. Our Fluid Identities research program is looking at the Big Picture of social identity within an appropriately large frame—the Gila River watershed, which stretches from the highlands in southwest New Mexico across southern Arizona before spilling into the Colorado River at Yuma and very near its delta at the Gulf of California.

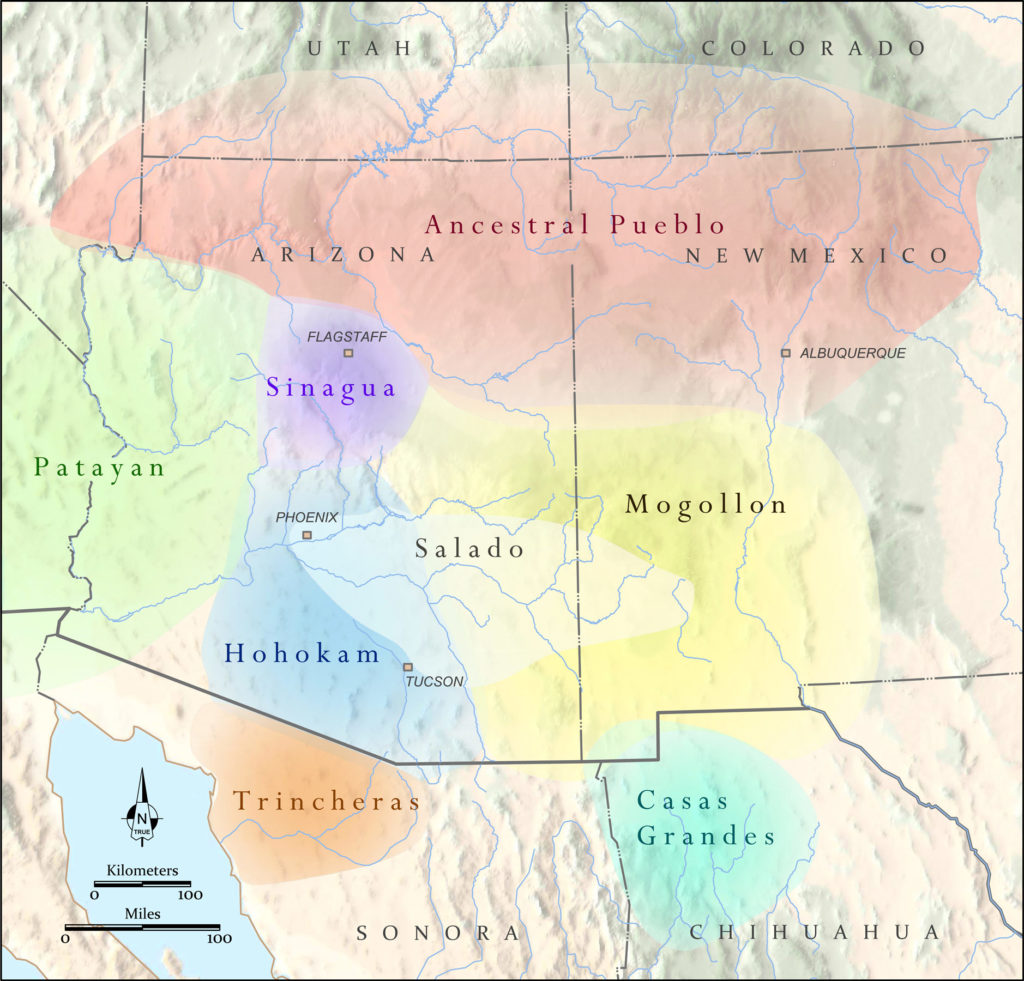

The Gila was integral to three ceramic-period archaeological traditions we refer to as Mogllon (including Mimbres), Hohokam, and Patayan. Interestingly, these traditions were tethered to different zones of elevation: Mogollon and Mimbres in the upper Gila, Hohokam in the middle, and Patayan at the lower end. This regional division just so happens to correspond with staff research interests and expertise. Karen Schollmeyer works in the upper Gila, with active research programs including the Preservation Archaeology Field School. For her dissertation, Leslie Aragon is looking at the intersection of social identity and the Hohokam ballcourt network along the middle course of the Gila. I’m picking up the tail end with my various research projects at Painted Rocks, the Maricopa Mountains, and Bouse, as well as through the collaborative Lower Gila Ethnographic and Archaeological Project. In the late 1200s, the Salado phenomenon broke through the elevational divide, as it spread among communities in the upper and middle zones of the Gila. This is the purview of Jeff Clark, who is increasingly seeing this as a religious moment and movement in which people of different social backgrounds and identities suddenly bought into a new, socially inclusive ideology.

Our collective research is important because we’re not simply interested in bounding social identities in time and space, as was popular (and arguably necessary) during archaeology’s early preoccupation with defining culture areas. Instead, we’re looking at this anthropologically, and quite like the way people talk about identity politics today—identity as a social strategy rather than a rigid category. How did people in the past express, alter, and manipulate their identities in relation to others or new circumstances, and why did they choose to do so? Our Fluid Identities program is exploring how these issues played out along the Gila River 1,000 years ago, just as they do today.

Interesting parallels may be drawn between the social tensions that arose when Ancestral Pueblo immigrants moved into Hohokam territory of the lower San Pedro River valley in the late 1200s, and the crossing of the U.S./Mexico border by immigrants and asylees from Latin American countries in the 21st century. At the heart of both migrations was and is the need to escape deteriorating conditions in one’s home country in order to ensure a future for themselves and their families. In the archaeological case, suspicion and unrest gave way to cooperation and development of an ideology of inclusion accompanied by a remarkable aesthetic, and possibly a new or revitalized religion (i.e., Salado). Might the contemporary case play out in a comparable way?

The welcome lesson from the past is that sometimes these identity politics were far from antagonistic. The lower Gila, for instance, saw the cooperative coexistence of people of different backgrounds, traditions, languages, and religions for nearly a millennium. Between AD 1000 and 1400, the material culture of this region shows a mosaic and blending of Hohokam and Patayan traditions. It seems that at first, family units expressing a Patayan cultural identity—presumably migrants from the west—took up residence near established Hohokam villages. At the site of Las Colinas in Phoenix, researchers 30 years ago reported on what they interpreted as a Patayan enclave within a Hohokam village around AD 1050.

Las Colinas was not an anomaly. From more recent work in the vicinity of Gillespie Dam along the lower Gila, we believe that by the 1000s, some villages were multicultural or multiethnic, with people living in the same community yet maintaining distinct cultural traditions reflecting what we see as Patayan or Hohokam identities. This pattern of multicultural co-residence along the lower Gila persisted into the historic period, as the journals of Spanish and Mexican explorers chronicle accounts of passing through villages comprised of O’odham and Yuman speakers. And it continues today, with the Akimel O’Odham and Piipaash (Yuman speakers) residing together within the Salt River Pima-Maricopa and Gila River Indian Communities, all the while maintaining unique social identities and distinct traditions.

The archaeology of identity politics is not merely a topic of antiquity, as it very much factors into the contemporary political and social landscape as well. Sadly, archaeology and contemporary identity politics have a troubling past. Recent history is replete with scenarios of fascist regimes relying on biased or bogus archaeological interpretations to elevate senses of nationalism, often at the expense, detriment, or exploitation of “others.” Impacts ranged from the harmful exclusion from power to outright genocide. The United States was hardly immune to this. The early days of American archaeology witnessed educated and powerful white men claiming the numerous earthworks in eastern North America to be the works of the lost tribes of Israel or Asiatic migrants. It was untenable to think they had been made by the American Indians living there at contact. For these early scholars—themselves descendants of European immigrants—Western mythology was more attuned to their notions of social evolution than the simplicity of Occam’s razor. Such ignorance, often willful, served to disenfranchise descendant American Indian communities, many of whom were rounded up and expelled from their traditional lands.

That may seem like a distant and alien past, but the influence of archaeology in contemporary identity politics persists. Indeed, the courts regularly entertain archaeological interpretation when they hear cases involving American Indian claims to or pleas for the preservation of ancestral lands, water sources, sacred places, or traditional plant and animal resources. Scholarly papers and professional opinions are often introduced as evidence in such proceedings. For example, ethnographies and archaeological reports, penned by white scholars of course, were the principal evidentiary items in the Indian Claims Commission (ICC) hearings. Those midcentury proceedings, ostensibly intended to make amends for displacing millions of American Indians, resulted in the “quieting” of otherwise murky federal government title to aboriginal lands through pennies-on-the-dollar payments to tribes for the true value of their homelands. The commission simply could not take American Indians at their word, and as a result many regard the commission’s findings as a sham.

This insistence on a perceived archaeological objectivity persists. In cases regarding the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), for instance, the courts weigh professional archaeological interpretation alongside other lines of evidence, such as linguistics, genetics, and oral histories, when evaluating tribal claims to items of cultural patrimony. At times, professional archaeological interpretation contradicts with these other lines of evidence, and may actually be at odds with tribal interests and claims. While ICC and NAGPRA represent good-faith efforts to rectify historic injustices against indigenous people, they also represent a system that, in some instances, still privileges archaeological interpretation of American Indians over American Indian voices and interests. The recent stand-off at Standing Rock echoes this imbalance.

Although archaeologists study the past, what they choose to study, how they interpret the data, and the manners in which they present their findings can have profound impacts on peoples’ lives today. Writing papers about others’ ancestors is not simply an academic practice. To borrow a phrase from the Miranda warning, what we say and write may be used against others in a court of law. If we respect the people we study who can no longer speak for themselves, and if we respect their descendants, then it behooves us to acknowledge the power of this discipline, forecast the potential impacts our interpretations may have on living people, and act and write accordingly. This is an ethical imperative and a moral obligation that comes with the territory and privilege of being a scholar of the past. Archaeology and the interests of descendant communities are only incompatible if we make them so.

Explore the News

Related to This

-

Project Fluid Identities

-

Culture Pataya

-

Culture Hohokam

-

Culture Ancestral Pueblo

-

Culture Mogollon