- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Celebrating a Mammoth Dust-up in Bluff (2018 Editi...

(December 4, 2018)—This is an update of an essay I posted here in December 2016. Bluff artist Joe Pachak and the gang are preparing for another Winter Solstice festival, and meanwhile a lot else has happened between then and now.

Utah’s San Juan County is no stranger to controversy. A divisive and tragic bust of archaeological looters took place in Blanding between 2007 and 2009. In 2014, a group of fed-up locals followed a county commissioner on an illegal “protest ride” through a popular canyon east of Blanding and Monticello that may or may not wind up being classified as a roadless area. And of course the battle over Bears Ears National Monument is still far from over.

The monument was officially created on December 28, 2016, just eight days after my original essay was posted. Almost exactly a year later it was slashed by 85 percent by the sitting president in response to pressure from the Utah delegation. Lawsuits swiftly followed, including that of Archaeology Southwest and co-plaintiffs Utah Diné Bikeyeh, Patagonia Works, Conservation Lands Foundation, Friends of Cedar Mesa, Society for Vertebrate Paleontology, Access Fund, and National Trust for Historic Preservation.

This is the story of a slightly more prosaic controversy.

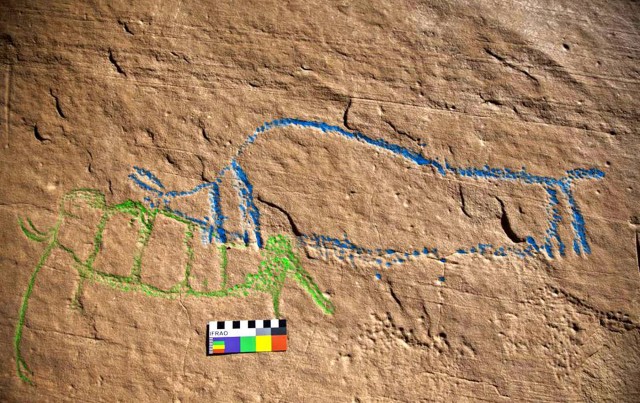

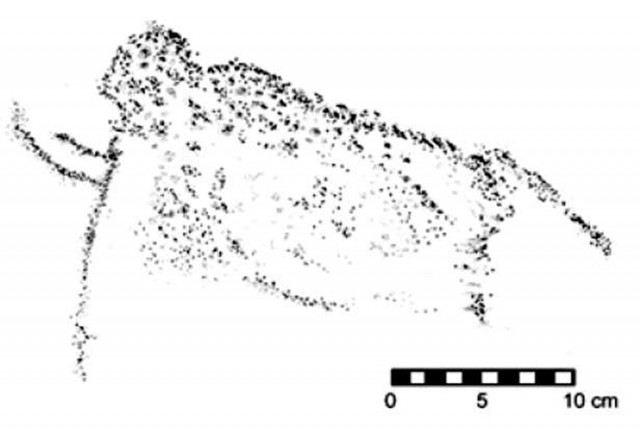

In the early 1990s, after assisting Crow Canyon Archaeological Center researchers in recording the Sand Island rock art site near Bluff, Utah, local artist Joe Pachak spotted what he believed to be a petroglyph depicting a Columbian mammoth, one of two species of wooly mammoth formerly endemic to North America and arguably the older of the two, superimposed with what also appeared to be a Pleistocene bison.

The only other depiction of Pleistocene megafauna in the entire state of Utah is the so-called Moab Mastodon two hours to the north, and a lot of researchers view it with skepticism. Pachak contacted Northern Arizona University linguistic anthropologist and rock art specialist Ekkehart Malotki to come and investigate. In 2011, Malotki published his conclusions that the panel does indeed depict a Pleistocene mammoth and bison, dating to about 13,000–11,000 years ago.

Bluff rejoiced, for a short time.

But it didn’t take long for dissent to materialize. The last reliably dated mammoths clock in at 12,200 years ago in New York and just over 13,000 years ago in the Midwest. There are no other known cases of mammoth petroglyphs anywhere in North America.

The only known cultural complex to have overlapped with Pleistocene mammoths in North America is the Clovis tradition, named for an iconic, fluted type of projectile point first discovered near Clovis, New Mexico. Thus, it is worth noting that the earliest—and arguably still most relevant—confidently dated Clovis site on the northern Colorado Plateau is the nearby Lime Ridge Clovis Site.

First discovered by archaeologists working for Abajo Archaeology in the mid-1980s, the Lime Ridge site has been re-investigated several times over the past several decades, yielding a wealth of information about Paleoindian lifeways in the Bluff area and on the Colorado Plateau as a whole. So there was at least some human presence in the greater Bluff area during the time when people were presumed to have been mammoth hunters.

But that doesn’t necessarily clinch the deal, either. Because some of the earliest confidently dated Clovis projectile points were found between the ribs of large mammals, it was long assumed that Clovis peoples were big-game specialists, if not actually mammoth specialists, despite the economic unlikelihood of making a living that way. Museum dioramas still depict Clovis peoples as obligate mammoth killers. More recent re-investigations of the total Clovis site assemblage demonstrated that Clovis tools were correlated with “hunted” (if not scavenged) large game animals in only 14 known cases. Given that the Clovis tradition lasted for roughly half a millennium, and taking the archaeological record at its word, that’s an average of a little over two successful kills per hundred years. If Clovis peoples really were mammoth specialists, they have much to teach us about metabolism.

Meanwhile, petroglyph panels are notoriously difficult to date, for the obvious reason that there’s nothing on them to date. Abraded sandstone surfaces simply do not offer anything in the way of corroborative strata, let alone materials that might be subject to radiometric dating methods like 14C. Thus, although the Lime Ridge site is undoubtedly Clovis, it is nearly impossible to assign it a confident date. Dating the depictions at Sand Island is an even more suspect endeavor. Moreover, geologists have suggested that 13,000 years ago the San Juan River corridor hadn’t eroded downward enough to expose the panel for desert varnishing, let alone chiseling. And so on.

Local archaeologists Don Simonis, Jonathan Till, and Winston Hurst have also weighed in on the subject in a variety of public forums. A particularly intriguing hypothesis has been advanced by Hurst, who remains agnostic but hopeful, which suggests that the timing doesn’t matter as much as we think it does because people may well have been depicting something they’d been describing to each other for ages. The notion of “cultural memory” is one in which important or sacred images, stories, and songs are so vividly passed along that they may yield accurate depictions many generations after they’ve disappeared from practical appearance.

For more on the above, see Malotki 2012.

In honor of both the supposed mammoth and bison images themselves, and the curious little controversy that came to swirl around them, the 2012 Bluff Arts Festival featured a workshop led by Pachak and some friends on how to construct a life-size mammoth out of natural building materials. On the night of the Winter Solstice, joined by an impressive crowd of revelers from the local and surrounding communities, they festively burned it to the ground.

It was heralded as a lovely and lively event, so much so that Pachak and his artistic colleagues were compelled to do it again the following year. They did it yet again in December of 2014, this time deciding to shake things up a bit by erecting an enormous Pleistocene bison instead of a mammoth (Bison antiquus being the presumed second cast member in the controversial rock art).

And again the thing was burned to the ground on the Solstice, to everyone’s delight. In the winter of 2015–2016, no giant anything was burned in downtown Bluff, and then the event resurfaced—this time featuring a pair of San Juan River herons.

The 2017–2018 version featured a pair of dancing bears, which some people unfortunately misinterpreted as a statement about the “Bears” part of Bears Ears National Monument. In fact it was emblematic of the sacred Bear Dance of the Ute people—which was actually explained via loudspeaker by a member of the Ute Mountain Ute tribe before they were set ablaze.

Although the Ute Mountain Utes are indeed among the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, their participation in the event wasn’t about the monument so much as what Coalition founding member Eric Descheenie once called—in an excellent documentary by Angelo Baca—one of its bedrock principles: the creation of a truly multiethnic community. A look at the diversity of attendees over the years gives the strong impression that this goal stubbornly fluoresces.

This year the flammable avatar is a coyote, which engenders some amusing follow-up observations.

For one: Coyote is the trickster in the cultural narratives of a vast number of Native American tribes, including the Navajo, two of whom were just elected to the San Juan County Board of Commissioners—making the commission finally reflect the makeup of the place itself! The Hopi have their own assortment of coyote stories, as do the Zuni and the Ute, making it a shared theme for the Bears Ears area and the tribes that consider it part of their cultural geography.

For another: scientifically speaking, coyotes have reacted to eradication efforts in an almost laughable manner. Coyotes are actually evolved to increase their birth rates whenever their population feels pressured, and the ways in which they detect and measure such pressures is amazing. They use their iconic yips and whines as a sort of local census. If those calls aren’t answered—or are answered very weakly—by nearby packs, it actually triggers an autonomic response that produces larger litters. This isn’t true of other major American predators like grizzly bears, wolves, or mountain lions, which is why historic efforts to eradicate them from the continental U.S. have worked so well that all three are entirely gone from much of their ancestral territories (you’ve got this to thank next time you swerve madly around ten deer in a row). But coyotes are different, biological tricksters indeed, and because of this every effort to wipe them out has thus far resulted in more coyotes than ever.

Meanwhile, at their newly opened Bears Ears Education Center, local conservation advocacy and stewardship group Friends of Cedar Mesa is planning a day of fun activities to coincide with the annual conflagration—including a cozy communal fire burning all day long in their outdoor activity area, crafts and activities for kids and kids-at-heart, free hot apple cider and baked goods donated by the local community, Navajo tacos for purchase, discounts on gear available in their store, and a handful of speakers on topics of local culture and history. Click here for more information.

The monument issue is not yet resolved, and may not be for some time to come, although a recent procedural victory for the plaintiffs and the even-more-recent election of a Native American majority in the San Juan County Commission bode warily well. Nor, for that matter, is the mammoth petroglyph issue fully resolved, and it probably never will be—serious academics stopped paying attention around 2012, yielding the floor to avocational speculators and others. It just wouldn’t be San Juan County if controversy went away altogether.

But when the bonfire erupts in Bluff every winter, spirits are always high, solidarity prevails, and that’s what the midwinter festival is—and always has been—really about.

Yip yip yip!

Bluff’s Winter Solstice celebration will be held on the solstice, December 21, beginning at 7:00 p.m. More information here. For details about happenings at the Bears Ears Education Center, click here.