- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Life in the Cliff Valley, 1300-1450

Our guest author for this post is undergraduate Chris LaRoche. Chris received his Associate’s Degree from Pima Community College’s archaeology program, and also attended the Preservation Archaeology Field School as a Pima student. He is now an anthropology major at the University of Arizona, where he is completing an undergraduate research project supported by the National Science Foundation’s Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) program. — Karen Schollmeyer

(December 11, 2018)—Since the summer of 2016, the Archaeology Southwest/University of Arizona Preservation Archaeology Field School has been conducting excavations at the Gila River Farm site near Cliff, New Mexico. Each field season has seen the collection of thousands of artifacts, including pottery, ground stone, flaked stone, faunal bone, and more. From January to November 2018 I have been at work in Archaeology Southwest’s lab analyzing the Gila River Farm site’s ceramic and ground stone assemblages.

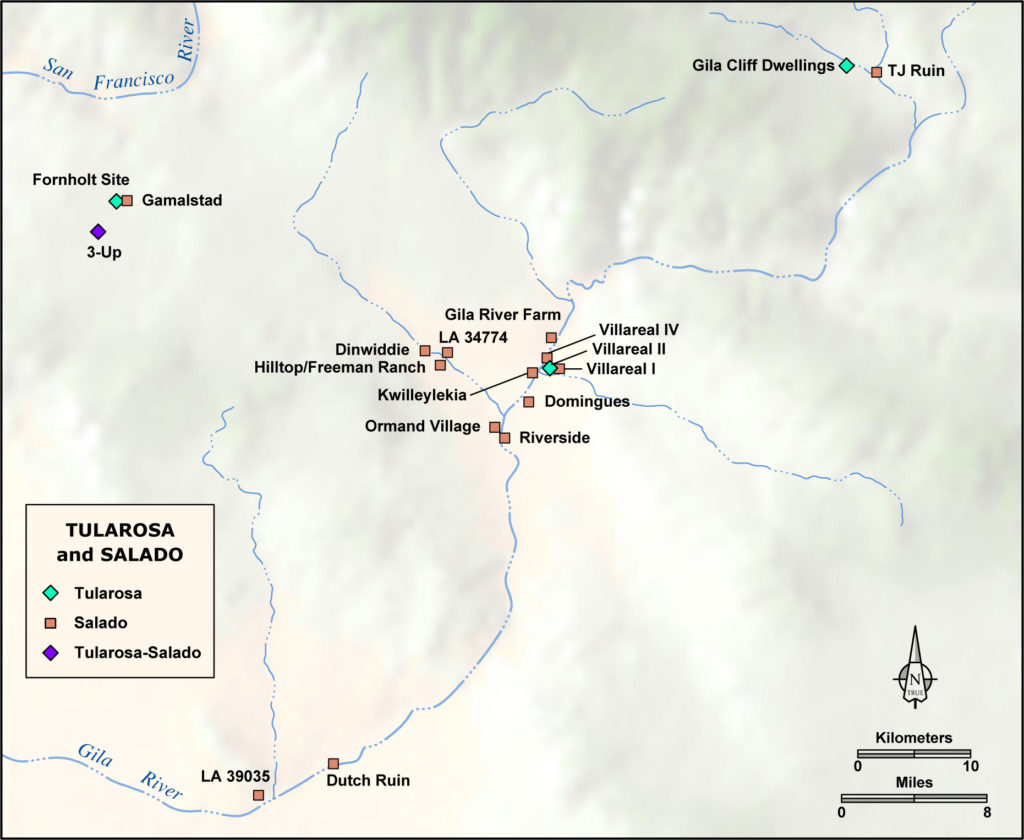

These collections offer the opportunity to examine the cultural affiliations of the inhabitants of this Cliff Phase (AD 1300–1450) village. I’d like to understand how these villagers might have fit into the wider Salado ideological phenomenon of the late prehispanic Southwest, including the population movements that accompanied the Salado expansion. The latter phenomenon has been of great interest to Archaeology Southwest’s ongoing inquiries.

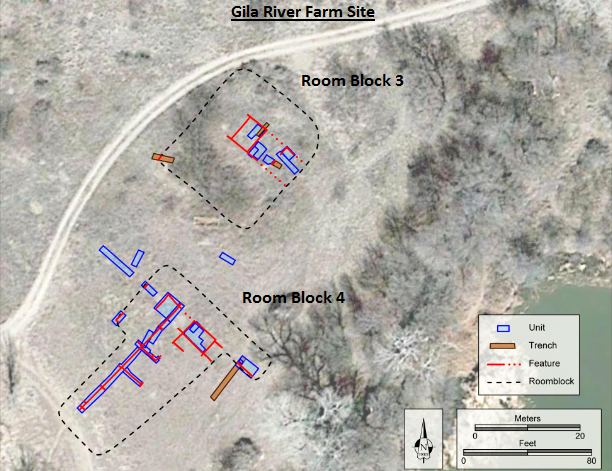

Excavations at Gila River Farm have focused primarily on two roomblocks, Room Block 3 and Room Block 4, and from these the crews have recovered approximately 5,400 ceramic sherds and 230 ground stone artifacts. The ceramic sherd assemblage is largely undecorated plain ware but also contains a variety of decorated wares. These decorated wares are dominated by Roosevelt Red Ware, also known as Salado polychrome, but also include significant quantities of nonlocal types such as El Paso Polychrome and older local Mimbres White Ware. The presence of Mimbres White Ware suggests that the Gila River Farm Site was also the location of a settlement in the earlier Classic Mimbres Period (AD 1000–1130).

The distribution of Salado polychrome is the chief evidence of the Salado phenomenon. This pottery seems to have served an integrative purpose among groups of people in the southern Southwest who had come into contact with Kayenta migrants from the Colorado Plateau. Beyond the decorated wares, the Gila River Farm site also contains the most significant concentration of perforated plate fragments of any site yet investigated in the Cliff Valley or Upper Gila watershed. Perforated plates were a technological innovation Kayenta peoples used in pottery-making. They are considered an indicator of the presence of people of Kayenta ancestry.

Other indicators of cultural connections include the use of grinding stations with bowls inset into the floor of a room. This combination is typically seen in the Mogollon region of New Mexico. Differences in ground stone tool manufacture by local Mogollon inhabitants and Kayenta peoples also exist. Inhabitants of the Colorado Plateau typically made full-groove axes, whereas Mogollon peoples typically made ¾-groove axes (the groove, no matter how far around, was where people hafted the handle to the ax head). Another indicator is the form that manos (used with metates to process maize into meal) from these two regions typically take. On the Colorado Plateau these are often made with finger grooves on the leading or trailing edges of the mano, or both, whereas in the Mogollon area they are made without finger grooves.

With the help of these indicators, I have been able to determine that Room Blocks 3 and 4 contain two related but varied object assemblages. Room Block 3 contains exclusively ¾-groove ax heads and manos without finger grooves, but Room Block 4 contains only a single full-groove ax head and a mix of both mano types. Room Block 3 contains only a single perforated plate fragment and a very high percentage of El Paso Polychrome, whereas Room Block 4 contains over a dozen perforated plate fragments and a much lower percentage of El Paso Polychrome. Within Room Block 3, excavators have identified four inset bowl grinding stations, but there is only a single example in Room Block 4.

Interestingly, Salado polychrome sherds are a majority of the decorated assemblages in both room blocks, though more prevalent in Room Block 4. This includes similar percentages of Salado polychrome subtypes, such as Dinwiddie Polychrome and Cliff White-on-Red, which are exclusive to the Mogollon area under Salado influence. Both roomblocks contain a nearly insignificant amount of Maverick Mountain Series polychrome (three sherds in total), a ware that appears slightly earlier than Salado polychrome and has been linked to the initial Kayenta migrants. Those migrant potters continued to produce pottery in traditional styles but out of local materials collected around their new homes.

This suggests that, during the Cliff Phase, the Gila River Farm site was inhabited by people with two distinct ancestries. They were under the Salado ideological umbrella but not yet fully coalesced into a homogeneous community: people displaying relatively more indicators of Kayenta descent resided in Room Block 4, and residents displaying relatively more Mogollon material culture indicators resided in Room Block 3. The similar distribution of Salado polychrome subtypes suggests that the two roomblocks were contemporary with each other. The lack of significant amounts of Maverick Mountain Polychrome indicates that the residents of Room Block 4 most likely were not themselves immigrants from the north, but rather the descendents of earlier Kayenta migrants who had by this time already adopted a Salado identity while still retaining certain other attributes of Kayenta material culture.

When looking at the Salado component of the Gila River Farm site as a segment of the regional Cliff Phase social landscape, some parallels emerge. Two other Upper Gila sites also show stronger indicators of Kayenta heritage in certain parts of the village: Dinwiddie (also in the Cliff Valley) and 3-Up (located near Mule Creek).

Dinwiddie has three roomblocks, of which one, Room Block 3, features a much lower percentage of El Paso Polychrome and a higher percentage of Salado polychrome compared to other roomblocks in the village, as well a significantly higher percentage of perforated plates. Only minor amounts of Maverick Mountain Series pottery occur throughout the Dinwiddie site.

At the 3-Up site, Room Block B shows strong indicators of Kayenta heritage. Spatially separated from Room Block A by about 150 meters (~500 feet), it contains a high incidence of Maverick Mountain Series polychrome (over 25 percent of the decorated assemblage). This is more than 12 times that of the Dinwiddie site and more than 50 times that of the Gila River Farm site. Room Block B of the 3-Up site may represent the only known Kayenta enclave in the region settled by a group of Kayenta migrants originating from their ancestral lands. It probably predates the Dinwiddie and Gila River Farm sites.

A fourth major Cliff Phase community in this area is Ormand Village, which appears to be roughly contemporary with the other three sites discussed here based on its ceramic assemblage. Its assemblage contains very little evidence of Kayenta heritage expressed through artifacts, and represents a relatively homogeneous Cliff phase Salado community. This suggests that, even without the presence of Kayenta migrants or their descendants, the nature of the Salado ideology was sufficient to bring about its adoption by local Mogollon villages whose inhabitants did not have strong ancestral ties to the Kayenta area.

Through the combination of existing data from the area and new data being collected from the Gila River Farm site, a picture of life in the Cliff Valley in the 1300s and 1400s is emerging.

Funding for Chris’s research—and all our field school projects—was provided by the National Science Foundation (REU 1359458 and 1560465), University of Arizona Foundation, and Archaeology Southwest members. Thank you!

Explore the News

Related to This

-

Post Women’s Work