- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- (Yet) Another Southwest: Incipient Preservation Ar...

(February 15, 2019)—What is it that keeps push-pulling me toward the equator and setting sun? My earliest engagements with archaeology included a fifth-grade fieldtrip from my Denver hometown through the Four Corners, where all-new exposures to cliff dwellings, families of Navajo shepherds, and enchiladas (among other cosmic revelations) blew my inner-city-kid mind. Thus kindled by green chile and frybread, the fire of my imagination burned low but steady, with occasional flare-ups fueled by Willa Cather, Tony Hillerman, and Arizona Highways.

The ink wasn’t dry on my upstate New York college diploma before I had relocated, in July of 1983, to Tucson, a move that inspired an oath to never again wear long pants or eat a greasy grinder (a pledge that lasted at least five years and still prevails, mostly). It took a 2005 job offer at Simon Fraser University to drag me away from Arizona and to Canada (my maternal homeland!). There, greeted by the boundless opportunities of vast northern expanses populated by magnificent archaeological records and eager Indigenous community project partners, what did I do? I turned, on a dime, southwesterly, focusing a decade of research and outreach on Stó:lō and Tla’amin First Nations Territories, both close to Vancouver, in southwest reaches of Canada’s southwest province, British Columbia…

Most recently, in pursuit of another boyish dream—to explore the wilds of Ethiopia (think of the proud cattle herders of the Rift Valley’s Turkana Basin, the original home of coffee and, so far as we know, of humankind itself)—where did I land? In lovely, hazy Jinka, Ethiopia’s southwestern-most city and home of Jinka University.

There, for most of the first half of January, my beloved Jami Macarty and I served as visiting faculty members, hosted by Dr. Alemseged Beldados, an accomplished archaeobotanist I had befriended while he was visiting Vancouver in 2017. “Dr. Alem,” as he is known by his fine colleagues, serves as the vice-president academic, Jinka U’s chief academic officer. In this capacity Alem is a premier example of an archaeologist deploying at least four of what I consider to be among the best and most broadly useful aspects of our disciplinary “culture”—sociability, interdisciplinarity, rigor, and humility.

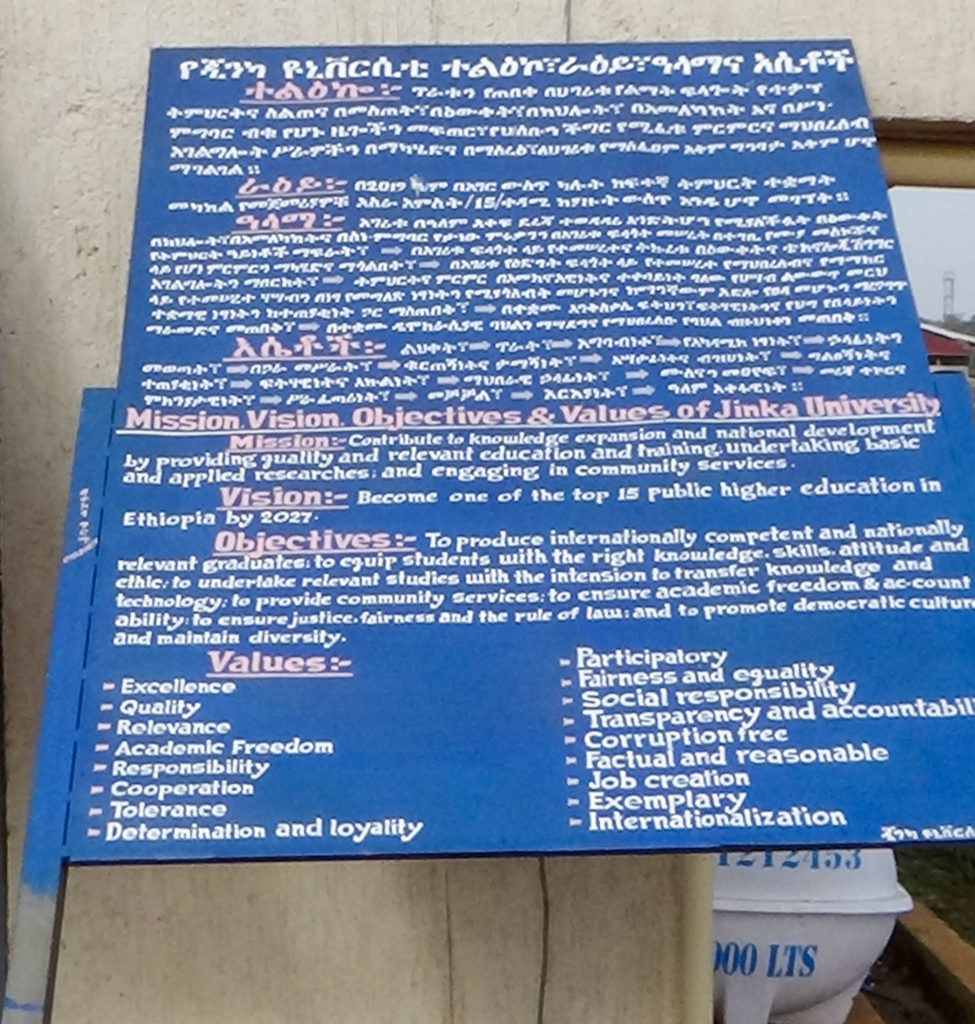

Founded in 2016, Jinka University is one of a dozen new universities Ethiopia has launched in the last decade to meet the surging demand for highly qualified personnel needed to navigate the challenging and fast-paced path from pre- to post-industrial society. All courses in all Ethiopian national universities are taught in English, the second or third (or fourth!) language for all but a small fraction of students and instructors. Ethiopia’s education ministry assigns both students and faculty to universities, a scheme to balance mandates to concentrate and match faculty expertise, regional economic potential, and student career interests with the need to integrate Ethiopia’s astonishingly diverse and regionalized concentrations of languages, cultures, and ethnicities. The 2007 census identified 48 different Ethiopian (and neighboring) ethnic groups within the greater Jinka region, alone!

In keeping with overarching questions about how to harness and focus the power of multiplicity, our primary mission at Jinka was to launch OVJ—Omo Valley Journal of Cultural and Biophysical Diversity, a peer-reviewed journal, professionally managed to examine, celebrate, and connect South Omo Valley peoples and places with the world. The assignment was tailored to contribute to the university’s strategic plan and to take advantage of Jami’s experience as editor of the online poetry journal, The Maynard and my work in transforming the SFU Archaeology Press into an open access journal.

Jami and I also delivered a suite of lectures and faculty development workshops. Faculty, students, and staff graciously diverted from their classes and other responsibilities to crowd into various venues to participate in dialogues about participatory teaching, lifelong learning, the art of balancing faculty privileges with social responsibilities, poetry, and archaeology.

There are, of course and always, the twinned uncertainties and promises of alchemy in the convergence of hearts and minds previously separated by geographical, cultural, linguistic, and institutional boundaries. The golden moments that precipitated from our encounters at Jinka U shined through the smog from the region’s charcoal fires and field burning. Enthusiastic participation in the dialogues we initiated seemed in stark contrast to the often hyperspecialized and intellectualized discourse prevalent in North American universities. The warm spirit of adventure, collaboration, and gratitude that pervaded our brief visit left us convinced that we had received at least as much inspiration as we left behind.

The dialogues I facilitated centered, naturally enough, on preservation archaeology. Ethiopia, and the South Omo Valley in particular, are world-renowned bastions of locally treasured and conserved places, objects, and traditions—a veritable and venerable proving ground for heritage stewardship, not to mention ethnoarchaeology and community-based inquiry. Ethiopia provides stewardship for nine World Heritage Sites, the most of any African country. Jinka University’s mandate includes a special emphasis on archaeology and heritage. Five of the university’s roughly 100 faculty and staff are archaeologists, a high percentage by any standard.

This concentration of expertise is attributable in part to the South Omo region’s numerous, highly significant archaeological and paleo-anthropological sites, including the Lower Valley of the Omo UNESCO World Heritage Site. Outstanding universal value (OUV) to humankind is the criteria of world heritage site inscription, and OUV for the Lower Valley of the Omo centers on finds of the fossilized skeletal remains of australopithecines (Homo gracilis) in stratigraphic contexts with the remains of numerous other species, stone tools, and possible encampments.

Governments and tour operators include references to early hominid sites in their marketing materials, and Ethiopia is increasingly branded as the “Land of Origins.” But almost nothing is being done to ensure that the local people being obliged to tolerate visitors are receiving benefits in proportion to the degree to which they must adjust their lives, livestock distributions, economies, travel patterns, and attitudes to accommodate tour groups, researchers, and other intrusions. The massive Gibe III Dam, upstream on the Omo River, is adding complexity and frustration for local residents, especially the Indigenous peoples. Studied, balanced, and locally contextualized heritage interpretation, as well as fair and transparent benefit and information sharing, are essential to fulfill the promise of heritage tourism in the South Omo and elsewhere.

Our stints as visiting faculty members in Ethiopia proved that the decades of famine and strife the country is most widely known for are no match for good faith and person-to-person collaborations, not to mention boyish imaginings and the irresistible gravitational pull, at least on me, to all southwests.

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.