- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- The Women’s Park

Today and tomorrow we feature guest author R. E. Burrillo’s essay on “the mothers of Mesa Verde National Park” in honor of Women’s History Month.

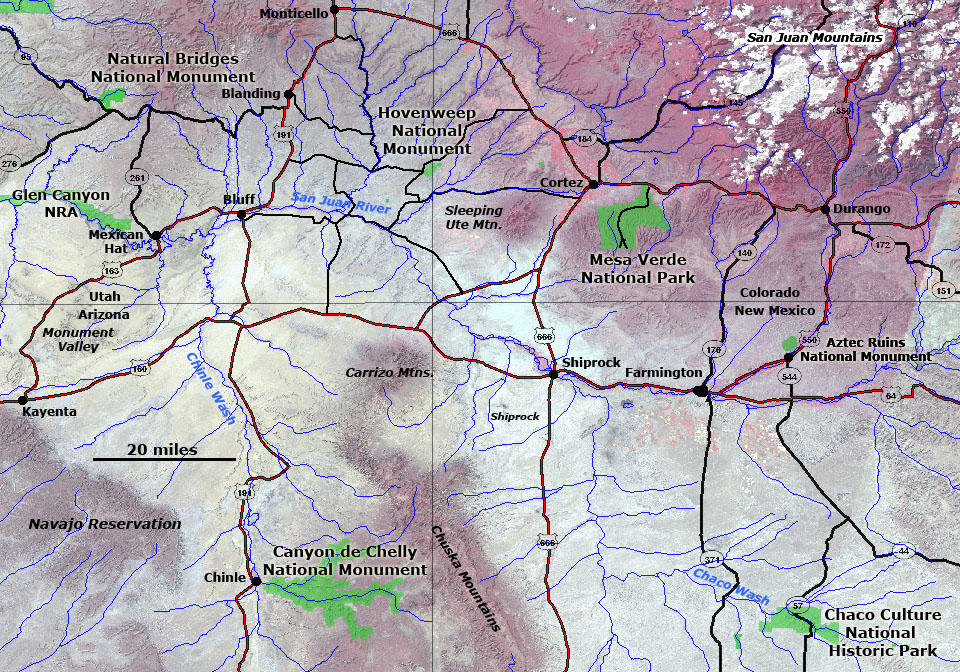

(March 29, 2019)—Last March, in recognition of Women’s History Month, archaeology professor Ruth Van Dyke took to Facebook to ask folks to name their favorite unsung women in archaeology. I think I went with Anna O. Shepard, the foremother of ceramic analysis, at the time. As a specialist in the archaeology and cultures of Bears Ears, the westernmost part of the Mesa Verde region, I could have named two others: Virginia Donaghe McClurg and Lucy Peabody—the mothers of Mesa Verde National Park. For this year’s Women’s History Month, I decided to write about them.

What Is Mesa Verde National Park? Who Lived There in the Distant Past?

Mesa Verde National Park encompasses most of the major drainage systems of a high plateau (the Mesa itself) dividing Mancos and Montezuma Counties in southwestern Colorado, adjacent to the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation (where there is a tribal park that is also well worth visiting). The landform is named for being among the richest and most verdant environments in Colorado, owing to the amount of rainfall it receives compared with the surrounding region, and its name—literally “Green Tableland”—derives from its luxuriant transitional and upper Sonoran vegetation communities. Ancient Pueblo people knew a good place to make a life when they saw it.

The earliest inhabitants of the Mesa were farmers who were there part-time to take advantage of the rich late-summer rain and the porous, snowmelt-retaining soils on the mesa top to grow their crops. Full-time residence on Mesa Verde probably didn’t occur until about AD 500 or so, when people throughout the region began moving uphill to follow the elevational dry-land farming belt and escape low-altitude droughts (the same thing happened roughly contemporaneously in the Durango and Bears Ears areas). Crow Canyon Archaeological Center in nearby Cortez has an excellent replica pithouse based on examples known from Mesa Verde from this era, and in the park itself you may visit several partially excavated pithouses from this era and a little later in time.

Most people don’t go to Mesa Verde or the nearby tribal park to see farmers’ pithouses, though. They go to see what Stephen Lekson has called the “last-ditch effort” to reside there. Sometime during the late 1190s, after living primarily atop the mesa growing crops for about 600 years, people began moving into structures built into natural openings in the walls of the cliffs.

Explanations vary as to why this happened. In general, we know that extensive occupation and land-use in ecologically constrained niches stretches the carrying capacity of the land pretty thin. When regional climate and the Chaco social system each took a nosedive in the early 1100s, communities in Mesa Verde undoubtedly felt a ton of pressure from both.

In any event, people throughout the Ancestral Pueblo world shifted their settlement strategy from a focus on open settings with good farmland to a focus on “defensible” canyon and cliff locations near reliable water sources. For all the might and majesty of superstructures such as Cliff Palace, most of these were inhabited for less than a century (which still sounds like a long time for a single contiguous building to be inhabited, but compare that with extant Pueblo villages at places like Taos and Hopi—both of which have housed residents for 1,000 years or more).

Euro-Americans in an Ancient Landscape

People had probably been poking around the iconic cliff structures of Mesa Verde since Euro-Americans began arriving in the region, but recreational visitation of the place didn’t ramp up until after 1888, when local rancher Richard Wetherill started telling the world about what he and his brothers had “discovered” there.

At the time, there were no laws in place to protect antiquities, which were regarded the same as any other wildland resource—there for the taking. If you wanted wood to build a house, you chopped some trees down; if you wanted ancient pots to adorn the fireplace in that house, you dug some up. Simple.

Although the struggle to protect ancestral Indigenous sites and materials in the United States is a massive subject in its own right, it’s worth noting that the late 1800s were also the time when gentleman hunter-scholars were setting the American conservation movement into motion. Starting with Teddy Roosevelt’s Boone and Crockett Club in 1887, lobbying on behalf of saving—or at least more intelligently managing—the flora and fauna of America’s forests, plains, and waterways exploded in the 1890s, culminating in the Forestry Reserve Act (1891) and numerous other pieces of legislation thereafter. That helped take care of the “trees” bit of people’s unfettered exploitation, but not the more egregiously immoral looting and grave-robbing.

This shift in political attitudes to one of restrained and scientifically informed management accompanied what scholars often call the “closing of the West” in about 1890, although, as postmodern critics such as Patricia Limerick have pointed out, this concept only meant closure of limitless range acquisition by wealthy white men. Women, Hispanics, freed slaves, and Native Americans who struggled daily to maintain agency and identity in the West didn’t really count.

Nor had the body of American archaeology itself yet been imbued with more modern decency. Consider the following letter by Dr. Arthur Frothingham, founder of The American Journal of Archaeology, written in 1888 after a reader dared to ask why the journal never actually dealt with the archaeology of America:

The archaeology of America…is busied with the life and work of a race or races of men in an inchoate, rudimentary, and unformed condition, who never raised themselves, even at their highest point, as in Mexico and Peru, above a low stage of civilization, and never showed the capacity of steadily progressive development. Within the limits of the United States the native races attained to no high faculty of performance or expression in any field. They had no intellectual life. They have left no remains indicating a probability that, had they been left in undisturbed possession of the continent, they would have succeeded in advancing their condition out of the prehistoric state. The evidence afforded by their works of every kind—their architecture, their sculpture, their writing [sic], their minor arts, their traditions—seem all against the supposition that they had latent energy sufficient for progress to civilization.

That a distinguished professor of history could publish such a thing is shocking today, but telling of the era in which it happened. (I also quoted Frothingham’s letter in a recent article published in The Archaeological Record.)

Meanwhile, and in contrast, the aforementioned Wetherills deserve credit for their advanced thinking in this regard: whereas most American history scholars were studying Egyptian pyramids and ignoring American archaeology as the garbage of savages, prominent Native American figures such as Wolfkiller and Mancos Jim were friendly associates of the Wetherills. In fact, patriarch B. K. Wetherill was among the first people to urge protection of Mesa Verde as a National Park in a letter he wrote to the Smithsonian.

Thus, while the next decade saw admittedly well-meaning men such as Roosevelt, Burroughs, Grinnell, and Muir lobbying to save America’s wilderness for the enjoyment of future hunters and ranchers, Native Americans and American women still watched from the sidelines, and in some places a sense of camaraderie began to take hold.

Enter Virginia Donaghe

Out of that sociocultural stew stepped Virginia Donaghe, a correspondent for the New York Daily Graphic who resided in Colorado Springs. In the mid-1880s she was dispatched to write a story about the ancient structures of southwestern Colorado and, like many of us, she became instantly and hopelessly addicted. She wanted to explore them, study them, draw them, photograph them, and then explore them some more. Unlike almost every other visitor to Mesa Verde at the time, however, she didn’t want to dig in them for ancient loot to carry away. She wanted to save them.

Virginia published sketches and gave numerous public talks about the cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde for the rest of the 1880s. She spoke at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, the same event where Richard Wetherill met the Hyde brothers and began planning his expeditions into the Bears Ears area, and where Roosevelt’s Boone and Crockett Club drew the attention and support it needed to pass subsequent legislation like the National Wildlife Refuge System Act of 1903. Following her final public lecture in 1894, a petition—initiated by colleague Mary Caroline Bancroft—was circulated calling for protection of Mesa Verde as a national park. The petition died in Congress, but Virginia (now with the married name McClurg) was invigorated.

Colorado was among the first states to give women the vote, also in the momentous year of 1893, and although mainstream history often glosses over this, the suffragist battle was a nasty one. Women in Colorado were eager for any unifying common cause toward which to direct the wave of vitality associated with that victory. With the wondrous material history of the still-disenfranchised Native Americans of the Southwest, Virginia provided one.

By 1897, she had amassed the public support of over 250,000 women through the Colorado Federation of Women’s Clubs, and had persuaded this federation to appoint a standing committee to “investigate and promote the cause of the Colorado cliff dwellings,” which became autonomous as the Durango-based Colorado Cliff Dwellings Association in 1900. Its motto was Dux Femina Facti, which loosely translates as “feminine leadership has accomplished this.” Among their first tasks was to secure a lease from the Ute Mountain or “Weeminuche” Utes, whose land included Mesa Verde, a task which took Virginia on a series of lengthy field excursions just to find the right signatories. She eventually found—and found favor with—Chiefs Ignacio and Acawitz, the former of which refused her at least once before acquiescing. The subsequent 1901 treaty gave the Colorado Cliff Dwellings Association water rights, permission to build and improve roads, and so on.

Later that same year, the Association shrewdly invited Dr. Jesse Walter Fewkes of the Smithsonian’s Bureau of American Ethnology to come and tour the dwellings while he was in Denver attending a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. He accepted, and would later become the chief pioneer (after Wetherill) of archaeological investigations at Mesa Verde.

Side note: In his 1916 paper in the Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution, Fewkes wrote: “Of man when he first entered the Southwest, we know little save that his physical features show that he was an Indian.” Setting aside his antiquated use of “man” to refer to humankind and “Indian” to refer to Native Americans, Fewkes’s assertion stands as an early and strong assertion that the people Frothingham and his ilk dismissed as savages were the same ones who built architectural wonders that rivaled those of ancient Rome. The idea that Native Americans are too backward a people to have ever constructed Cliff Palace, Tenochtitlan, or Chichen Itza is an especially insidious prejudice that endures to this day in guises like the insufferable television program Ancient Aliens.

Enter Lucy Peabody and Edgar Lee Hewett

Virginia McClurg became a celebrated public speaker over the next half-decade, and was soon joined at the helm of the Mesa Verde effort by Lucy Peabody. Although holding a lower rank than McClurg in the Association, Peabody undoubtedly knew more about America’s ancient history, having served as a secretarial assistant in the Bureau of American Ethnology before marrying the executive officer of the United States Geological Survey. When she and her husband moved to Denver after his retirement, Lucy became very influential in Colorado politics, including successfully pushing for child-labor laws and the recognition of Lincoln’s birthday as a state holiday. Lucy’s working knowledge of politics, combined with what she knew about Native Americans and their history from her time at the Bureau, made her a natural in the fight to protect Mesa Verde—as well as a threat. Tensions between Virginia and Lucy began simmering almost immediately.

By 1905, a total of five bills to create Mesa Verde National Park had all met a humiliating end in Congress. Stung by these repeated defeats, Virginia abruptly and wholeheartedly reversed her position. Concluding that Washington was filled with corrupt monsters, she refocused her energies toward a more localized goal. Mesa Verde could only work as a state park, owned by Colorado and managed by her group, because they were the only people who really seemed to care. The compulsion of an increasing number of federal officials to preserve wild animals so that their own grandchildren could shoot them did not, it seemed, extend to preserving irreplaceable ancient wonders so that those same grandchildren could visit them. Or so went Virginia’s frustrated thinking.

Lucy Peabody, on the other hand, was undeterred in her conviction that federal protection was the way to go—especially once she began corresponding with Edgar Lee Hewett, one of the first (and most diligent) of a new era of institutional archaeologists in the United States. Hewett despised Richard Wetherill; although Wetherill had learned a lot about science from rubbing elbows with people like Gustaf Nordenskiöld and T. Mitchell Prudden, he didn’t have a degree to prove it, and Hewett saw him as little more than a jumped-up looter. Hewett was eager for a way to get Wetherill removed from his current situation as antiquities excavator and trader in Chaco Canyon. And yet there weren’t any federal archaeological protection laws for Wetherill to be guilty of breaking.

The second part of Burrillo’s essay is here.

To read more about McClure, Peabody,Wetherill, Nordenskiöld, and Hewett, check out Bill Doelle’s articles in Archaeology Southwest Magazine 26-1 (free PDF download).