- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Fighting the Bears Ears Downsizing (with an Agèd ...

(June 28, 2019)—On June 8, 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt signed the Antiquities Act into law.

And yet, 113 years later, in the year 2019, at about the same time, there were no headlines announcing that President Roosevelt had risen from his grave to make an appearance in Monticello, Utah, where the Bears Ears Monument Advisory Committee met earlier this month.

I wish he had.

In my mind’s eye, I can see him storming in, making at least three points—and perhaps many more. I can hear him directing some pointed questions to the committee members and federal employees leading the meeting.

“Now, I grant you, the process of protecting public lands has indeed grown complicated since my time in office,” he would concede, eyeing each official in turn. “But on the heels of an 85-percent reduction in protected land area, how do you justify rushing the all-important process of preparing the management plan for what is left?”

(Some intakes of breath, some strangled coughs. He would pace a bit in a lengthening silence before rounding on them again.)

“And though I have checked, it does not seem as though any of you had raised your voices in support of the establishment of Bears National Monument in the first place. That tells me you bring a narrow set of views to the table. Why should our citizens trust that you will offer thoughtful and balanced words to ‘guide the management’ of the sacred cultural and natural resources of this place?”

Moreover, Mr. Roosevelt surely would have called out the current president’s disrespectful treatment of the five sovereign tribal nations who led the effort to establish Bears Ears National Monument. In President Obama’s proclamation of 1.35 million acres on December 28, 2016, he created a Bears Ears Tribal Commission “to ensure that management decisions affecting the monument reflect tribal expertise and traditional and historical knowledge.” Less than a year later, President Trump cut 85 percent of the Bears Ears land area, and he cut the role of the Tribal Commission even further—to a mere 10 percent of the original area.

Finally, Mr. Roosevelt absolutely would have reeled off numerous facts regarding diminished protections for the remarkable historical and archaeological resources of the Greater Bears Ears region.

Although I rue Mr. Roosevelt’s unlikely return, as a committed Preservation Archaeologist, I will nevertheless gather together a package of facts to support his third area of concern. It’s always good to be prepared. And, to ensure that Mr. Roosevelt (or other, more corporeal officials) are well prepared, some of what follows may get a bit technical.

We do not know the exact number of sites that the Obama proclamation would have protected, but the 30 archaeologists who participated in an expert-guided synthesis session in Bluff in July 2017 estimated that about 10 percent of the area had been surveyed and that roughly 100,000 archaeological sites were probably, statistically, present.

Accepting that consensus total, I reasoned that the number of known sites in the area excluded from the monument and the number remaining in the shrunken units should provide a simple estimate of how many sites are no longer protected by monument status.

I worked directly with staff members at the Utah Division of State History. They maintain the official archaeological site records for the entire state. I contracted with them to pull as precise a list of archaeological sites from their database as possible. That database is a geographic information system, or GIS, that enables them to use the shapes of the Obama and Trump national monument boundaries to identify all sites that fall within or intersect the boundaries of those monuments. Here are those numbers:

| National Monument | Known Sites | Percentage |

| Obama 2016 | 7,693 | 100% |

| Trump 2017 | 2,043 | 27% |

| Sites excluded by Trump | 5,650 | 73% |

If we use the above table and assume that the 100,000 sites of the entire Obama monument are distributed roughly like the above percentages of known sites, then the Trump monument protects only 27,000 sites, and 73,000 sites are excluded from the higher levels of protection a national monument provides.

Seventy-three thousand is, unarguably, a very large number. Think about that: some 73,000 sites left unprotected. (Using the best-available data, Mr. Roosevelt now has a strong talking point to lead with, wouldn’t you agree?)

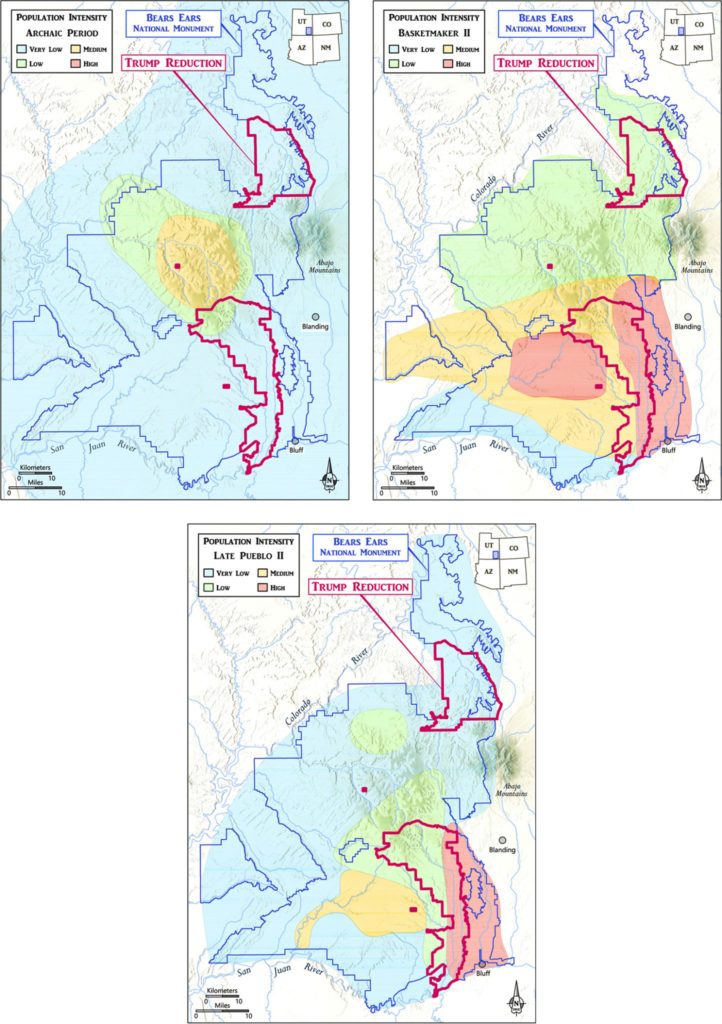

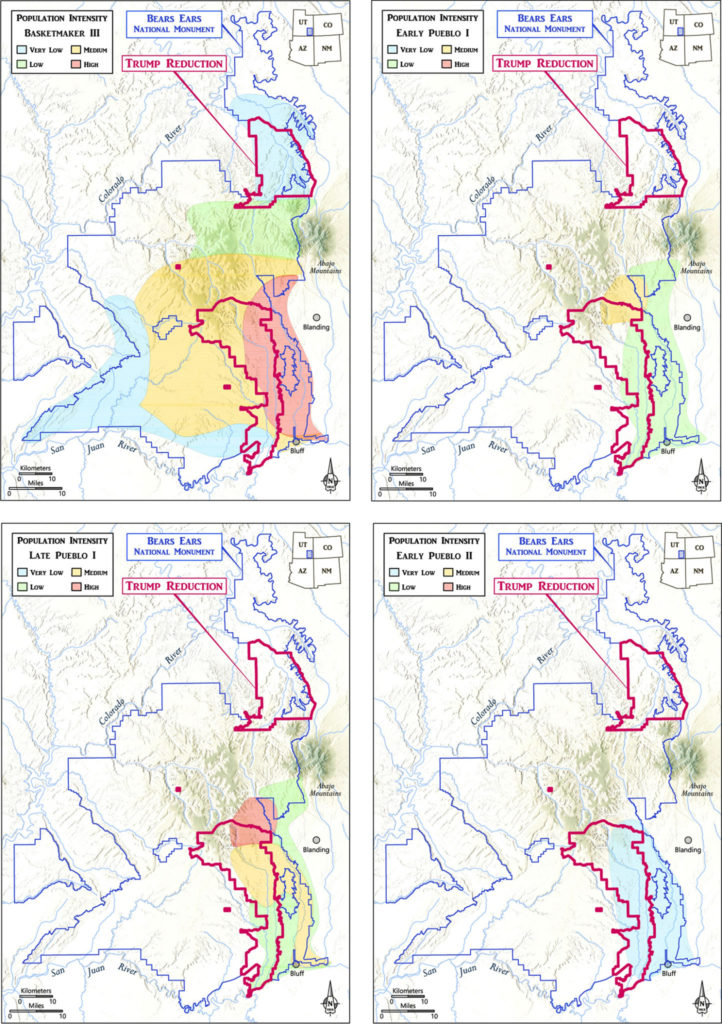

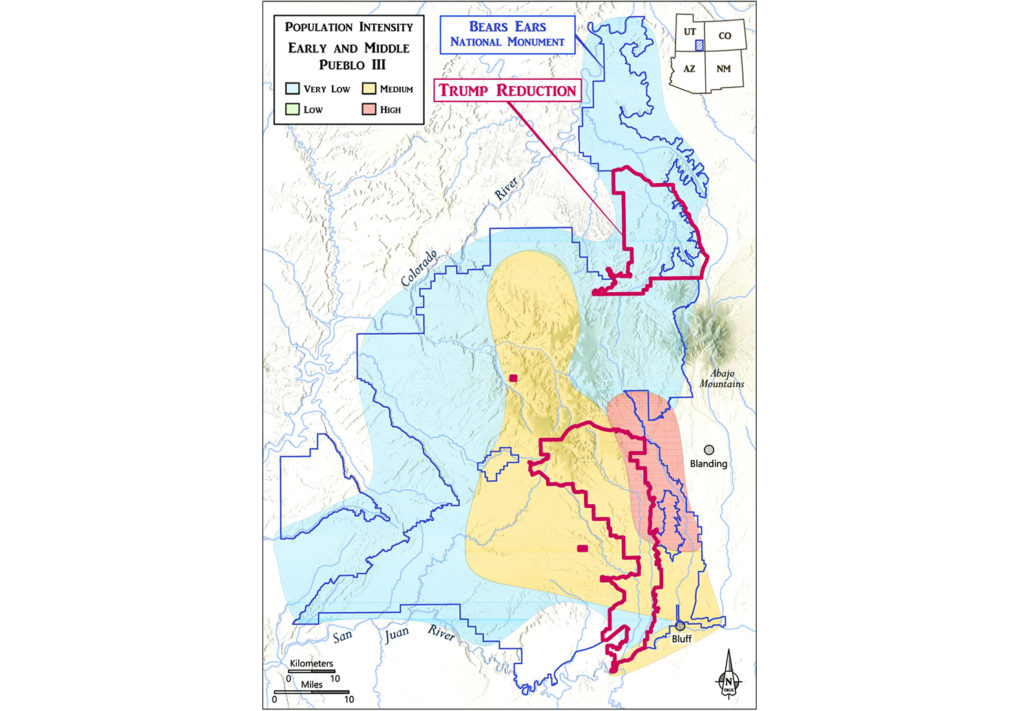

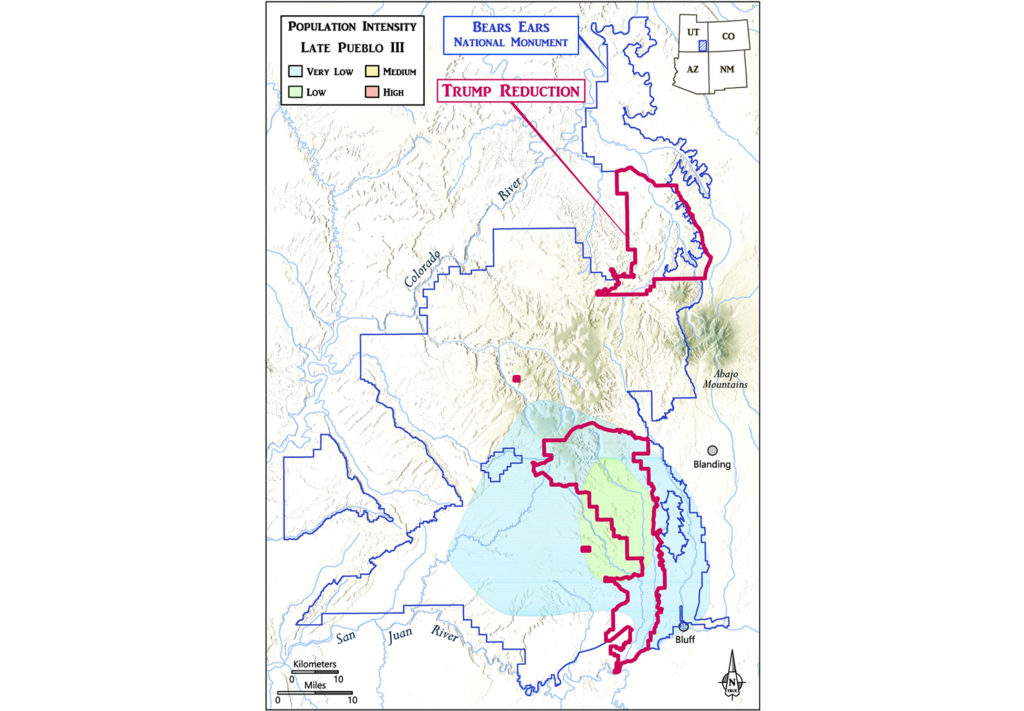

But numbers are dry, and some people just don’t relate to them. So, let’s move on to some maps and images. This is where the deliberations of the 30 archaeological experts in July 2017 really pay off. Working as a group focused on one map at a time, the experts created visuals that display their consensus of how population intensity varied over the course of 8,000 years across the Greater Bears Ears landscape.

These maps illustrate dramatic changes in land use and population intensity over time. Now, I don’t know what individual or group drew the lines for the downsized Trump monument, but it is clear that they did not attempt to encompass the landscape-scale diversity of the Obama monument.

For the nine maps displayed here, I categorize three as “Big Misses,” four as “Partial Samples,” one as a “Poor Sample,” and one as a “Lucky Hit.”

Big Misses

For the three maps above, take a look at where the most intensely populated parts of the landscape were in those time periods. You can tell from the topography that people were using different parts of the landscape more intensively at different times—for example, when they were reliant on hunting and foraging (upper left) and when they were more reliant on farming (upper right and bottom). How do the downsized monument boundaries compare to past use of the landscape?

Partial Samples

Comparing the downsized boundaries here to what experts know about what is on the ground shows that although the boundaries do capture some of the diversity of people’s lives on this landscape through time, those boundaries do not seem to have truly attempted to account for that. To me, the redrawn boundaries still seem to cut off in the middle of nowhere.

Poor Sample

A head-scratcher.

Lucky Hit

In this time period, people were leaving the area, and this shows where remaining populations were living. The reduced boundary does reflect that—but was it intentional?

I present each of the maps in temporal order with the above labels. Because the time periods in the “Big Miss” category underscore the inadequacy of the downsized monument in representing the full range and scale of past human use of this area, I’ll give them some expanded commentary.

- Archaic—though there is a light scattering of Archaic, or pre-farming, use of the entire Obama monument, the highest density is concentrated in the high-elevation area, which was fully excluded from the downsized monument.

- Basketmaker II—there was a great florescence of early farming activity in the southern half of the Obama monument, with the highest intensity along the eastern edge and across the pinyon-juniper expanse of Cedar Mesa. The Trump monument catches a portion of the former and none of the latter. And the dramatic petroglyphs, pictographs, and cliff dwellings of Grand Gulch are likewise ignored. Put bluntly, Bears Ears without Grand Gulch and Cedar Mesa? Makes no sense.

- Late Pueblo II—there are some similarities between Basketmaker II and Late Pueblo II land-use patterns, so the Trump monument is again a “Big Miss” during this time interval. In addition, during Late Pueblo II and into Early and Middle Pueblo III, there was a growing presence in the Beef Basin area in the north-central portion of the Obama monument. This area is completely excluded by the Trump monument.

Perhaps the “Lucky Hit” merits a brief explanation. In Late Pueblo III times, population was in the final stages of leaving the Bears Ears area. The final remnants of population were concentrated in a fairly limited area, and the southern unit of the Trump monument seems to have nearly centered on the reduced zone. Perhaps that was a factor considered by the unknown boundary-drawers, but I doubt that Mr. Roosevelt could be convinced that was the case.

The value of a landscape scale is that it is the best tool to capture the diverse human stories represented in the archaeological record of an area. These maps and images make it clear that the Trump-downsized monument fails to encompass very important aspects of the cultural and temporal diversity of the larger, landscape-scale monument established by Obama’s proclamation.

It is very important that concerned citizens be aware of the fact that the Trump administration is moving full-bore to lock the downsized Bears Ears into place. The administration has pushed the BLM and Forest Service to create a Draft Monument Management Plan (MMP) in less than a year. It is deficient (read our comments here [opens as a PDF]), and in late summer or soon thereafter, we expect a still-deficient Final MMP. Lawsuits will be filed.

Lawsuits are already inching forward in response to Trump’s 2017 proclamation. The core legal issue related to President Trump’s proclamation of December 4, 2017, is whether Congress ceded the power to a president to revoke or substantially reduce the size of an existing national monument. It is clear that the Antiquities Act of 1906 gives a president the power to declare a national monument in order to preserve and protect “historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest.” The issue of presidential authority to diminish or revoke a national monument is currently in litigation and will be resolved by the federal court system.

In the meantime, threats to this remarkable place accumulate.

Which brings me back to the Antiquities Act itself, legislation that derived from grassroots actions by concerned local communities and ultimately came to the national stage. This same spirit and resolve has been galvanizing grassroots work in Bears Ears country.

- The last election brought a majority of tribal voices to the San Juan County Commission, which in turn led the commission to overturn its legal opposition to the monument.

- The nonprofit Utah Diné Bikéyah advocates for sustainable economic development planning that builds on the strengths of San Juan County and takes action to overcome systemic barriers.

- The Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition is also engaged in long-term planning at the scale of their original 1.9 million-acre national monument proposal, an idea that draws renewed energy and support from the ANTIQUITIES Act of 2019, a bill cosponsored by New Mexico Senator Tom Udall and New Mexico Representative Deb Haaland.

- Bluff-based Friends of Cedar Mesa is doing incredible work through their Bears Ears Education Center, through which they and community volunteers undertake service projects that help protect important places of the past.

All of this work has national implications and is worthy of broad national support.

The mettle of Mr. Roosevelt and countless others who advocate and fight for public lands every day is why we will prevail. I cannot think otherwise. I will not. Are you with us?

2 thoughts on “Fighting the Bears Ears Downsizing (with an Agèd Friend)”

Comments are closed.

Restore Bears Ears NM to its original size. Show respect for our Native American brothers. It is the least we can do.