- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Life of the Gila: Public Lands of the Gila Watersh...

(March 30, 2020)—This series has explored what landscape-scale archaeology, accumulated over some 130 years, illustrates about how past residents of the greater Gila Watershed thought about themselves and their neighbors. We focused on the big picture—time periods when the archaeological record suggests that people had group identities, ways of thinking of themselves, that extended well beyond the local community or near neighbors.

We emphasized this large scale by using the term “worlds” to refer to these periods of expansive identities. In order to sketch the stories of those worlds, archaeologists document traces that come from on and within the land. Thus far, we haven’t paid attention to land ownership. What lands have yielded this information about the past, and where is such information still preserved?

These are important questions. Land in the United States has owners—of many different kinds. We readily grasp the concept of private land—where someone paid (or is paying) for land and holds a deed that gives them rights to control how that land is used and who may enter it. In the western United States, public land is abundant, and that is the complicated story I want to explore here.

Public Lands

But first, what do we mean by the term “public lands?” John Leshy, one of America’s premier authorities on this topic, notes that there is no precise legal definition of the term “public lands.” His solution: “I use it to mean those lands owned by the U.S. that are generally open to the public and managed for broad public purposes. They are overseen by four federal agencies—the National Park Service, the U.S. Forest Service, the Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Bureau of Land Management.”

This is not a new issue. (Allow me a brief historical digression.) In fact, public lands played a critical role in the founding of the nation in the 1700s. In Debunking Creation Myths about America’s Public Lands, Leshy describes a major sticking point that emerged in 1776, soon after the signing of the Declaration of Independence. To create a structure for governance for the newly independent colonies, leaders drafted the Articles of Confederation and presented them to the former colonies for signature. Because roughly half the colonies had lands that extended westward to the Appalachian Mountains and beyond, and the others were bounded on their western margins, the landlocked colonies balked at signing the Articles. This impasse was resolved when the “unbounded” colonies agreed to deed their western lands to the federal government as public lands.

Just a few years later, public lands were clearly on the minds of the men drafting the U.S. Constitution. They gave control over the public lands to Congress, in Article IV, Section 3, the so-called “Property Clause.” It reads, simply, “The Congress shall have Power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States.”

These are the administrative “origins” of the U.S. public lands. But it is critical to recognize that these public lands were carved out of the traditional lands of Native Americans. True, big expansions of the United States such as the Louisiana Purchase and land cessions and purchases from Mexico did involve transfers from other colonial powers. But those lands were originally wrested from Native peoples. Respectful acknowledgment of the tribal origins of those lands is an essential starting point.

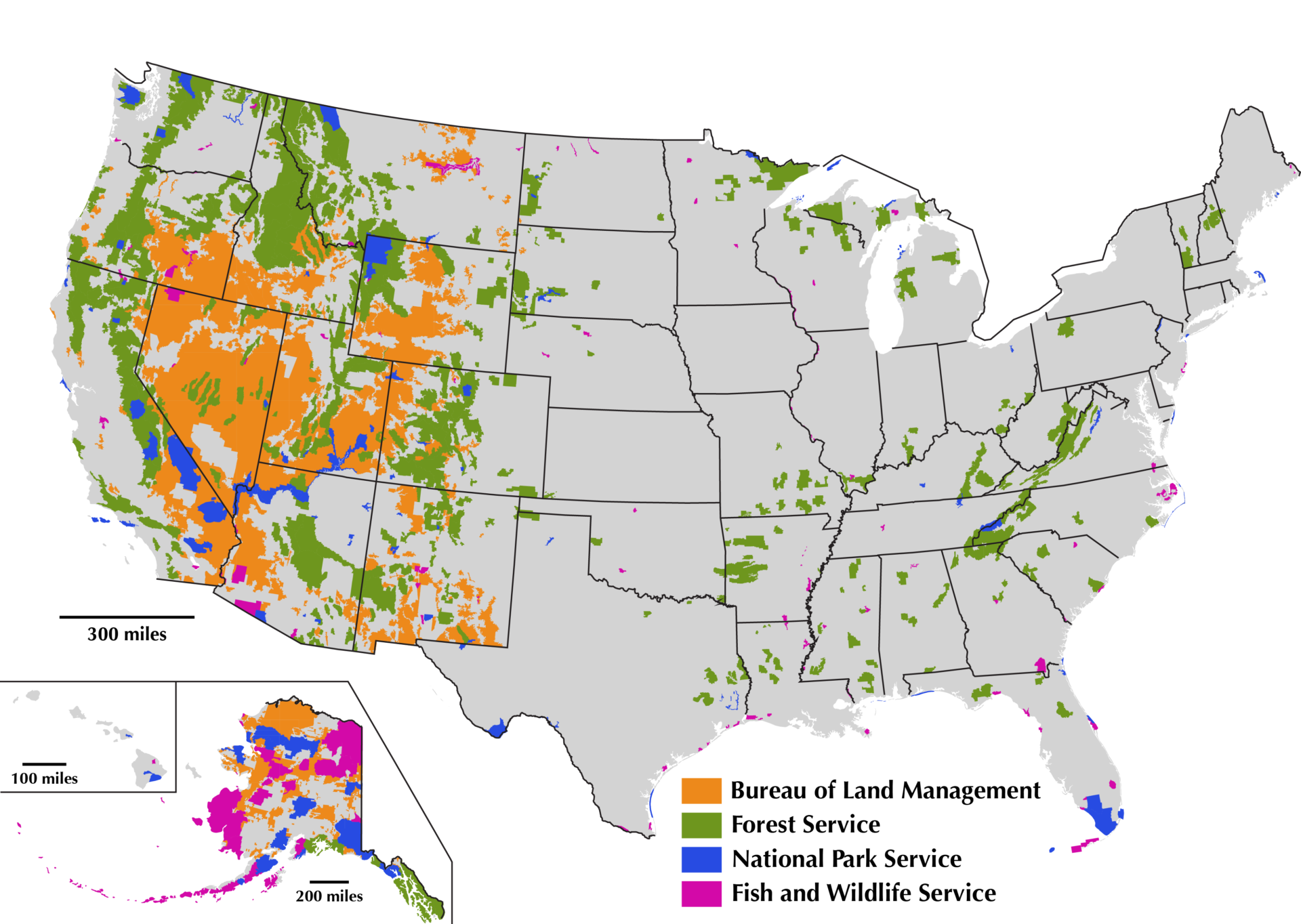

On a national scale, some 28 percent of the land in the United States is federal land. [Map 1—US Public Lands] The two biggest public lands managers are the Bureau of Land Management (BLM; 248 million acres) and the U.S. Forest Service (USFS; 193 million acres). These two agencies manage their lands, in general, to allow multiple uses. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS; 89 million acres) and the National Park Service (NPS; 80 million acres) follow more restrictive land management practices. Geographically, public lands acreage is substantial in the west, with only the USFS having large acreage in the eastern U.S.

Although my original intent was to present a narrative history of the development of public lands in these four agencies, that quickly became too much for this essay. Stay tuned for a future post! For now, I’ll share this abbreviated time line of key developments in a much larger, more complex history.

The Maps

There is nothing better than a map—except lots of maps! Having warmed you up with Map 1 showing public lands at the national scale, I offer another seven to take us through the public lands of the greater Gila Watershed. All seven maps display information on the same background map at the exact same size.

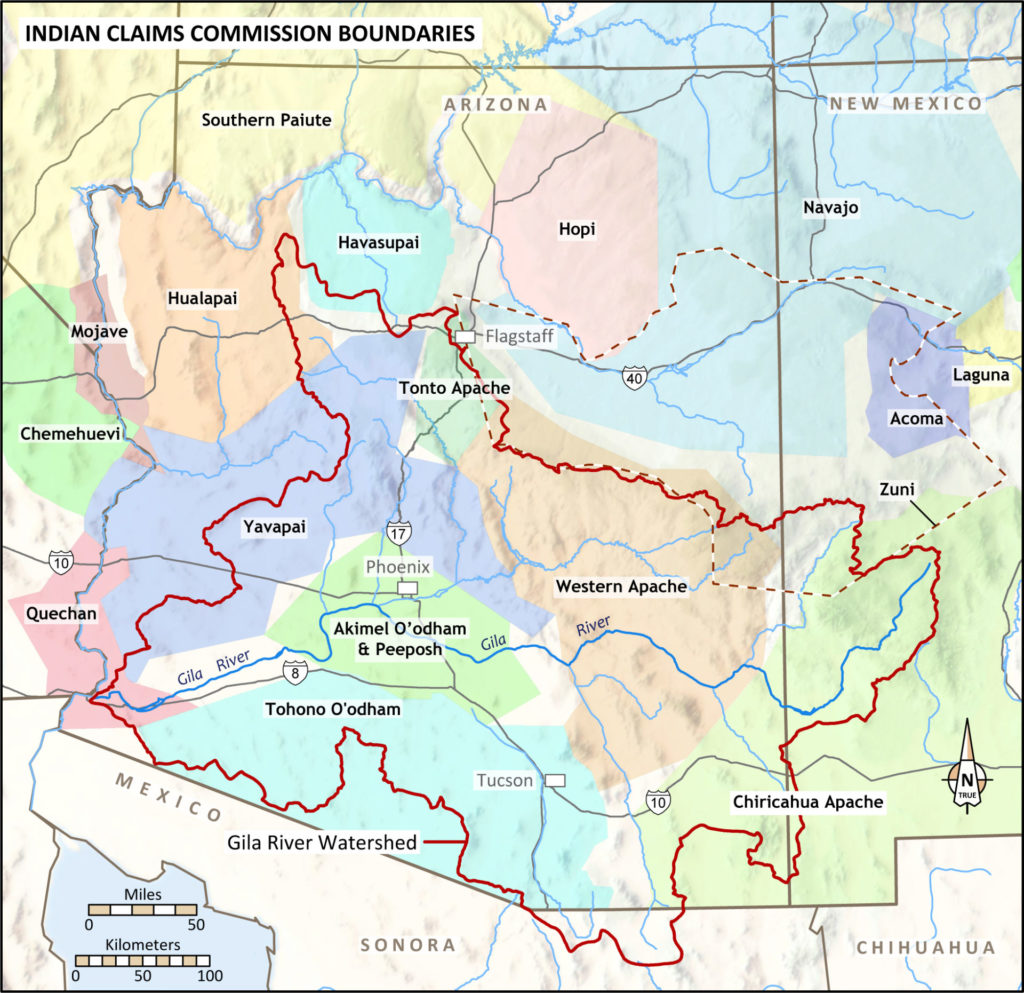

Map 2 helps to convey the tribal heritage of our Southwestern region. It displays the outcome of the Indian Claims Commission (ICC) process that extended from 1946 to 1978. One purpose of the ICC was to honor Native American bravery and service in World War II. But the primary goal was to document losses of traditional lands and to compensate tribes for their losses. Land restoration was not a consideration. Note that the mapped territories are non-overlapping, and there are empty places. The lack of overlap is obviously a bureaucratic oversimplification of a very complex situation. The plot of Zuni lands makes this point clearly. The Pueblo of Zuni did not settle with the original land claims commission. Instead, they settled in separate court cases in 1987 and 1991, and the judge accepted the area of established Zuni sovereignty in 1846 as the basis for the settlement. Note that it overlaps adjudicated territories of several other tribes. Despite the flaws in the ICC map, the nearly continuous flow of the colors does help convey that these lands were “in full use” in the past.

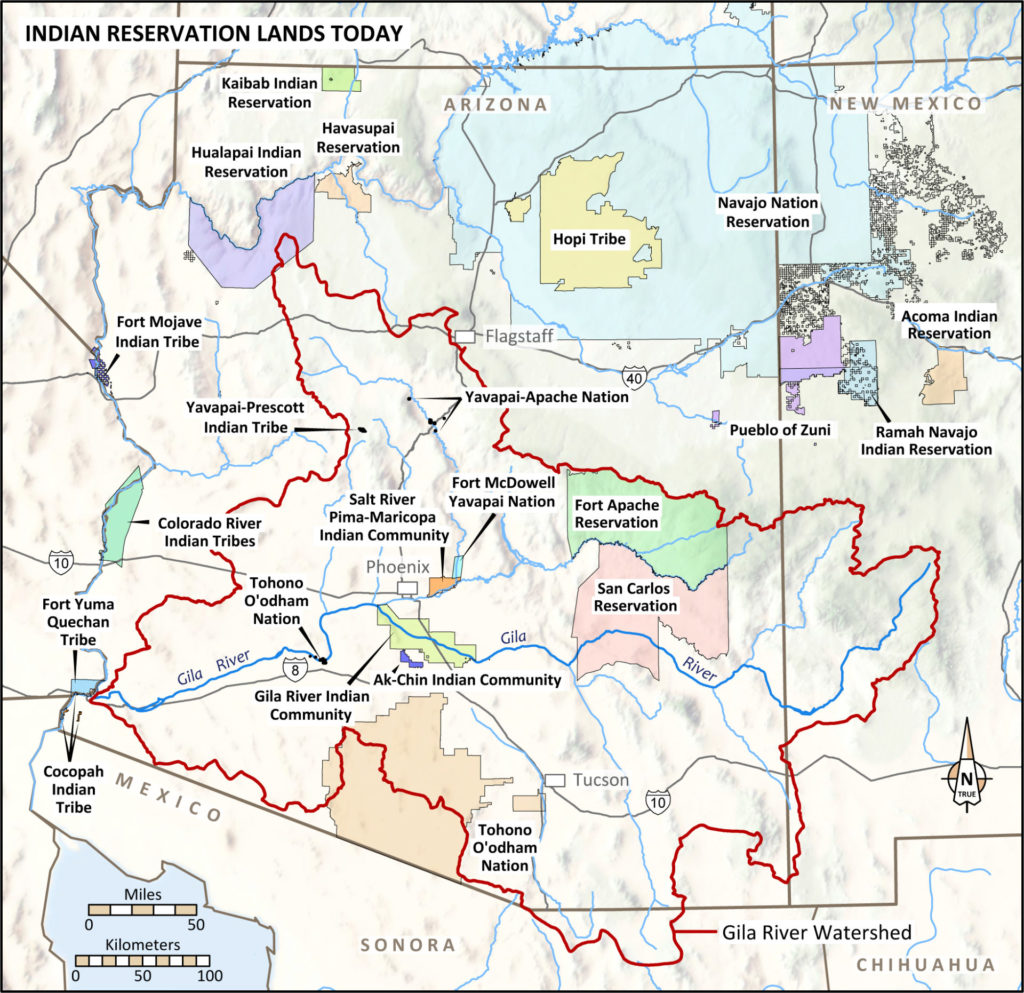

The scale of territory loss becomes evident when we look at Map 3 of current reservations. Ancestral territories were clearly much more extensive than today.

The National Parks map (Map 4) highlights the two units of Saguaro National Park to the east and west of Tucson. Not obvious is Tumacácori National Historical Park, whose three units south of Tucson comprise less than 400 acres. Both of these were originally designated as national monuments under the Antiquities Act and later elevated to national parks by Congress.

The National Monuments and National Conservation Area map (Map 5) is dominated by three Clinton national monuments (Agua Fria, Sonoran Desert, and Ironwood Forest) managed by the BLM. There are six national monuments managed by the NPS (three tiny dots in the north are Tuzigoot, Montezuma Castle/Montezuma Well). Casa Grande Ruins National Monument is a subtle area on the Gila River southeast of Phoenix; Tonto National Monument is a tiny dot on the south side of Roosevelt Lake east of Phoenix; Chiricahua National Monument is in far southeastern Arizona; and Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument is on the international border to the west. Three NCAs have been established by Congress. Two are southeast of Tucson (Las Cienegas and San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area) with Gila Box Riparian National Conservation Area located on a well-watered area of the Gila River.

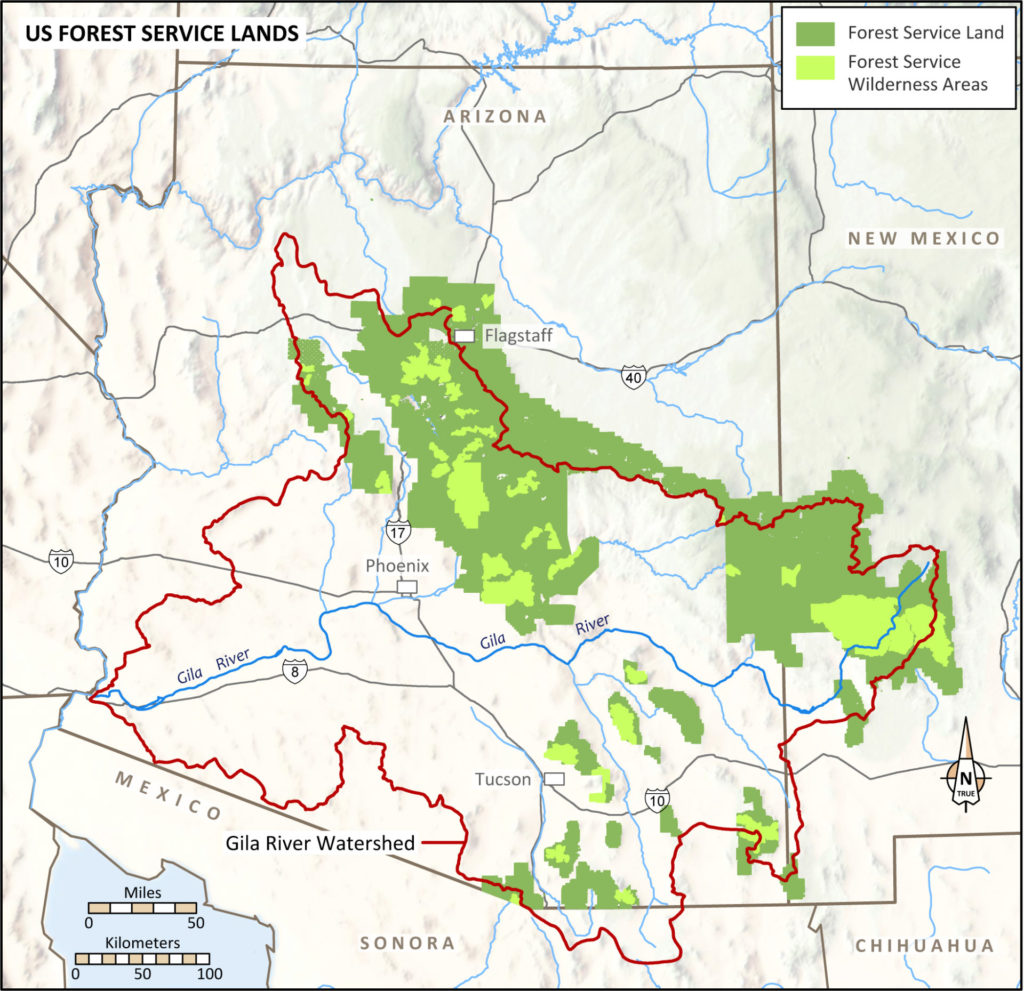

Given the point I made in the introduction to this blog series—that rainfall, temperature, and vegetation are strongly correlated with elevation in this region—it is not surprising to see USFS lands (Map 6) arrayed along the northern/northeastern portion of the Gila Watershed and in the sky islands of southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico.

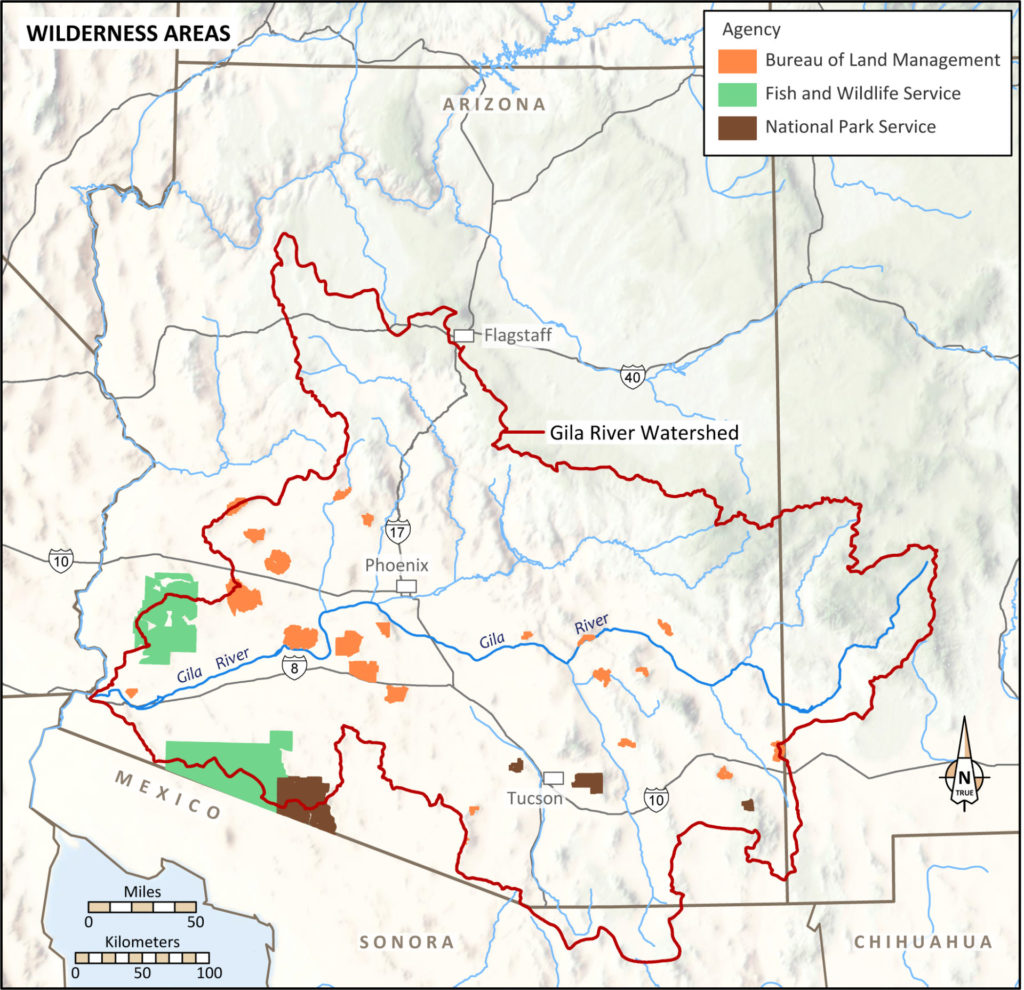

In our first Wilderness Area map (Map 7), we highlight BLM, NPS, and USFWS wilderness. Again, geography is a primary determinant of the distribution of these wilderness areas, which are mostly in lower elevations.

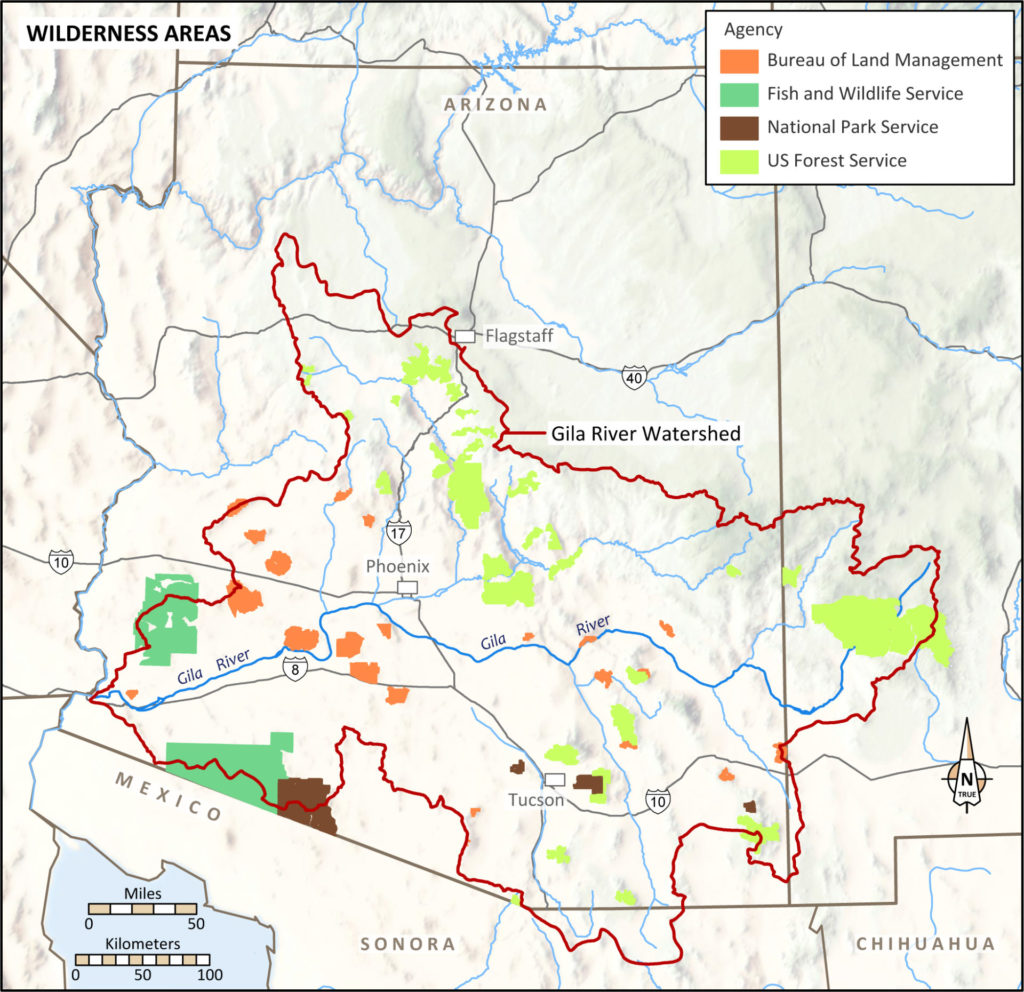

In our second Wilderness Area map (Map 8) we have pulled all of the areas onto a single map, showing a broadly dispersed distribution of wilderness.

Conclusions

These maps employ the big-picture approach that guides our Life of the Gila series. The simple goal is to convey broad themes—how public lands relate to tribal histories and modern reservations, and how the conservation lands of four government agencies are distributed across the Gila Watershed.

When you study these maps, it is important to think about the magnitude of the population that lives near Phoenix and Tucson. These urban centers have grown outward from the core zones of the ancient Hohokam cultural traditions [link]. The Phoenix metro area exceeds four million people, and Tucson is about one million. The public lands on this map series are without doubt invaluable recreational and economic amenities for the major urban/suburban concentrations of new arrivals in the region. These lands are also threatened by the scale of this growth.

Extensive areas of public land omitted from these maps are the BLM’s “regular lands”—lands that are not part of the National Landscape Conservation System (NLCS). The NLCS includes national monuments, national conservation areas, and wilderness areas managed by the BLM. At Archaeology Southwest, we do pay attention to those lands. For example, while Map 2 from the ICC above shows the lower Gila River as no tribe’s traditional territory, Aaron Wright and four Quechan field archaeologists are currently surveying BLM lands west of Gila Bend, filling in a major gap in our knowledge. And the Great Bend of the Gila National Monument proposal advocated by 11 tribes, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, Archaeology Southwest, and numerous others is focused on more than 80,000 acres of BLM land that is not part of the NLCS. (You can read more about this region here.)

It is important for archaeologists to recognize that research and preservation need to be conceived and implemented on a landscape scale. Fortunately, this consideration has been gaining traction. Our maps show that conservation lands are distributed reasonably broadly across the Gila Watershed. But only some of the conservation parcels could be considered as cultural landscapes. For example, recent tribal comments provided to the NPS in an ethnographic study focused on Casa Grande Ruins National Monument called for the agency to consider that place as part of a larger cultural landscape. A bill currently before Congress would help address that goal by expanding Casa Grande to include important related places tied to that larger landscape.

The BLM lands provide an even greater opportunity for landscape-scale preservation and interpretation. The Great Bend of the Gila incorporates fairly continuous BLM land along the river. But even in an area like the lower Gila, which is beyond the population explosion of today’s greater Phoenix, modern intrusions constrain a true landscape perspective. The pace of population growth and urban expansion are reasons to keep the discussion of public lands active. These lands can play a balancing role between the amenities of recreation and the necessities of preservation.

The above maps show the diminishment of tribal territories, with only portions of those traditional lands now incorporated in today’s reservations. The ICC process gave some compensation for the land losses tribes experienced, but a people’s heritage and sense of place isn’t something that can be bought and sold. So, in closing, I want to underscore that the public lands of the greater Gila Watershed are places where we may recognize tribal heritage, own up to past injustices, and explore opportunities for preservation, understanding, and healing.