- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Reflections on the Relevance of Weeds

Today we are pleased to share this guest post from archaeobotanist Karen Adams, our longtime member and friend. Learn more about Dr. Adams here.

(April 9, 2020)—As the world struggles to maintain normalcy in the face of a global pandemic, I am drawn to the “weeds” in our backyard. I’ve heard that “a weed is a plant with a bad press agent” (agreed), that a limited number of weeds such as “Kudzu” and “tumbleweed” are going to “take over the earth” (maybe/maybe not), and that waging war on weeds is a battle worth fighting (doubtful…as the movie Jurassic Park pointed out, “Nature will always find a way”). But, as an archaeobotanist (paleoethnobotanist) who studies plant parts from archaeological sites, I offer an alternative perspective on weeds, using two examples of weedy plants currently thriving in the vacant yards and alleyways of Tucson, Arizona: native tansy mustard and historically introduced cheeseweed.

Tansy Mustard

Tansy mustard (aka Western Tansy mustard) is an annual plant in the mustard family, widespread in the U.S. It goes by the scientific name of Descurainia pinnata (Walter) Britton, in part because of its pinnate (finely dissected) leaves. When tansy mustard plants are clustered in high populations (as in the image below), quantities of seeds are produced. In one timed experiment of 15 minutes, over a quart of seeds representing thousands of calories were gathered by two archaeologists using only beaters and baskets. The harvest also included quite a few living insects, which represented a bonus protein source, or could be left to crawl/fly away at will. The archaeologists chose to let them wander off.

As a late winter/early spring season annual, oil-rich tansy mustard seeds could be especially valuable to farming groups when agricultural products stored from previous growing seasons were used up or running low. Tansy mustard plants can be cooked up when young and tender, like a spinach, and its seeds can be parched, then tossed into stewpots and mixed into breads, or ground into a flour and made into a mush. When added to breads, the resulting product tastes like someone has added mustard to the dough.

One of the most important traits of tansy mustard seeds are the calories they contain. Efforts to harvest and quantify caloric return rates reveal that tansy mustard seeds return approximately 1,307 Kcal per hour of harvesting and processing efforts, making them an exceedingly important caloric resource. At this rate, a few hours of sustained harvesting could return enough calories for one person for one day, assuming a daily 2,000 Kcal requirement. Casual 10-minute harvesting experiments using different harvest methods suggested that beating the heads of mature plants into a nearby container to catch the seeds resulted in the greatest return (~ 40.4 grams) as did cutting the plants at the base with a knife and working the pods with fingers to release the seeds into a container (39.8 g). Stripping the plants by hand into a container produced the lowest return of only 14 g of threshed seeds. Clearly, the choice of harvest method is crucial to acquiring the greatest caloric return for the effort.

The Southwest U.S. archaeological record documents use of tansy mustard seeds in a wide variety of locations and precontact time periods. For example, these seeds have been recovered from Basketmaker II sites near Durango, Colorado, dating to 100 CE., and in Hohokam archaeological sites dating between 1100–1200 CE, as well as in Tularosa Cave in the Mogollon Culture area of New Mexico.

Likewise, the historic ethnographic record of Native American groups repeatedly reveals the collection and consumption of tansy mustard seeds by a diverse array of farming and hunting/gathering groups. These groups include the Cocopah, Gila River Pima, Havasupai, Hopi, Maricopa, Navajo and Ramah Navajo, Papago, Pima, Southern Paiute, and Yuma.

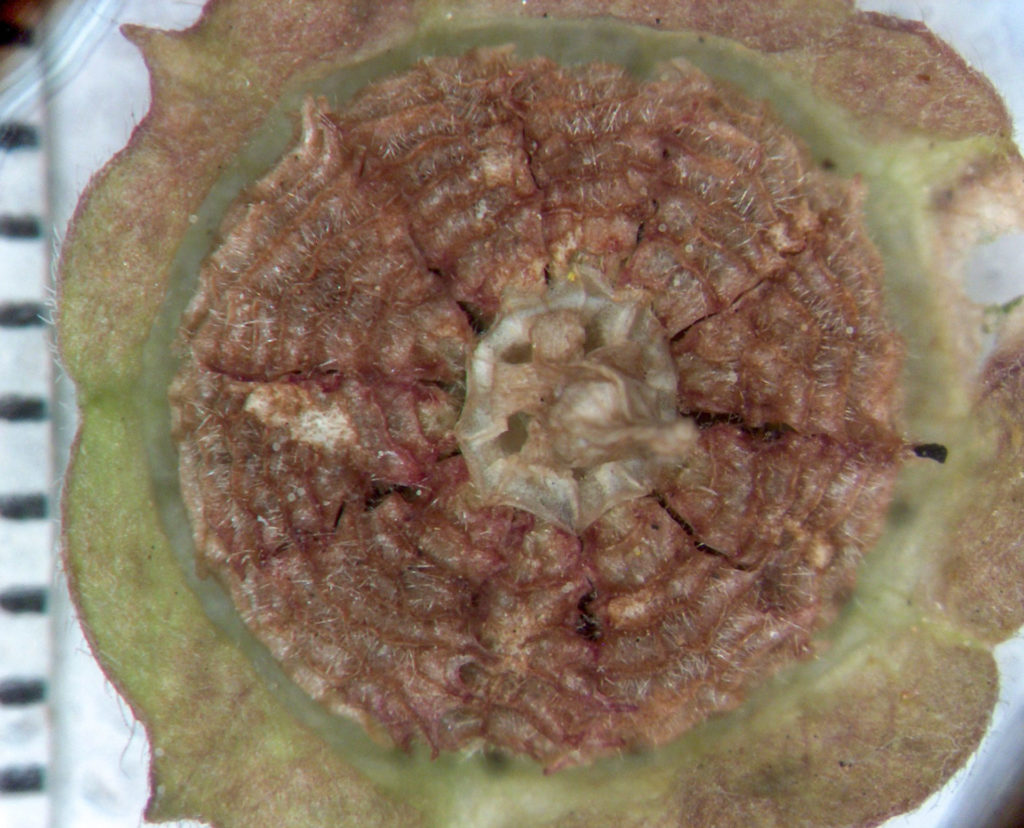

Cheeseweed

Cheeseweed, in the mallow family, is a particularly abundant springtime annual plant in my backyard and others in the U.S. Southwest. Its scientific name, Malva neglecta Wallr. (aka Malva parviflora L.), suggests it to be a plant that occupies neglected spaces. The very young tender shoots and leaves of cheeseweed have been used as a potherb in many countries. The common name describes the fruits, which look like tiny cheese wheels. As potherbs, the caloric value would have been low, like spinach, but the vitamin/mineral content would contribute important nutrients to a diet.

Evidence suggests cheeseweed was part of the great “Columbian Exchange” between the Old and New Worlds. In this exchange, wheat, oats, barley, rye, and rice were intentionally brought to the new world, while other plants inadvertently came along for the ride…such as tumbleweed (Salsola kali) from the Russian steppes, Kochia (Kochia scoparia) from Eurasia, cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) from Europe, Southwest Asia, and North Africa, and cheeseweed. Of course, the New World gave corn (Zea mays), beans (Phaseolus spp.), and squash (Cucurbita spp.) to the rest of the world. Once considered a food in the New World, cheeseweed is now relegated to the status of a pesky weed.

Further Reading:

Adams, Karen R.

1980 Pollen, Parched Seeds and Prehistory: A Pilot Investigation of Prehistoric Plant Remains from Salmon Ruin, A Chacoan Pueblo in Northwestern New Mexico. Eastern New Mexico University Contributions in Anthropology, Vol. 9, Portales, NM.

Ebeling, Walter

1986 Handbook of Indian Foods and Fibers of Arid America. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

Huckell, Lisa W., and Mollie S. Toll

2004 Wild Plant Use in the North American Southwest. In People and Plants in Ancient Western North America, edited by Paul Minnis, pp. 37–114. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C.

Rainey, Katharine D., and Karen R. Adams

2004 Plant Use by Native Peoples of the American Southwest: Ethnographic Documentation [HTML Title]. Available: http://www.crowcanyon.org/plantuses. Date of use: 01 April 2020.

Shulman, Nancy, Vandy E. Bowyer, Malaina Brown, and Karen R. Adams

1995 Mustard seed (Descurainia sophia) gathering experiment, June 30, 1995. Manuscript on file, Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, Cortez, CO.

Simms, Steven R.

1987 Behavioral Ecology and Hunter-Gatherer Foraging: An Example from the Great Basin. BAR International 381, Oxford.

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.