- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Focus on the Field Crew: Zion White

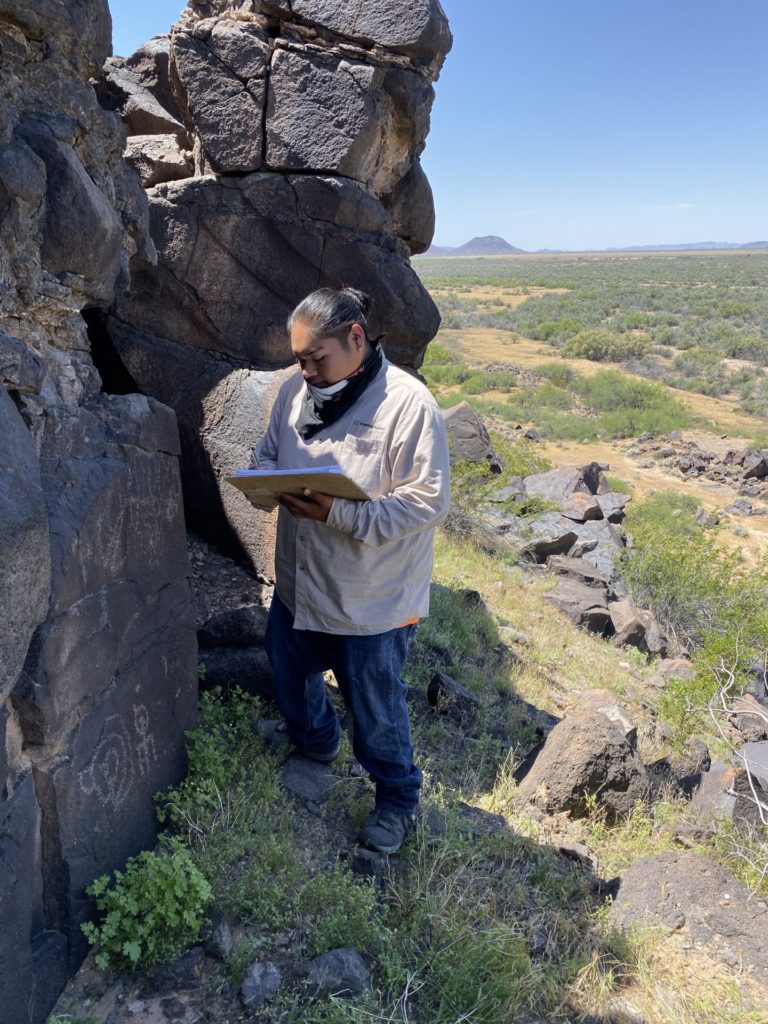

(April 24, 2020)—Over the past two weeks, I’ve shared the voices and perspectives of Keahna Owl and Charles Arrow, two of the four members of the Lower Gila River Ethnographic and Archaeological Project’s (LGREAP) 2019–2020 field crew. In this third installment of Focus on the Field Crew, I introduce Zion White, or “Z,” as we tend to refer to him. Zion is a member of the Fort Yuma Quechan Indian Tribe, and when I first met him at the beginning of our field season, he was the newest member of the Quechan Cultural Committee. And at 20 years old, he was also the youngest.

Zion’s interest in Quechan heritage and history is multifaceted. From what I’ve gathered through conversation, he is an accomplished Bird Singer and dancer, which amazes me because of the many hours and years of practice and participation he has devoted to these traditional practices. On several occasions I’ve had the honor and privilege to hear him sing social songs accompanied by his gourd. And although I still don’t fully understand the rules and customs of the game, Zion is also an avid peon player. Peon is a version of hand game played by many of the southern California tribes. Often, at the beginning of our work week, I get a synopsis of the weekend’s peon tournament—which community hosted, who won, etc. As you’ll read here, LGREAP has provided Zion with an archaeological experience to accompany his study of Quechan oral history, language, dance, and song.

Aaron: Could you tell me what your first memory or experience with archaeology was?

Zion: So, my first experience with archaeology was probably, when I was younger, going out with relatives like my mother and uncle, who was a medicine man, and we’d collect these lava rocks to use in ceremonies, for sweat lodges. And in that area we saw sherds and things like that. So while collecting those lava rocks I had my first experiences with archaeology. Also as a child, I had the opportunity to see the King Tut archaeology exhibit, which really instilled an interest.

Aaron: So, with that background, what attracted you to this current project?

Zion: I heard about this project through my tribe, and it seemed interesting about what we’d be doing because it’s right in our direct ancestral territory. It would be an opportunity to learn about my own ancestral territory. So, it’s really cool to be on the project and being able to research locations that are directly related to my tribe.

Aaron: How has your perspective on archaeology changed from when you first began the project ‘til now?

Zion: My perspective has probably changed…it has changed from when I started the project because I’ve learned new surveying techniques when archaeology is mainly portrayed as digging. It’s really amazing to see all of the things that we do on the surveys, like sherds, trails, projectiles, and the petroglyphs. Some of these are connected to my tribe, seeing the designs that we still use today. It gives me a greater respect for being in the area that I’m in.

Aaron: What do you find to be the most interesting aspect of this project?

Zion: One of the most interesting aspects of the project is having to be away from family for most of the week. I’m there with just the survey crew and it’s brought me closer to the group of people that I’m working with, and I enjoy being out there.

Aaron: How does this project compare with other types of archaeological research you’ve read about or learned about elsewhere?

Zion: The way this project, I believe, compares is that it is unique because not much modern research is available on the areas we’re surveying. So, hopefully this will be a fresh perspective on what still remains. It’s good to be part of the work because it’s work that I haven’t seen a lot of. I don’t know that much about the area that I am in, so doing archaeological research into my tribe, even though I know my culture and history, but actually being out there and being able to see it in this area is really nice.

Aaron: What do you see as the value or the long-term benefit of the project, in general?

Zion: I think the long-term benefit of the project is it’s going to give people a greater understanding of what is out there and what needs to be protected. It will hopefully give others in the Indigenous community a yearning to want to know more about their direct territories through archaeology.

Aaron: In what ways do you see archaeology contributing to the preservation of Quechan traditions and heritage?

Zion: I think the research we’re doing right now is going to influence people to be more involved in the culture that we still have, the sites that we still have to protect. And I think people are going to just want to know more. The preservation of these sites and artifacts will give Quechans insight on what our people left behind and what ultimately needs to be protected.

Aaron: What aspects of Quechan history and tradition are we not able to access through archaeology?

Zion: Aspects of Quechan history we’re not able to really see through archaeology include the rich history of song and ceremony, which our people still carry and practice today. We see one aspect of culture through things that are left behind, but the things such as songs and ceremony that are still practiced, are something we can’t see through archaeology. But seeing the places that we’re at and seeing the things that we do, I believe without a doubt that some of these places were used for ceremony. Seeing things like that gives me greater respect for being Indigenous.

Aaron: How do you think research and the conservation of archaeological sites and artifacts contributes to the teaching and preservation of traditional Quechan culture and heritage?

Zion: As the landscape changes, so will these sites and artifacts, and if research isn’t done now on what is still out there then there will be nothing to protect in the future. I definitely think research like this will give people opportunity to learn about things in the future. You know, some people tend to think they have time to learn about these things, but if these things aren’t protected then they won’t have the opportunity to learn about their culture.

Aaron: How does Quechan oral history and stories, how do they compare with the archaeology of the lower Gila River where we’ve been working? Are they compatible, and if so, how?

Zion: I think Quechan history and the area that we’re in right now are compatible because we do see designs, particularly in petroglyphs, that we still use in our regalia today. So that’s a testament that we were there in that area, and these areas were used to go back and forth to spiritual places. These places that we’re in are ultimately, we believe, going to be in the afterlife. If we don’t protect them, then we won’t have a way to get back to them.

Aaron: Is there anything about the landscape that speaks to the history of interaction with the tribes upriver, say the Maricopas [Piipaash] or Pimas [Akimel O’odham]?

Zion: Yes, I believe the areas that we are in do connect with the other tribes because of the distinctive artifacts that have been left behind, and we’re able to distinguish and differentiate between the different cultures. What speaks to the interaction between these tribes is the discovery of artifacts of distinctly different cultures in the same site area. And connecting the two really confirms the fact that these are places we were fighting over and are worth protecting now.

Aaron: How well do you think archaeologists and anthropologists, in general, have listened to the concerns and interests of Native communities in the past?

Zion: I don’t know if the surveys were governmental or archaeological, but as far back as Ward Valley, that’s in my lifetime [read more on the Ward Valley Occupation here]. I was alive when that was happening. My mother was on council, and she had quite a big part in our tribe’s and other tribes’ along the Colorado River efforts to stop the nuclear waste facility from being built. I believe that that should not have taken place; something like that should not have been built. I also think we’ve seen in recent years with the Dakota Access Pipe Line Indigenous people still have to protest to protect our land.

Aaron: Do you believe Indigenous communities should have more of a role in archaeology, and why?

Zion: I think Indigenous communities should have a greater role in archaeology because it directly affects them being…that because…they’re Indigenous to the land they’re on. After being on this project, it gives me insight and perspective on the land that I stand on, and gives me greater respect for it and for being Quechan.

Aaron: Is there anything about our fieldwork that has fostered in you a closer connection to Quechan history?

Zion: I think being on the project has definitely inspired me to learn more about my culture, especially language and learning more songs and being more immersed in the culture. Our field work has fostered a closer connection with being Quechan because, before starting our fieldwork, we were using the designs we see in the petroglyphs. Seeing those same designs on the cliffs we survey gives me the utmost respect in being a Quechan Native.

Aaron: Now, you’re a traditional singer. Your singing, does that inspire the work that you do in archaeology right now, or does the archaeology that we’re doing inspire your singing, or both?

Zion: I think they definitely go hand in hand, the singing and archaeology. While singing, in my mind’s eye I’m back to those places I see on our surveys, which are places where my ancestors traveled. Being in the places that we’re at, seeing the things that were left behind…again, I believe these are places of ceremony and are places to be respected. When I come back it gives me a greater respect for just being at home, on our reservation. I’m blessed enough to still be on ancestral territory and not displaced.

Aaron: How would you like to see archaeology carried out in the future?

Zion: I’d like to see more active involvement from Indigenous communities in archaeology, with projects that go on in that area and surveying ancestral territory that they’re able to. It’d give them greater insight into their communities.

Aaron: How has your experience on this project shaped your future goals?

Zion: Being on the project shaped my future goals in that I want to know more about my culture, like my language. I’d also definitely like to be certified as a tribal monitor or a CRM [i.e., cultural resource management] position.

Aaron: So, do you envision yourself then continuing in archaeology, whether that be through school or employment, or maybe just even community advocacy?

Zion: I can see myself continuing with archaeology whether that be through school or in the community to find out about what’s out there in my direct location, being on my tribe’s ancestral territory and reservation. Being on the project has given me a passion for it that won’t fade.

Postscript: In last week’s Focus on the Field Crew, Charles Arrow lamented the loss of Quechan tradition, culture, and language due to forces of modernization and “lost interest.” He is certainly right, as the survival of cultural heritage is something practically all Indigenous communities say is persistently threatened from many different angles. When I engage with tribal communities on heritage matters in southern Arizona, I usually interact with elders, because they are the ones versed in tribal history and traditional cultural knowledge and have the authority to speak on such matters. In our conversations, they sometimes remark on a general disinterest in heritage issues among the younger generation.

The LGREAP field crew demonstrates that there are exceptions. This is particularly true of Zion White, whose dedication to traditional Quechan practices and commitment to service on the cultural committee and seven months of fieldwork through LGREAP—all at the age of 20 (now 21)—are beyond admirable.

This three-year study was awarded a Collaborative Research Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (RZ-255760). The NEH is an independent federal agency created in 1965. It is one of the largest funders of humanities programs in the United States and awards grants to top-rated proposals examined by panels of independent, external reviewers. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this study do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.