Archaeology Southwest, in partnership with the Santa Cruz Valley Heritage Alliance, is pleased to support the newly designated Santa Cruz Valley National Heritage Area. This congressional designation honors, preserves, and celebrates the region’s diverse natural resources and cultural contributions. To learn more about Archaeology Southwest’s participation in National Heritage Area designation efforts, including this one, visit here.

While the Santa Cruz Valley Heritage Alliance is updating their website, Archaeology Southwest is offering this page to coordinate the Request for Proposals (RFP) for the Santa Cruz Valley National Heritage Area Management Plan.

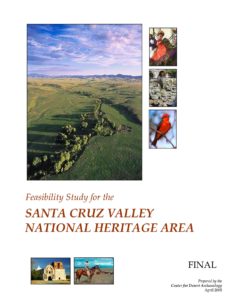

To learn more about the Santa Cruz Valley National Heritage Area, download and read the Feasibility Study for the Santa Cruz Valley National Heritage Area (opens as a PDF). View a map of the Santa Cruz Valley National Heritage Area boundaries here (opens as a PDF).

From the preface of this report:

The proposed Santa Cruz Valley National Heritage Area is a big land filled with small details. One’s first impression may be of size and distance—broad valleys rimmed by mountain ranges, with a huge sky arching over all. However, a closer look reveals that, beneath the broad brush strokes, this is a land of astonishing variety. For example, it is comprised of several kinds of desert, year-round flowing streams, and sky island mountain ranges. Even Tucson, with its late twentieth century urban sprawl, is much more than a lot of suburbs in search of a city. Our natural history is examined first. There is the Upper Sonoran Desert, with its many varieties of cactus—tree-like chollas, barrel cactus, low-lying hedgehogs and pincushions, green and purple prickly pears, and, of course, the towering, columnar saguaros; there are desert grasslands, and 90 miles of year-round flowing desert streams; there are oak woodlands, and pine-covered mountain ranges that are often snowy in the wintertime. Each area, of course, has its year-round and seasonal birds and animals. There are spadefoot toads who live most of the year underground, and only come out to mate (and sing about it) during the summer rains. There are migratory birds to give joy to the birdwatcher. There are the coyotes, javalinas, deer and mountain lions who live here all year, and the occasional jaguar visiting from south of the border. And there are the enerable human institutions, such as Coronado National Forest, Tumacácori and Saguaro national parks, Tohono Chul Park, and the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, whose job it is to interpret our natural history for resident and visitor alike.

This is also a land of persistence and continuity. People have been growing crops in the Santa Cruz Valley for about 4,000 years. Many of the crops that developed here—including specialized varieties of corn, beans, and squash—are still grown in the region. When Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, S. J., arrived here in the 1690s, bringing European culture with him, he met folks who called themselves O’odham—the People. There are still O’odham here, speaking their own language, following their own cultural traditions. However, the language and culture Father Kino brought with him are also still important in the region. One can visit four eighteenth century Spanish missions—three administered and interpreted by the National Park Service, and one a functioning Catholic church to this day, serving the native village for which it was built. This last church, mission San Xavier del Bac, is perhaps the most complete eighteenth century Spanish Colonial baroque church in the continental United States. With few exceptions, everything that was in the church at the time of its dedication in 1798 is still there.

There are other living traces of our Spanish Colonial period. When Father Kino came into this country, he brought with him beef cattle and wheat seeds. It is no accident that wheat flour tortillas and beef (and, of course, cheese) comprise a vital part of the local native and Mexican diet, and dominate the menus of local Mexican restaurants. Families whose ancestors first came here in 1776, to form Spanish military garrisons still live here, as do some of the native families who watched them arrive. Both of their languages are still spoken here, as is the Yoeme (also known as Yaqui) language, brought here from Sonora in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. There are four Yoeme communities in and near Tucson that preserve an annual seventeenth century passion play to which visitors are welcomed.

Many of the occupations that were brought by the early Spanish settlers are still important in the region. Tucson was founded as a military presidio or garrison; the remains of an earlier such outpost may be seen at nearby Tubac Presidio State Historic Park. Old Fort Lowell in Tucson reminds of the nineteenth century and the Apache Wars, while the Titan Missile Silo in Sahuarita and the remarkable collection of older military airplanes at the Pima Air and Space Museum and the “boneyard” at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base bring us into the twentieth century. Father Kino brought the first cattle into the area in the 1690s, and cattle raising is still important here. Much of the Santa Cruz Valley is still ranching country, and the Empire Ranch at the eastern border of the area does an excellent job of interpreting traditional cattle ranching for visitors. A stroll through one of our rural cemeteries will reveal crosses and other monuments made of horseshoes, which make the clear statement: “a cowboy is buried here.” Mining of precious metals has been important in the area for as long as Europeans have been here, and here, too, are traces of older and more recent activity. The area’s several ghost towns, along with the towering waste dumps of modern mines that form the western edge of the Santa Cruz Valley, stand as witness to our never-ceasing search for minerals. Start asking any long-term resident about local lost mines and buried treasures, and you may well hear some of the great stories that have flourished here for well over 100 years. However, the stories themselves are the real treasure—in most cases, the gold simply is not there, and digging for it on either private or public land is strictly discouraged.

So this is the region covered by the proposed Santa Cruz Valley National Heritage Area. It is important to remember that many of the same characteristics exist on the Mexican side of the border. The most important characteristics of the area may be seen as diversity and persistence…with the addition of subtlety. There is so much more here than immediately meets the eye, that coordinated interpretation efforts are vital to imparting an understanding of our country. And with understanding can come the kind of respect and love of the land, its traditions, and its occupants, that we who propose this designation share.

—Jim Griffith, December 2004

Details

Related to This

-

Project Tucson Origins

-

Project National Heritage Areas