- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- A Brief Cultural History of Mesquite

(June 12, 2020)—Since moving to Tucson, I find June to be a welcome time of transition. The atmosphere shifts from hot and dry at the beginning to, well, hotter, but not so dry by the end as the summer monsoon sets in. Usually as the spring semester at the University of Arizona wraps up (not this year due to the pandemic), many students abruptly leave for the summer. That, combined with the fact that it’s just too darn hot to be milling about outside during midday hours, makes June-time Tucson, a city with a half-million residents, seem like a veritable ghost town.

But the most interesting change for me is the move from flowers to fruits on two of the most important native food sources in the Sonoran Desert—saguaro and mesquite. These foods were once so important that the Tohono O’odham lunar calendar designates a month to each of them. In early June, we find ourselves in U’us Wihogdag Masad, “Mesquite Bean Harvest Moon,” and by the end of the month we enter Ha:san Ba:k Masad, “Saguaro Fruit Ripening Moon.”

Here I focus on the first of these to ripen around Tucson—mesquite. And while you’ll find this post long, quite longer than we usually share on the Preservation Archaeology blog, it is in keeping with how life seemingly slows and changes here in the summer. And I suspect longer reads are a little more welcome these days.

Mesquites of the Southwest

Five species of mesquite (Prosopis spp.) are native to the Greater Southwest. Honey mesquite (P. glandulosa) is the most widespread, as its range stretches from the Pacific Coast to the Gulf of Mexico. The range of velvet mesquite (P. velutina) is more narrowly confined to the International Four Corners (southern Arizona and New Mexico, northern Chihuahua and Sonora).

Screwbean mesquite (P. pubescens) is widely distributed as well, but more confined to the damp, saline soils found in southeast California and along the watercourses of the middle Rio Grande and lower Colorado River and their low-elevation tributaries. “Screwbean” owes to the fruit’s peculiar resemblance to a screw. Another species, tornillo (P. reptans), is more localized to southern Texas. Because it shares the screw-like appearance of P. pubescens, you may hear it referred to as dwarf screwbean.

The fifth indigenous species is palo de hierro (P. palmeri), whose range is restricted to southern Baja with sporadic occurrences across the Gulf of California in Sinaloa.

Chilean mesquite (P. chilensis) is a sixth species of mesquite presently found within the Greater Southwest, but it is not indigenous to this continent. As the name implies, Chilean mesquite is native to the arid environments of Chile, Argentina, and Peru. It is popular for landscaping because it grows quickly and lacks thorns, but it is a relatively recent addition to the Southwest’s biome. Hybrid varieties that mix Chilean and native species are also present.

Southwestern Mesquite Culture

Indigenous communities of the Greater Southwest found many, many uses for mesquite.

They used the tree’s strong but sinuous roots in basketry and other forms of weaving. People found the hearty wood useful, of course, but the sap was handy, too. They made varieties of candies from it, and some even chewed it as a sort of gum. The sap’s stickiness also allowed people to use it as an adhesive. Some applied it to baskets to make them watertight.

Mesquite also factored into a number of medicines and practices. Some healers applied the sap as a protective coating on lesions or chewed the leaves and placed the mass on stings to alleviate pain and swelling. Some Kewevkepaya (Southeastern Yavapai) even used the sap as hair dye. During ceremonies associated with ritual racing, some Opata of Sonora smoked a peculiar fungus that grows on mesquite trees.

Not surprisingly, mesquite is an indicator of groundwater conditions. Certain communities like the Cahuilla sited wells in dry desert valleys based on the presence of mesquite.

As a Southwestern archaeologist, I must invoke pottery in any discussion, including one on mesquite. Why? Well, Southwestern potters often painted their wares. Much Mogollon and Ancestral Pueblo pottery is adorned with black-painted designs. To achieve black, potters used an iron-rich mineral paint, an organic paint, or a combination thereof. These pots had to be fired in either a neutral or reducing atmosphere, meaning just enough (neutral) or not enough (reducing) oxygen was introduced during the firing to burn the fuel. When pots were fired in an oxidizing atmosphere, where there was excess oxygen, the paints would oxidize and typically turn red (iron-rich mineral paint) or burn off (organic paint).

In southern Arizona, most Indigenous potters fired their wares in oxidizing or uncontrolled atmospheres where the vessels were exposed to variable amounts of oxygen. This oxidization is what created the red complexion to Hohokam painted (i.e., red-on-buff) and slipped (i.e., red ware) pottery. O’odham, Piipaash, and Cocopah potters have traditionally fired their wares in oxidizing environments, too, but they decorated some of their pots with black line work. How?

Potters boiled mesquite sap to create a paint that they applied after firing the pots. Once applied, they re-fired the pot at a lower temperature and for a shorter duration so as to not oxidize the mesquite paint. When applied, the mesquite pigment was faint and hard to discern, but the re-firing brought out the paint’s deep black hue. When applied to the scummy cream-to-white surface on buff-firing clays, where the creamy surface derives from salts within the clay, this southern Arizona pottery effectively resembles the black-on-white slipped pottery of northern Arizona and New Mexico, although the designs are quintessentially O’odham and Yuman.

Mesquite as Food

It may come as a surprise that mesquite trees are legumes, in the same biological family (Fabaceae) as beans and peas. When I share my fascination with mesquite as a food source, I am often met with looks of bewilderment—until I explain that I eat the pods, not the wood.

For many people, the culinary experience with mesquite begins and ends with barbeque, because the wood is a popular way for imbuing a smoky flavor to meats. I admit that, until I moved to the Sonoran Desert, my familiarity with mesquite was limited to barbecue-flavored potato chips. I quickly learned, however, that an understanding of mesquite was critical to understanding Indigenous Sonoran Desert people, past and present.

Where it is found, mesquite was one of the most significant dietary staples for Indigenous communities of the Sonoran, Chihuahuan, and Mojave Deserts. Ethnobotanists Willis Bell and Edward Castetter suggested mesquite was the principal source of wild food for people living along the lower Colorado and Gila Rivers even though those very people were accomplished agriculturalists. They indicated further that it may have been the most important component of their diets, even more so than maize, until quite recently. Writing in 1871, Frederick Grossman, the Bureau of Indian Affairs agent stationed at the Gila River Indian Reservation near Phoenix, stated that the Akimel O’odham and Piipaash communities there gathered millions of pounds of mesquite pods annually! In a good year, I might gather 80 pounds, most of which I give away to friends. A little goes a long way.

People consumed mesquite in many ways. In the spring, they would occasionally eat the flowers before they fruited, but sources are unanimous that the ripe pod was the most desirable part. For all varieties except screwbean, people processed the pods immediately or kept the whole pods in granary baskets on their roofs or in specially designed granary rooms to keep them safe from vermin until they were needed and ground. Typically, people ground the pods into a flour for use in solid foods, but sometimes they ate them whole, or boiled them into a beverage. Early colonial diarists often referred to mesquite flour as pinole and mesquite-based beverages as atole.

In some instances, people cooked the pods with animal flesh and ate them together. By grinding the pod, they were able to pulverize the pith (or mesocarp), but the little black seeds inside are too hard to reduce with typical grinding tools, and are consequently indigestible. People would either leave these seeds in the flour or winnow them out. Separated, the seeds could be parched over a fire, which made them brittle enough to be ground into flour, as well.

To process screwbean mesquite pods, people usually needed to “cook” them for a period of time before they took on their desirable brown and sweet character. To do so, people placed them in a damp pit lined with arrowweed for several days to weeks, after which they removed the pods, dried them, and ground them as they would the other mesquite varieties.

Once ground, people could save the mesquite flour for many years by adding a bit of moisture to it until it formed a hard, shelf-stable cake. The Tohono O’odham once called these “mesquite turtles.” When people needed the flour, they would break the cakes and soften the pieces by rehydrating in water. From the dry flour, people made a variety of dense, cake-like breads that others have described as tortillas, loaves, mush, pancakes, and dumplings, depending on their softness and how they were cooked. Sometimes cooks mixed the flour other edibles—the flour of corn and wheat, seeds, cactus fruits, even agave—to add even more variety to their mesquite cuisine.

Alternatively, people consumed the pods as a liquid, by either boiling them or adding flour to water. They would also reduce this liquid to thicken it into substances that some have described as gruel and pudding. People would also, on occasion, allow the liquid concoctions to ferment into beer- and wine-like beverages.

If you are curious about what mesquite pods taste like, I encourage you to try them. Each tree is different—there is a sort of terroir to mesquite. Sweet and nutty is common, which is probably why the colonial diarists referenced mesquite foods as pinole and atole (slightly sweetened yet savory foods popular in Mexico). Personally, I’ve tasted undertones of honey, citrus, apple, and even cacao in trees around Tucson. While volunteering with Desert Harvesters several years ago, I learned more about mesquite from Clifford Pablo, a tribal elder with vast traditional knowledge of mesquite who teaches at Tohono O’odham Community College’s Agricultural Extension. Among other things, he shared with us that pods with purple streaks tend to be sweeter.

All of this applies to the native varieties, but not the Chilean imports and hybrids of them. Their pods are often astringent, bitter, and chalky. Nevertheless, on occasion, I’ve tasted Chilean pods with a not-so-terrible flavor and texture. One lesson I’ve learned is that you can never judge a pod by its complexion; you must taste it to know its true nature.

Aside from being delicious, the other reason mesquite pods were so important to the Indigenous diet is their nutritional profile. As the composition of honey mesquite in the table below shows, they are rich in carbohydrates and fiber, and if you can grind the seeds along with the flour—which is now possible with mechanized mills—you double the available protein. And nutritionists consider the glycemic index (GI) of mesquite pods incredibly low relative to most other flours, meaning it is much better for regulating blood sugar levels (25 GI compared to 75 GI for whole wheat flour). In a nutshell (or pod?), mesquite is simply a deliciously health food.

| Approximate Composition of Honey Mesquite Pods | |||

| Pith Only | Seed Only | Whole Pod | |

| Moisture | 8.0% | 6.4% | 8.4% |

| Protein | 5.2% | 40.5% | 10.6% |

| Fat | 2.8% | 4.9% | 3.5% |

| Carbohydrate | 88.6% | 51.0% | 82.3% |

| Ash | 3.4% | 3.5% | 3.5% |

| Crude Fiber | 30.4% | 6.7% | 26.0% |

| Adapted from Nutritional Evaluation of Honey Mesquite Pods and Seeds, 1984, Reza Zolfaghari, Ph.D dissertation, Home Economics, Texas Tech University, Lubbock. | |||

The Archaeology of Mesquite, with Some Hands-On Experience

One would think that if mesquite was so important to the Indigenous diet in the recent past, then it would be so in ages past, as well, and we would see evidence of it. This is mostly true. The archaeological record only contains material that preserves; it is far from a complete account of what people did, what they valued, who they loved, how they believed, and everything else that makes them human.

Archaeologists rarely recover actual foodstuffs of mesquite. This is partly due to the fact that people ate them, and also because they are organic and tend to decompose. We are therefore left with the parts that do not decay so easily and the tools used specifically for processing mesquite pods. Archaeologists have found mesquite pods in certain contexts conducive to their preservation, but most often we recover the little black seeds that are difficult to process and often discarded. We also commonly find mesquite pollen in archaeological contexts in southern Arizona, and we recover bits of mesquite bark, pods, and seeds in flotation samples.

At the Hohokam settlement archaeologists call Snaketown, archaeobotanist Vorsila Bohrer examined macrobotanical remains from Emil Haury’s second excavation there in the mid-1960s and found remarkable correspondence in the types of seeds in the archaeological refuse with the range of wild plants used by the Akimel O’odham, including mesquite. In fact, she found that the hard-to-grind mesquite seeds, presumably removed from the pods during the grinding process, accounted for two-thirds of all seeds in the village’s trash.

This finding of the prevalence of mesquite pod residue at Snaketown is quite insightful, considering that the village’s residents, as canal-based irrigation agriculturalists, were heavily invested in farming maize. Archaeobotanist Bob Gasser showed that this was not unique to Snaketown, but that mesquite is usually one of the top three or four plant taxa (scientific groups) recovered from Hohokam villages everywhere. The historically witnessed pattern where mesquite rivaled and possibly surpassed maize as the principal staple in the diets of riverine agriculturalists in the Sonoran Desert is probably applicable to Hohokam and some Patayan and Mogollon contexts, as well.

Anyone who has spent much time hiking around the Sonoran Desert has probably found at least one bedrock mortar. Mortars are circular in plan view, most often deeper than they are wide, with vertical or near-vertical sides. Although archaeologists tend to regard these holes as a form of ground stone, akin to metates and manos, you’ll find—if you feel the inside of one—that they aren’t very smooth. And there is little evidence of grinding. Turns out, people most often used bedrock mortars for pulverizing seeds, fruits, and minerals, which required a crushing motion more so than an abrasive, grinding one. In California and beyond the range of mesquite, people relied on bedrock mortars to process acorns.

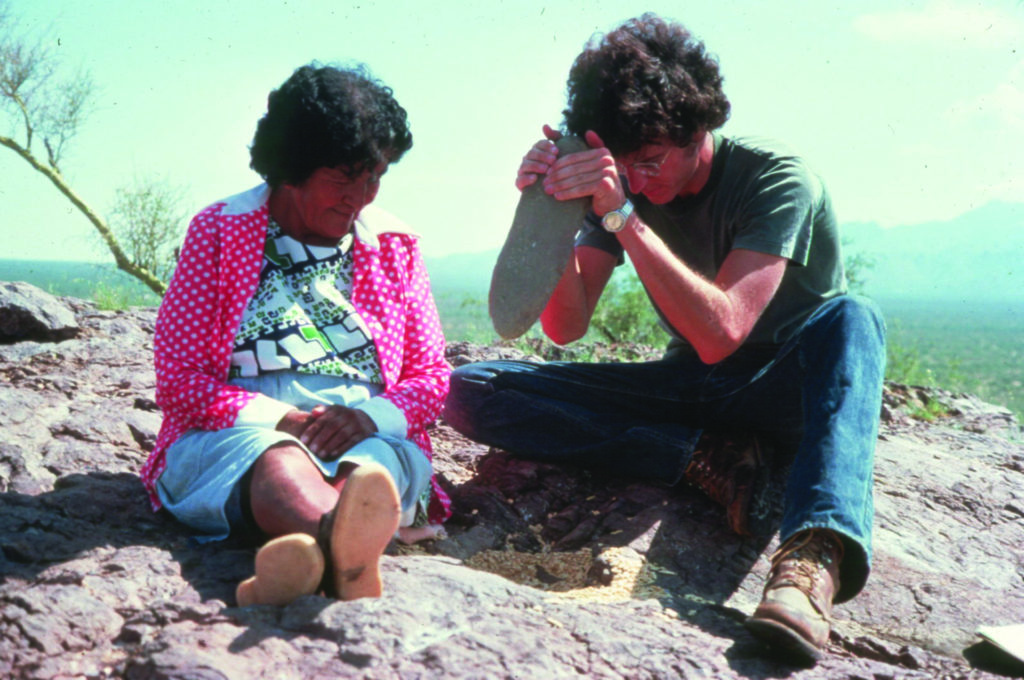

Ethnographic studies from the southern Southwest consistently indicate that people used mortars to process mesquite. This commonly took place near one’s residence, and the mortars and pestles were of hardwood or stone. Of course, wooden implements do not preserve well, and few have ever been found in archaeological contexts. On the other hand, archaeologists generally find bedrock mortars in the landscape peripheral to villages and other residential settings. I’ve long wondered why so much mesquite processing took place away from the comforts of home, and while I’m still pondering that question, I have some ideas.

I often find bedrock mortars in association with petroglyphs, sometimes very dense concentrations of them. This suggests to me that sometimes, people embedded mesquite-pod collecting and processing into a holistic use of the landscape, and that it was probably a major seasonal tradition—as we know it was in the ethnographic past—involving rituals, songs, and stories. Another reason may be that some mortars predate settled agriculture life in the Greater Southwest, and therefore have nothing to do with nearby villages. In that case, they would be associated with strategically situated camps of more mobile Archaic hunter-gatherer communities. This would also apply to hunter-gatherer communities whose territorial ranges overlapped with those of contemporary or earlier agriculturalists.

Because mortars are not really grinding tools, they don’t wear out in the way metates can. People probably successively used the same bedrock mortars for many, many years—and probably people of different cultural backgrounds. For instance, some Yavapai consultants shared with ethnographer Edward Gifford that their people did not make mortars, but used the ones left by their ancestors or those of other tribes.

Another possible reason people sometimes used bedrock mortars far from their villages was to reduce the pods to a more manageable size before taking them home. The long, thin, sometimes twisted pods do not pack easily and efficiently into bags and baskets—for me, at least, they often poke through the sides and jab me in the legs and arms. When I mill mesquite pods using a hammer mill, I typically reduce a five-gallon bucket of whole pods to about 2 gallons of flour, which frees up a lot of space when one considers portability and storage. Processing pods in the field would make them more manageable, and one could gather more on any one outing.

I also often find bedrock mortars in close proximity to water sources like tinajas and springs. Again, there are probably several reasons why this is. A water supply would be desirable for anyone engaged in fairly rigorous labor, such as pulverizing pounds and pounds of mesquite pods in a mortar. Such places tend to have a bit more vegetation around them on account of the water, which provides more shade, as well as more mesquite pods. Also, water is needed when processing mesquite for eating and storing, so perhaps people used the bedrock mortars for immediate consumption of the mesquite pods or they prepared “mesquite turtles” in the field for transport and storage back at their villages.

Another curious aspect of bedrock mortars is that I often find them in groups, rather than as solitary features. If mortars could be used routinely without wearing out, then why do we tend to find them in clusters? I suggest this tells us something about the social nature of mesquite pod collecting and processing. Most ethnographic accounts share that these were group activities, and groups of people would certainly need more than one mortar to efficiently process their pods. Even more, most of these groups were made up of women who were responsible for collecting and processing the mesquite pods and then using them to feed their families. Does this mean many of the petroglyphs scattered around bedrock mortars owe to female minds and hands? Perhaps.

Sometimes bedrock mortars are placed so close together that it would be impossible for them to be used at the same time. I’ve encountered this at the Bouse Site, where 48 mortars literally cover the surface of a bedrock outcrop with little to no room between them. All mortars are still functional, but only a few could have been used at any one time. So why so many in one place?

Don Laylander, an archaeologist who works predominantly in southern California and northern Baja, has suggested that such contexts may inform on concepts of ownership and personal property. Perhaps mortar holes were owned by individuals or families, in which case it would be socially improper to use another’s without permission. Alternatively, perhaps people avoided others’ mortar holes. Laylander noted that taboos against reusing property of the deceased were widespread among southern California tribes, and we can extend that further to include Yuman and O’odham communities in southern Arizona. At the end of the day, though, I still find myself scratching my head about the possibilities and complexities surrounding these holes in the ground.

Quechan and Piipaash communities also used a portable type of mortar that we will probably never find in archaeological contexts. These mortars were actually textiles created by weaving together arrowweed twigs and split roots. People placed these in shallow holes in the ground and proceeded to pulverize mesquite pods with stone or wooden pestles. They collected the resulting flour by careful removing the woven mat of twigs and roots from the hole.

Any consideration of the archaeology of mesquite would be remiss without a nod to the gyratory crusher. This is one of the most peculiar ground stone items I know of, and in my 20 years of fieldwork I’ve never found one. Gyratory crushers look like portable stone mortars but with a hole in bottom. People generally credit legendary archaeologist Julian Hayden with identifying these devices and explaining their operation, but it was actually his brother who recognized their likeness to cone crushers used for reducing rock into gravel and sand.

Observing that the holes in the bottom of the “mortar” exhibit polishing on both upper and under sides and along their circumference, Hayden inferred that the hole (technically a frustum) was part of the tool’s design and not a result of wearing through the base or intentionally “killing” it. He surmised that people used a long wooden pestle with a nipple at its tip. The nipple fit in the hole and blocked mesquite pods from falling through. By gyrating the pestle in a circular motion with the nipple set in place, one could grind mesquite pods quickly and efficiently: the flour would fall through the divots between the pestle’s nipple and the frustum and collect below.

Oddly, gyratory crushers never gained wide acceptance in the Southwest despite the ubiquity of mesquite and practically every community’s reliance on it. Hayden found them in the Sierra Pinacate of the Gran Desierto del Altar in the northwest corner of Sonora, Mexico, and learned of others from Texas and the western Sierra Madre in Mexico, but the intervening areas were utterly devoid of them. To this day, no one has followed up on Hayden’s study (published in 1970) to determine whether gyratory crushers have since been found or identified in other places of the Greater Southwest.

Until then, we at Archaeology Southwest will be experimenting with a gyratory crusher made by ancient technologies expert Allen Denoyer. Allen just finished it, and the timing is perfect, because the mesquite pods will be ripening in just a matter of days. The crusher is of basalt and the pestle is of mesquite wood. Give us a few weeks to test it out, and we’ll let you know how it worked.

3 thoughts on “A Brief Cultural History of Mesquite”

Comments are closed.

i adopted a burro from the b.l.m. wild horse & burro program. part of her diet has been “pechitas” (mesquite beans). also, i find a lot of wild animal scat while hiking, some of which has mesquite seeds as a source for their diet. i would be interested in knowing if native cultures in the southwest have utilized “pechitas” as part of their domesticated animals diet? this of course would be domesticated animals introduced by the spanish and other old world cultures?

Absolutely they did/do, for cattle and beasts of burden. If you read early explorer journals, they are full of references to how much the cattle and horses loved to eat mesquite pods.

What’s the earlirst known date for the presence of mesquite in the Mojave Desert?