- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- The Legacy of Marshall Sahlins…Southwestern ...

(April 13, 2021)—Marshall Sahlins (1930–2021) passed on Monday, April 5. Sahlins was a giant in cultural anthropology, and his caliber and influence cannot be overstated. He was prolific: his seminal works, from Stone Age Economics (1971) to On Kings (2017) with David Graeber, stand alongside two dozen other books and more than 150 articles examining culture theory around the world and through time.

Although these contributions are well documented, those showing Sahlins as an archaeologist are less well known—even to himself!

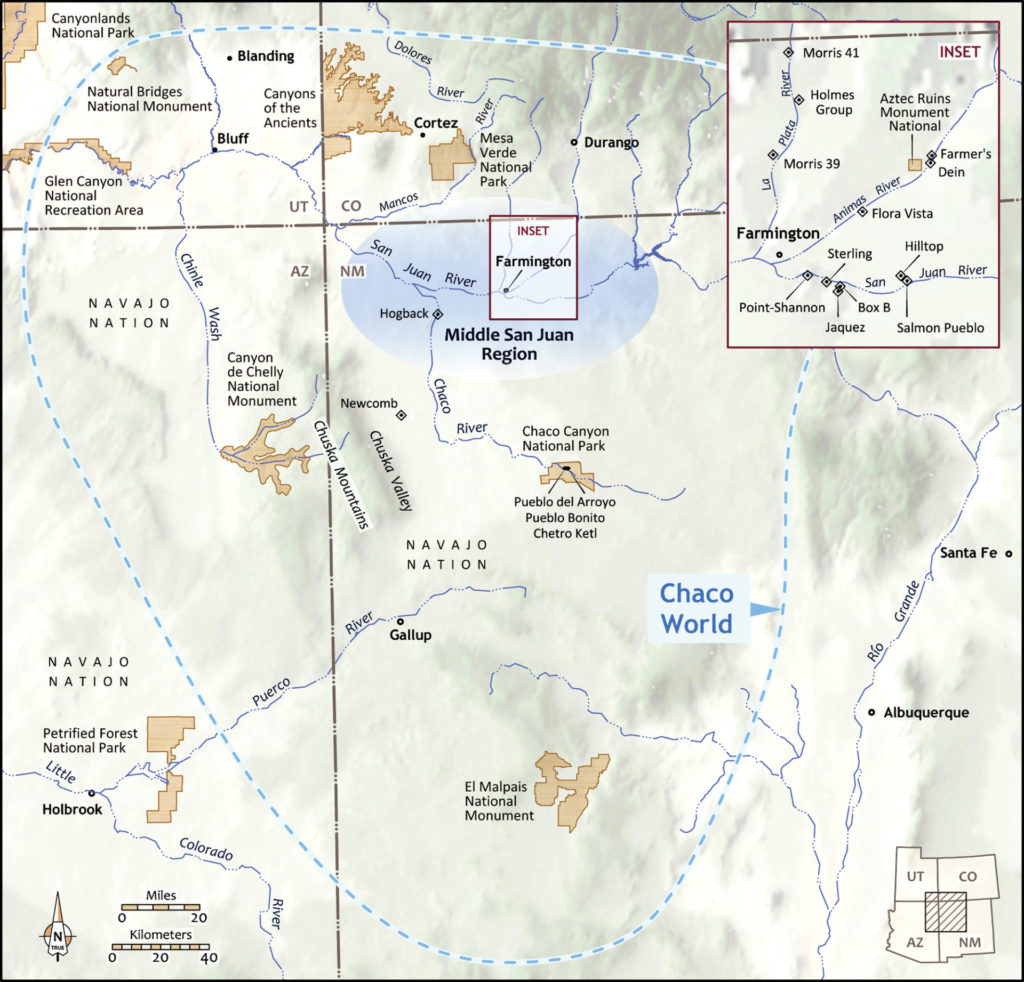

Before his luminous career even started, the young graduate student from Columbia University and his new bride set off in a ramshackle car for an extended vacation in the US Southwest. Bumping along new roads plowed by oil and gas prospectors, the couple somehow found themselves, quite literally, on the wrong side of the San Juan River southeast of Farmington, New Mexico. They were on the farm of a Mr. Roberts in an area archaeologists hadn’t yet broached.

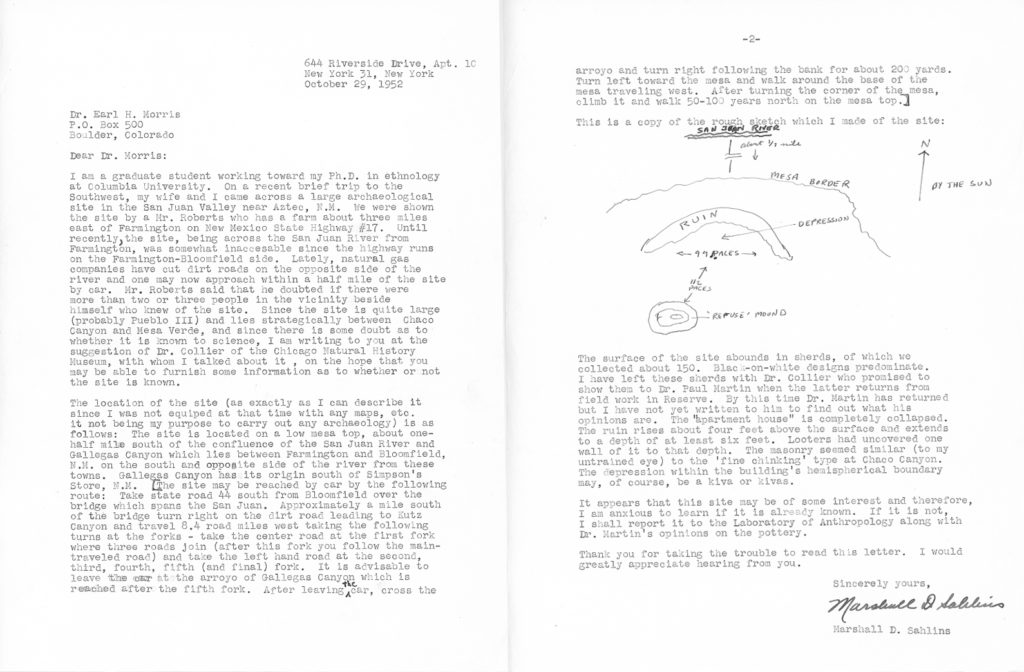

Sahlins hadn’t intended to undertake archaeology, but the collapsed masonry, scatter of thousands of sherds, and deep midden depression beckoned from a cliffside above an arroyo. Marshall explored, observed, paced, drew, and collected, ultimately creating a detailed map of a Chacoan great house that had not yet been recorded by professional archaeologists.

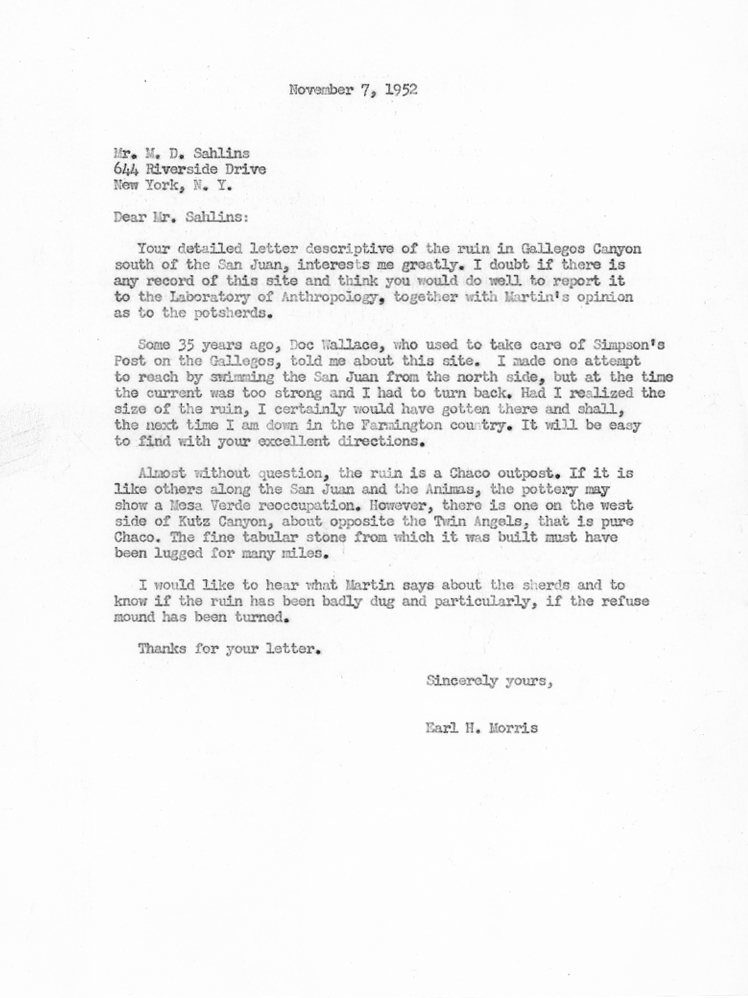

The Sahlinses eventually returned to their tiny apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, just off Riverside Drive and a few blocks from Alexander Hamilton’s Grange. Marshall typed a two-page letter to renowned archaeologist Earl Morris in Boulder, Colorado. Morris was a Columbia alumnus with strong ties to San Juan Basin archaeology.

Earl immediately wrote back; he was impressed by the data and longed to visit the site. Despite decades of work in the region, he’d never been there, though he’d heard of its existence decades before. The remoteness, the farmer’s reluctance, and the river’s current prevented his visit.

Thus, Marshall Sahlins became the first person to record the site we now call Jaquez (LA 2609), a 900-year-old, ~125-room Chacoan outlier just south of the San Juan. The site was later recorded by Cynthia Irwin-Williams, who excavated a few test units there. Archaeology Southwest’s own Paul Reed has examined the site and written about it (see, for example, Archaeology Southwest Magazine vol. 28, No. 1).

Sixty-two years later, in 2014, I stumbled across the Morris–Sahlins exchange in the archives of the University of Colorado’s Museum of Natural History. Although it was outside my research interests, I couldn’t pass up this bit of living history.

I emailed Dr. Sahlins. The then-82-year-old responded—within about 15 minutes, at midnight, via his iPad—that he remembered the discovery quite well, though he couldn’t remember what had happened to the 150 sherds he collected once he’d sent them to Paul Martin at the Field Museum. He then went on to joke: “I am impressed by my youthful archaeological knowledge and ability to describe the space—both of which capacities I lost long ago. Perhaps I missed my calling,” (emphasis added; Sahlins, personal communication 2014).

We had a pleasant exchange, and he was tickled that I’d given him credit for first recording the site in a presentation I made at the Pecos Conference. (I also made sure he was properly credited in the Chaco Research Archive.)

Marshall Sahlins, Southwestern Archaeologist. Wouldn’t that have been interesting!?

2 thoughts on “The Legacy of Marshall Sahlins…Southwestern Archaeologist?”

Comments are closed.

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.

Cool tidbit Erin. Great use of archival documents!

I took graduate anthropology courses with Mr. Sahlins at the University of Chicago 30 years ago. He was a formidable intellectual and an inspiring teacher. I think he appreciated the appeal of archaeology as a subject matter, but he was disdainful of most archaeologists (I was and am one), whom he saw as lost in a simplistic materialism. Archaeologists today (or any social scientist, of any age or theoretical bent) would benefit from close readings of his work, especially his later work, beginning with his classic book, Culture and Practical Reason.