- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- On Conferencing & Indigenous Data Sovereignty

(September 5, 2024)—In this post, we offer some individual reflections on our participation in several professional conferences in 2024.

Skylar

I had the privilege of attending three professional conferences—two here in Tucson and one in New Orleans, Louisiana. The Tucson conferences were “Confluence,” hosted by the Center for Collaborative Conservation (April 2–4), and the inaugural “U.S. Indigenous Data Sovereignty & Governance Summit,” hosted by the U.S. Indigenous Data Sovereignty Network (April 11–12). I also attended the 89th Society for American Archaeology Annual Meeting (April 17–21) in New Orleans, Louisiana, for the first time.

Confluence

I’ll start with Confluence. This conference was all about conservation, and more specifically collaborative conservation initiatives happening across the western part of the nation. As my position title indicates, most of my work for Archaeology Southwest revolves around collaboration, advocacy, and our conservation initiatives, so I felt most at home at this conference. Indeed, I was invited to this conference by a fellow Diné woman who was a part of its planning committee to present the Tribal Collaboration Model to the other conservation organizations present, many of whom are engaging Tribal Nations or supporting Indigenous-led conservation projects.

It was heartening to see that the conservation world is realizing they can no longer exclude Indigenous Peoples from the work happening to protect their ancestral homelands. I was also happy to play a small part in that by making organizations and people aware of the model and how we are applying it to our work here at Archaeology Southwest. Another notion I took away from this conference was that Archaeology Southwest is not well known, or known at all really, as a conservation and preservation organization among the small world of conservation nonprofits. I hope that we can have a larger presence at events and conferences like Confluence going forward.

Society for American Archaeology Annual Meeting

On the total other end of the spectrum, in terms of feeling at home, the SAA’s Annual Meeting had me feeling totally out of my depth. I am not an archaeologist, but I do hang out with them a lot, so I was a bit surprised by that feeling. (I had just come from a two-day fly-in to Washington DC to advocate for the protection of the Great Bend of the Gila as a National Monument, so maybe I just didn’t have the time to be nervous.) Although Confluence was a fairly large event, the SAAs are massive. When I registered and was handed the program for the conference, I wasn’t expecting it to be a literal book about an inch thick! Talk about overwhelming. But in my usual way, I decided to just go with the flow and not have any preconceived notions.

I don’t know the exact number of registrants, but it is in the thousands. It is large enough that although there were many other Archaeology Southwest staff in attendance, I didn’t run into any other than the few who were in the same sessions I spoke at or attended. In that session, again, the Tribal Collaboration Model made an appearance, but this time more in the context of how Archaeology Southwest is evolving as we aim for our goals of collaborating with Tribal Nations, Indigenous Communities, and Peoples.

After presenting and supporting fellow Staff during their sessions, I wandered and mingled. I happened to come across a table with people recruiting for the “Rock Art Interest Group”. This caught my attention, as much of my fieldwork with our Lower Gila River Ethnographic and Archaeological Project (LGREAP) has been documenting petroglyph sites. An interesting debate sparked up in the interest group regarding the use of the term “rock art” in reference to petroglyphs and pictographs put down by Indigenous Peoples. I was the only Indigenous person present, so inevitably everyone looked at me and asked, “What do you think?”

I related that although the term “rock art” isn’t necessarily offensive, it also doesn’t capture the depth of what petroglyph and pictograph panels encapsulate. I also related that this term’s usage is a symptom of a greater problem in archaeology in general—the absence and exclusion of Indigenous Peoples. I also emphasized that if these types of decisions continue to be made without Indigenous Peoples in the room and at the table, then in 50 years this debate is going to repeat when practitioners land on another term that is problematic in the way “rock art” is today. I was met with silence. I’m mostly a quiet person, so it didn’t bother me, and I hoped it meant they were taking to heart what I had related.

U.S. Indigenous Data Sovereignty & Governance Summit

From the University of Arizona’s Native Nations Institute: Indigenous data sovereignty is the right of a nation to govern the collection, ownership, and application of its own data. It derives from tribes’ inherent right to govern their peoples, lands, and resources. (https://nni.arizona.edu/our-work/research-policy-analysis/indigenous-data-sovereignty-governance)

“Data are not a foreign concept in the Indigenous world. Indigenous peoples have always been data creators, data users, and data stewards. Data were and are embedded in Indigenous instructional practices and cultural principles.” — Stephanie Carroll Russo, Associate Director, Native Nations Institute

This summit gave me mixed feelings of being at home and out my depth all at once. I felt at home because the vast majority of participants were Indigenous people from various Tribes all across the nation, as well as from Aotearoa (New Zealand) and the First Nations of Australia. The Summit started with a shared meal followed by an offering of sage, a blessing, an acknowledgement of the four cardinal directions, and a prayer. Smelling that sage fill the room immediately grounded me and brought up memories of home in Dinétah. Taking the time to do this is something that sets apart Indigenous events and gatherings from other conferences. Then, the programming started and I found myself feeling like a freshman in a 101 class again.

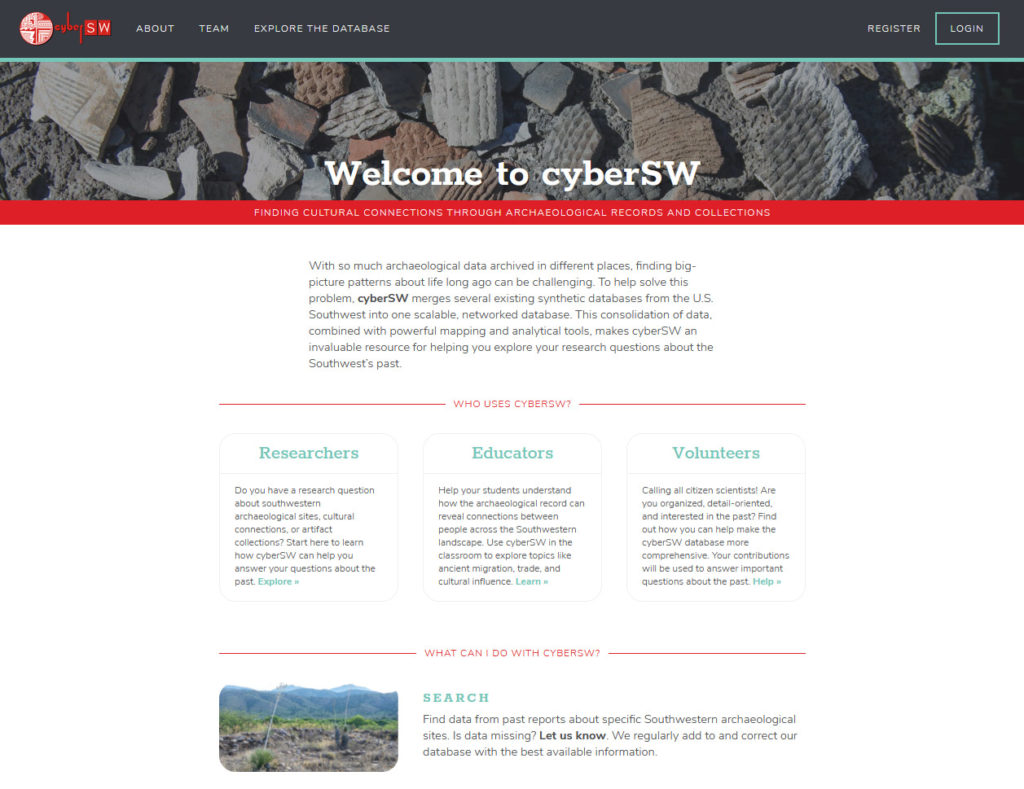

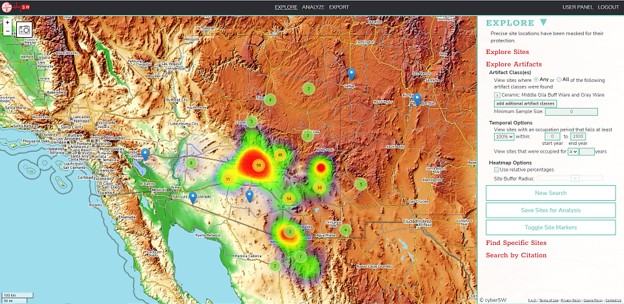

Data sovereignty and governance is not something I am very familiar with, and this is the main reason I hoped to attend the summit alongside other staff and members of the cybersw Tribal Working Group who participated virtually. Because cyberSW is a database, and because Archaeology Southwest and archaeology in general deals with Indigenous data and knowledge or that derived by the study of Indigenous People’s material legacies, it seems paramount that we begin to contemplate how our organization can uphold Indigenous data sovereignty. For the most part, sessions focused on Indigenous Data Sovereignty in the worlds of public health, Tribal governance, census, and environment. There was one session about how data sovereignty can be applied in a conservation context, but there wasn’t one in regards to archaeology or anthropology—although there was some discussion about the Native American Graves and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). I have come across some literature about data sovereignty in regards to archaeology, but there isn’t a whole lot. This drives home the fact that this is new territory not only for Archaeology Southwest, but also (hopefully) archaeology as whole.

After a month of travel, conferencing, advocating, and just people-ing, my social battery was drained. As I write this over the summer, I am glad to have had some down time and some alone time to reflect on these travels and learning journeys.

Caitlynn

More than 400 Indigenous peoples and allies attended the first U.S. Indigenous Data Sovereignty & Governance Summit held on the land of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe and the homelands of the Tohono O’odham. Archaeology Southwest team members Skylar Begay, Joshua Watts, myself, and our former Tribal Director of Tribal Collaboration in Research & Education, Ashleigh Thompson, attended the summit in person. At the same time, some of our cyberSW Tribal Working Group members joined us virtually. Over the course of two days, the ASW team attended a wealth of workshops and roundtable discussions on how to demystify and protect Indigenous Data.

Data is not reserved for measurements and findings documented in the printed reports and journals of scholars. Data is also the collection of knowledge from experiments and observations to be shared within a community. Data has been intrinsic to Indigenous culture. Indigenous People’s stories, artwork, tools, ceremonies, and other practices are data— this, in turn, makes Indigenous Peoples data stewards. Indigenous data is now more often referred to as Indigenous Knowledge, yet the value of this knowledge should not be immediately discredited as a fable, and research protocols involved in obtaining Indigenous data should be reframed to ensure data justice and equity.

Indigenous Peoples have become inured to the injustice of data exploitation and misinterpretation by Western scholars. Indigenous data has been siloed from most research fields through terms such as “primitive” or “folklore.” Despite being dismissed by scholarly research, Indigenous Peoples are still fighting for the right to manage their data. Indigenous data is critical to the work of cyberSW because the archaeological information about the Southwest found in our database is, fundamentally, Indigenous data.

Throughout the Summit, a recurring question was posed: How should institutions improve their approach when working with Indigenous communities and their data? This topic has been explored and best expressed by the late Vine Deloria Jr. in Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto, in which he asserts that a closer look should be taken at those who study humanity, and by extension Indigenous Peoples, to determine if they’re more concerned with license or freedom (Deloria, 1969, p. 95). Indigenous Peoples, communities, and Nations deserve the same respect as partners—not as research subjects. This calls for the researcher to ask serious questions of their work when the project involves Indigenous Peoples or heritage places. Questions such as, but never limited to: Is this research helpful? Who is my intended audience, and what will I do with the knowledge shared? Does the community want this research project? Am I willing to adapt my project to meet the community’s needs? How will the data be managed? Will the project provide transparency and opportunity for ongoing consent?

When addressing institutions that have been established through researching, interpreting, and documenting heritage materials and places, it is crucial that such organizations not only recognize their responsibility, but also actively honor and respect ancestral landscapes and the knowledge that lives within the land. Research involving Indigenous places and people should be developed within the community to meet the community’s needs. When engaged in a research project as an outsider, the role should be collaborative and mutual—sharing tools and expertise where appropriate and not overburdening the whole of the work on Indigenous Peoples. There must also be a call to institutions and organizations that work with Indigenous data and archives to ensure that their operation acknowledges the historical injustice of collecting Indigenous ancestry and that their organization is taking conscious actions to reduce harm.

A final reflection: While attending the Summit, our team observed that we might have been the only archaeology organization present. Although that is a bit discouraging, we chose to view our presence as a positive—as a sign that we, as an organization, are actively listening and willing to support Indigenous scholars and sovereignty.

Resources and projects from the U.S. Indigenous Data Sovereignty & Governance Summit

The First Nations principles of OCAP (Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession)—Principles of Indigenous Data Sovereignty developed by the First Nations Information Governance Centre.

- First Nations Data Governance Strategy (2020)—an executive report for First Nations-led data governance.

The Rematriation Project—Inuit-led and Inuit-serving digital database in partnership with students from Virginia Tech.

- Carroll, Stephanie Russo; Garba, Ibrahim; Plevel, Rebecca; Small-Rodriguez, Desi; Hiratsuka, Vanessa Y.; Hudson, Maui; and Garrison, Nanibaa’ A. Using Indigenous Standards to Implement the CARE Principles: Setting Expectations through Tribal Research Codes. Frontiers in Genetics Vol. 13. 2022. DOI=10.3389/fgene.2022.823309. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fgene.2022.823309.

Protocols for Native American Archival Material (NAU)—best practices for care and use of Indigenous archival materials.

Community-Driven Archives Initiative (ASU)—an award-winning initiative to address power imbalances of archives.

Joshua Watts, cyberSW Manager

In April I joined colleagues from Archaeology Southwest (ASW) to attend a conference near Tucson on Indigenous data sovereignty (IDSov). I went into this conference without much of a personal agenda… I mean, I work in archaeological data management on the cyberSW project and spend much of my time facilitating archaeological research, so there was clearly some need to engage on this topic and start figuring out where our work intersects with IDSov. But my only plan was to listen. This post represents my first attempt at processing some of what I heard, and how it has helped me start to make sense of some of my struggles thinking about the ethics of data preservation and reuse, as well as Preservation Archaeology, all in the context of a very real commitment to Tribal collaboration at ASW. I suppose this is a self-therapy download of sorts!

I cannot possibly be the first to articulate this, but one of the key epiphanies for me was a shift in emphasis toward process over products in the context of Tribal collaboration. I think it’s finally dawning on me that although research products and results remain relevant (published papers, professional presentations, grants, etc.), it’s also important to acknowledge that engaging in the collaboration process and relationship-building is a hugely important outcome itself. One that is almost, but not actually, independent of the research products.

Interestingly, I have tended to be able to embrace this approach in much of my life—particularly my hobbies—but I find it awfully difficult to translate to my job. At work it’s usually “get the damn paper published,” or the grant proposal submitted (or the database uploaded, etc.). When the milestones are mostly products, it is important to allocate effort to get the work done on those products efficiently, but—at least in my job—the effort is rarely closely examined or rewarded itself. So how do you let go of the product, just a little at least, in favor of embracing the process?

Here’s where the self-therapy part of the essay kicks in, and this is perhaps highly specific to my hobbies. I ask you to consider the analogy of training for a bike race or marathon: Sure, the goal of getting podium results in a race is fine… but it’s risky. If you can frame the race as penciling an event on the calendar to focus your training AND you learn to enjoy the process of training… you’ll put in the work and more likely have a better outcome. Race results are the product and training is the process; focus on the latter and the former will benefit. And even if you whiff it at the race… worst-case scenario is you got fitter/stronger/healthier for having committed to the process. (Don’t get me wrong, I’d rather embrace the process and be relevant in the race… but truth be told you have way more control over the first part than the second).

People who focus on process are coachable, failure is a thing that happens, and you adjust accordingly. You push yourself, sometimes too far. But it’s part of the process. Reset, keep trying, get better. A focus primarily on product only makes failure incredibly expensive and frankly soul crushing (if failure isn’t a thing that often happens to you).

Pivoting back to the IDSov conference: One afternoon I found myself trying to explain to an older (white) researcher, a biologist, that a lot of our attention at cyberSW (and ASW more broadly) has been on the process of Tribal collaboration, perhaps (or often) at the expense of some efficiency in generating research products. Building relationships, developing agreements, engaging Tribes and individuals, figuring out ways that any products we generate will be—at least on some level—legitimately valuable to Tribes. And also trying to explain that he’s well positioned to initiate a process but that the product he’s focused on (e.g., saving endangered species) might not be a thing he solves with Tribes on any kind of timeline he’s used to working with. Basically, I was starting to make the same case I’m making here: The process is a worthy goal in itself. Give yourself some credit accordingly.

And to be clear… engaging in the process of collaboration is going to look very different depending on context and capacity and topic. I don’t believe every single research product in Southwestern archaeology needs to be owned by or controlled by Indigenous peoples; there are things they’re not particularly interested in but archaeologists will almost always swear by (e.g., pottery counts by ware and type?!). But on most topics of interest to ASW and its membership, I think it’s essential (and reasonable) to engage Indigenous advisors in an ongoing, regular process for ideas and feedback. The extent that the final products get shaped by the collaboration process will, understandably, vary.

Fundamentally, I am a data scientist and a social scientist who works with archaeological datasets. The overlap with IDSov concerns is hard to ignore: While our data were for the most part created by white/colonial researchers and compliance specialists, they pertain to the ancestors of Indigenous Peoples, and management of those datasets is clearly relevant to their heritage.

But, because things are never simple, I remain committed to broadly relevant synthetic archaeological research. That’s a bit of a different mission than being wholly focused on righting the wrongs of past/present practitioners in archaeology (and is occasionally out of alignment with ASW itself). The ethic that underlies a lot of my work on data is encapsulated by the FAIR Principles—data should be Findable; Accessible; Interoperable; Reusable. ASW’s development of cyberSW has tried to realize these themes since before I came to work on the project. But sometimes the ethics of open data bump up against engaging ethically with the descendants of the people whose data I’ve helped aggregate into cyberSW.

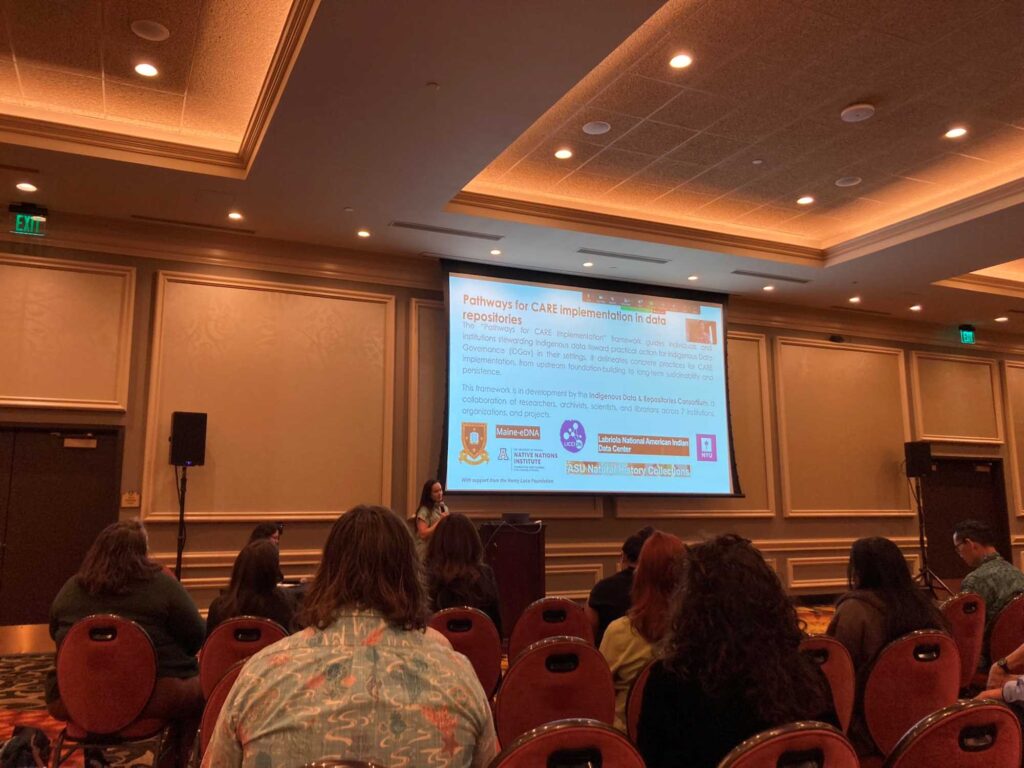

Although I had encountered the CARE Principles (for Indigenous people, there should be Collective Benefit; Authority to Control; Responsibility; Ethics) before the IDSov conference in April, that meeting forced some reflection on where I want to position myself regarding that more advocacy-adjacent role for data. I’ll continue learning and evolving. I’m acknowledging that while it sure helps to have done some thinking about data management in this context, fundamentally most of it is really not up to me. Instead, it’s clearer that if we’re going to work in this space, we need to step up and engage in the process of consulting with and collaborating with Indigenous people and communities on data issues, insofar as they are interested and able. And, perhaps, try to suck at collaboration a little less and maybe even get sorta good at it.