John R. Welch

Director, Landscape & Site Preservation Program

Skylar Begay, Diné, Mandan and Hidatsa

Director, Tribal Collaboration in Outreach & Advocacy

Ashleigh Thompson, Red Lake Ojibwe

Director, Tribal Collaboration in Research & Education

Paul F. Reed

New Mexico State Director, Preservation Archaeologist

What Is TCM?

At the broadest level, Tribal Co-Management (TCM) means principled collaborations among holders of rights and responsibilities to reach and implement decisions affecting matters important to Tribes. TCM can address belongings or information in the custody of government or private entities.

Alternatively, as discussed here, TCM can focus on Territory (also known as Ancestral Lands), meaning lands and waters intrinsic to the sovereignties of the Indigenous Peoples of the United States (U.S.) but beyond their U.S.-designated Tribal Trust Lands, or “reservations.” Territory-centered TCM has become prominent in public lands management, especially in the contexts of the decade-long effort to protect Bears Ears National Monument and recent campaigns by multiple Tribes to secure co-stewardship agreements in order to assist the U.S. Forest Service and other agencies in caring for their Territories and associated places, values, and belongings.

This contribution to TCM dialogues seeks to inspire discussions of TCM and to enable TCM for the proposed Great Bend of the Gila National Monument, if the affected Tribes are interested in doing so. As staff members at the nonprofit Archaeology Southwest, our goal is to advance the organization’s overall mission and our commitment to building relationships with Indigenous Nations, communities, and Peoples.

To these ends, we offer a basic rationale, grounded in legal and moral principles, for pursuing TCM in conjunction with Tribes’ political and cultural representatives. We then review “ingredients” for TCM, summarize some existing TCM arrangements (mostly in the U.S. Southwest), and identify some impediments to successful TCM. By successful TCM, we mean co-management that involves shared decision making among the parties, as well as mutual and proliferating benefits to the affected people and Territory.

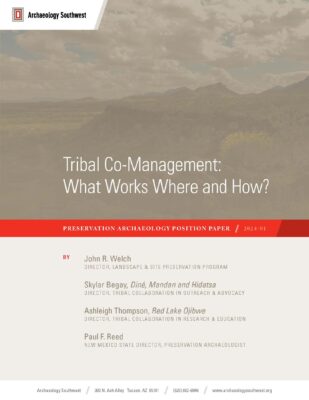

Most public attention to TCM has focused on Tribes’ campaigns to protect and to participate in decisions affecting Tribal treaties and sacred sites. Away from media spotlights, representatives of Tribes and government agencies have been working for decades to craft alliances between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples to take care of land, water, one another, and other-than-human lives and communities. Lessons learned from co-management efforts in the U.S. and elsewhere show that TCM can be configured to advance the interests of one or more Tribes in any area of Territory and in collaboration with almost any number or type of duty- or stakeholders (that is, federal, state, and local governments, as well as private and community entities). In this sense, TCM occupies a substantial portion of a spectrum that ranges from centralized government decision-making to dispersed, community- or user-based rights and duties (Figure 1). The brightest and most defining line in the spectrum is that separating co-stewardship, in which Tribes remain advisors, from co-management, which involves assertions by Tribes of rights to make decisions regarding their Territories.

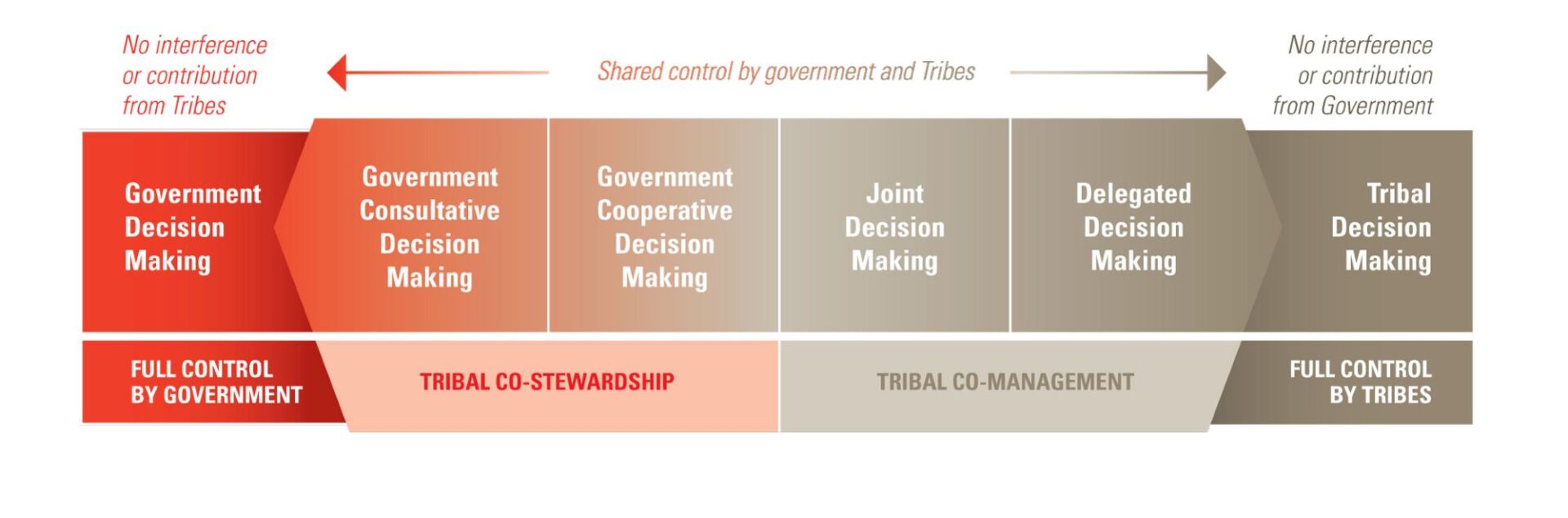

TCM structures and processes are diverse. Most successful TCM arrangements are tailored to accommodate key attributes of a Territory and to optimize concordances among Tribal and government agency values, interests, and preferences. At the same time, all or most TCM arrangements share the four essential attributes depicted in Figure 2. TCM “rooting” and thriving are conditioned upon specifications concerning where TCM is authorized, who is responsible for oversight and implementation, how commitments are made, and what success looks like in the short run and in the mutually desired future.

Why TCM?

TCM is one tool for addressing fundamental problems—moral, legal, political, and practical—stemming from the truth that 100 percent of the U.S. comprises Indigenous Territories, mostly taken without due process, fair compensation, or the takers’ foreknowledge of pre-existing, often intricately coupled, social-ecological systems. Tribal Trust Lands reserved from non-Indigenous use make up about only about 2.3 percent of the U.S. Until Landback becomes widespread, TCM provides a tool to reclaim and regenerate Indigenous–Territory relationships and to otherwise unfence land stewardship.

Tribal officials may be reassured to learn that TCM is definitely not intended to give outsiders any authority over Tribal Trust Lands. A growing number of government officials are finding that their agencies benefit from increased financial and technical assistance in land stewardship and management activities through collaboration with communities who have stewarded their Territories since time immemorial. Non-Indigenous private landowners may elect to follow Archaeology Southwest and other stewards of land preserves by welcoming TCM, but are under no legal obligation to do so. As of 2024, participation in TCM is voluntary except where backed by legislation (for example, the El Malpais Conservation Area, discussed below).

Two further truths offer practical guidance in pursuing TCM.

- Collaboration matters. Indigenous Peoples have, through relationships built across millennia with Territories and their constituents—especially plants, animals, waters, soils, and fire—created innumerable stable, diverse, and productive ecosystems.

- Knowledge matters. Indigenous ways of environmental understanding and caretaking offer clear guidance for shielding communities from the worst effects of climate change, diminishing biodiversity, and desertification. Much of this Indigenous knowledge (IK) (also, traditional ecological knowledge [TEK]) applies primarily to specific eco-cultural contexts; however, Indigenous ways of valuing, learning, balancing, and collaborating offer lessons for engaging Tribal communities, organizations, and knowledge holders to rediscover pathways to sustainability, resilience, and conciliation.

The bottom-line argument for advancing TCM is this: Lands and waters deprived of relationships with human stewards need and deserve opportunities to resume and refresh relationships that cross cultural, organizational, and jurisdictional boundaries; human communities in general and Tribes in particular thrive through relationships with Territory and one another.

What Helps TCM Succeed?

Although the U.S. has seized control over many Indigenous Peoples’ Territories and facilitated historical and ongoing harmful and industrial uses of those lands and waters, Indigenous Peoples maintain diverse rights to their Territories. Indigenous Peoples also retain distinct, often deeply engrained responsibilities and capacities to reclaim relationships to these lands and waters and to demonstrate how to care for Territory so Territory can guide and care for all life, all relationships.

Tribes’ rights, responsibilities, and IK have inspired public officials and private stewards to solicit Tribes’ help in learning, knowing, and acting in relation to Tribal Territories and specific places. Since the 1980s, the Pueblos of Acoma and Zuni and the Ramah Navajo Community have advised the U.S. National Park Service and Bureau of Land Management (USBLM) on the care and interpretation of El Malpais National Monument and National Conservation Area. As authorized by Congress in 1987, this TCM arrangement recognizes the affected Tribes’ long-standing values and authorizes limited vehicular access to wilderness areas for cultural purposes. Also in New Mexico, the 2001 proclamation that designated Kasha-Katuwe National Monument requires USBLM to care for the lands in close cooperation with the Pueblo de Cochiti, to pursue ecological restoration focused on places and species important in Cochiti culture, and to discourage visitor use of sensitive areas identified by Tribes’ representatives.

A 2020 report builds on prior experience with TCM and provides a “road map” to TCM success. Bridges to a New Era, by Monte Mills and Martin Nie, identifies TCM as a vital link between the oft-partitioned domains of Federal Indian Policy and land management policy. The report presents six TCM principles to guide new types and levels of involvement by Tribes in managing Territory under federal government control. The six principles emphasize government actions:

- Recognition of Tribes as sovereign governments

- Incorporation of the federal government’s trust responsibilities to Tribes

- Legitimation of structures for Tribal involvement in Territory management

- Meaningful integration of Tribes early and often in decision-making processes

- Recognition and incorporation of IK and other forms of Tribal expertise

- Creation of mutually agreeable dispute-resolution mechanisms

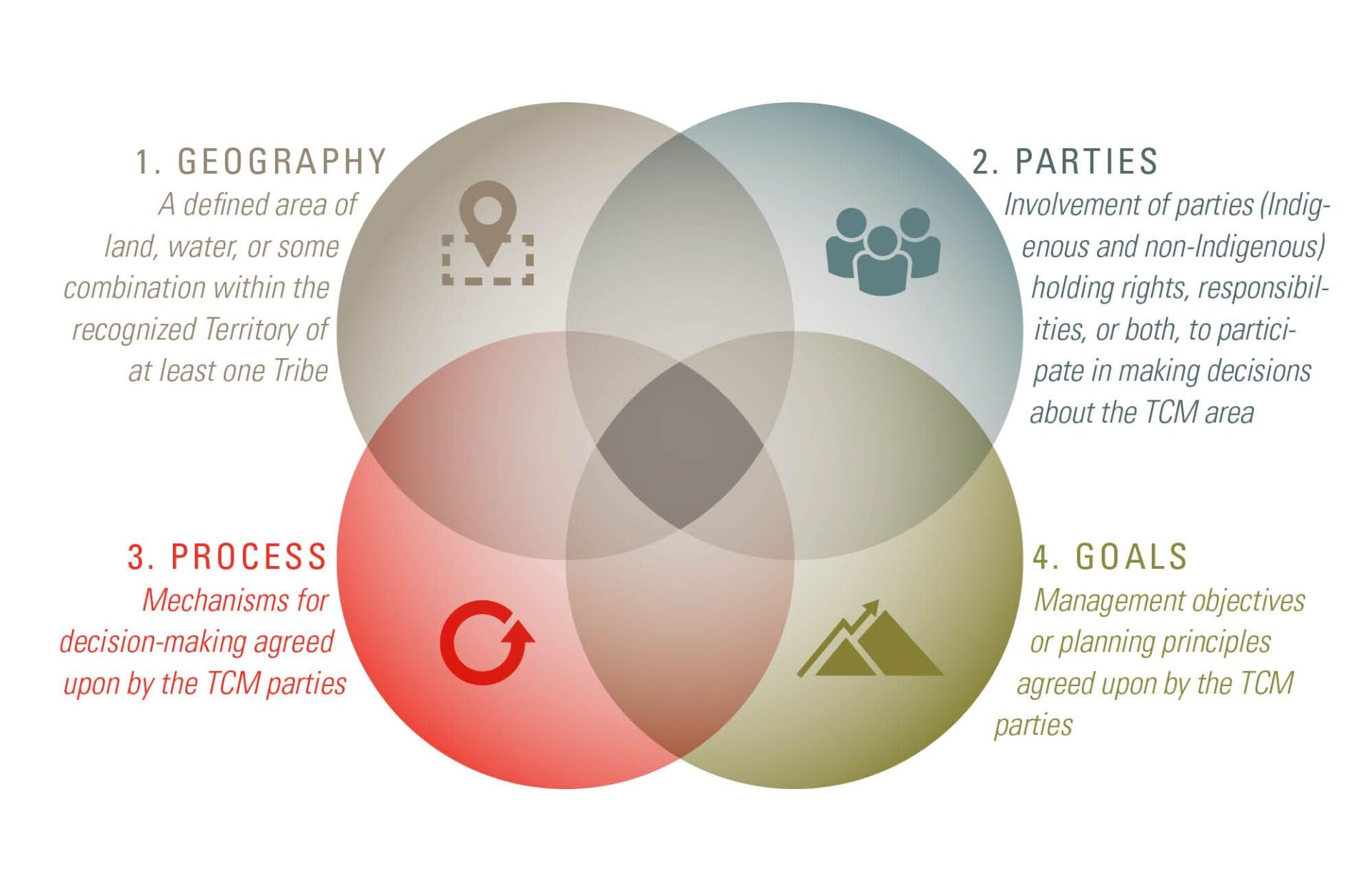

As complements to these six principles for government efforts to enable successful TCM, decades of research on factors and conditions that enable successful co-management in diverse world regions have identified six key ingredients that deserve consideration in planning and implementing TCM. Figure 3 depicts these six ingredients as sources and drivers of TCM success. We welcome and encourage use and experimentation with these conditions in crafting and assessing TCM.

Are There Problems with TCM?

At least three major stumbling blocks impede TCM success, yet each challenge also brings opportunity. First and foremost, TCM is difficult. Deliberation simply takes longer with multiple parties and diverse interests and preferences in the mix. This is especially true when, as is almost invariably the case with TCM, there are deep cultural and historical divides between parties. What does reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous nations mean when the parties have seldom, if ever, agreed on core issues such as Territory ownership, resource management, and rationales for human interventions in time-perfected ecosystems?

The flipside of these concerns is that decisions and recommendations concerning all forms of management tend to be more just and balanced when informed by diverse knowledge and perspectives. Opportunities for learning and relationship-building multiply in proportion with the range of variation in the parties’ expertise, willingness to experiment, and commitments to sharing information and other assets.

Second, some say TCM is too little, too late. Biophysical and cultural values embedded in most Indigenous Territories have been badly degraded due to extractive-consumptive use by predominantly non-Indigenous miners, loggers, fishers, and farmers. Most TCM arrangements, especially those involving state and federal government agencies, recognize Tribal officials only as advisors, not as decision makers (see co-stewardship, Figure 1, above).

Third, and perhaps most fundamentally, Western approaches to Territory management too often ignore human dependency on Earth, Sky, Wind, Fire, and other-than-human communities. Western legal and bureaucratic frameworks emphasize rights over responsibilities, short-term profits over long-term sustainability, and top-down, command-control domination over reciprocal and place-based caretaking. Done well, co-management includes invitations to build personal connections to other parties and to the Territory under management. We see rich opportunities for non-Indigenous resource managers and place-based communities to learn from and share benefits with Indigenous peoples.

How Does TCM Relate to Archaeology Southwest Programs and Actions?

Archaeology is ill-equipped to “solve” TCM’s problems. Still, as the late R&B great Robert Parker observed, “a little bit of something is better than a whole lot of nothing.” To these ends, the Archaeology Southwest Strategic Plan (2022–2024) affirms personal and organizational commitments to honor the persistent interests of Indigenous Peoples in their Territories. Our Model for Tribal Collaboration provides both full rationales for these commitments and protocols for their realization.

Specifically, Archaeology Southwest:

- Recognizes Indigenous Peoples’ cultural, property, and treaty rights in and to their Territories, regardless of present-day land ownership or management status

- Acknowledges land back as the best way to advance Indigenous sovereignty

- Encourages non-Indigenous landholders not in a position to return land to Indigenous Peoples to demonstrate trusteeship by enabling Indigenous peoples to increase involvements with and enjoy benefits from their Territories, including through TCM

- Provides preference for the employment of personnel with Indigenous identities

- Plans and implements projects and programs that foster and refine TCM arrangements in which authority and responsibility are equitably shared between Indigenous and non-Indigenous parties.

Where and How Is Archaeology Southwest Facilitating TCM?

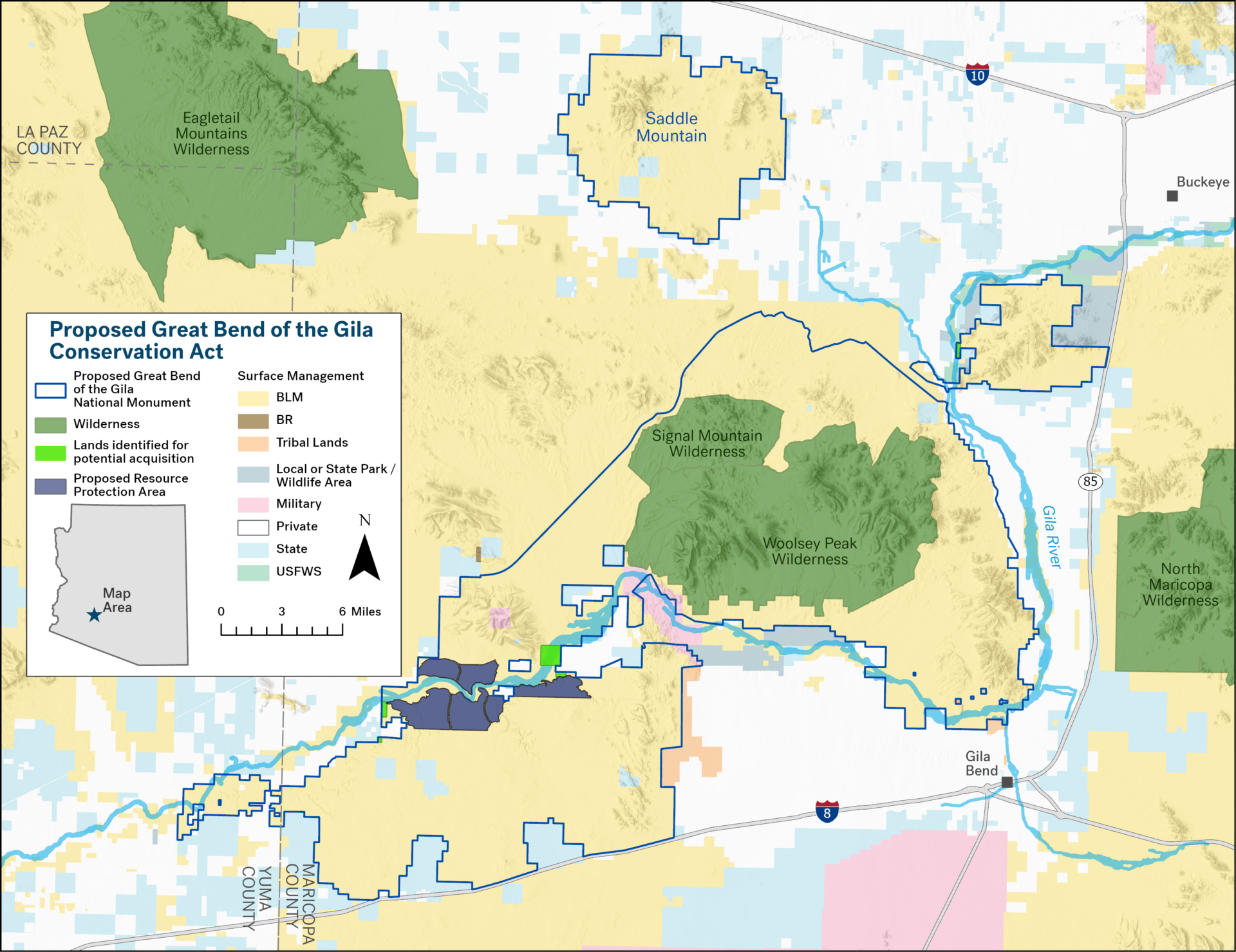

The Great Bend of the Gila National Monument, proposed for O’odham, Piipaash (Maricopa), and Tolkapaya (Western Yavapai) Territory under USBLM control in southwestern Arizona, is well suited to TCM. With the advice and consent of the 13 federally recognized Tribes associated with the Great Bend of the Gila (GBG), innumerable opportunities exist to harness the Tribes’ values, interests, knowledge, and preferences in relation to the long-term protection, rehabilitation, stewardship, and sharing of this sensitive and underappreciated riverine landscape. The GBG offers a geographical, political, and administrative venue for building Tribal capacities, enhancing relationships among the affected Tribes and USBLM, and mobilizing legal theories and proven practices to design a TCM path to desired future conditions for the Gila River, associated lands, and the human and other-than-human communities that rely on the region for material and spiritual sustenance and senses of place and belonging.

The Great Bend of the Gila National Monument being proposed for the Great Bend river corridor and nearby uplands offers a compelling context for boosting the profile and sustainability of a culturally and ecologically important area while advancing TCM policy and practice (Figure 4). This place-based initiative promises to address some nagging management problems, including overuse by off-highway vehicles, protection of sacred sites and other sensitive areas, and conciliation of Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. TCM in the GBG may also advance longer-term, system-wide innovations needed to normalize and institutionalize TCM on other lands managed by USBLM, and by other government and private entities. Challenges are sure to emerge—especially given the potential mandate to coordinate among 13 Tribes—but with TCM still in its early developmental stages, every good-faith TCM initiative is guaranteed to boost understanding of opportunities for Tribes to reclaim stewardship for and relationship with Territory.

How Can I Learn More about TCM?

In addition to the in-text links included above, all of which are open access, the following is a list of references cited and other recommended resources for planning and implementing TCM, most of which are open access.

Diver, Sibyl (2016) Co-management as a Catalyst: Pathways to Post-Colonial Forestry in the Klamath Basin, California. Human Ecology 44(5):533–546. https://doi:10.1007/s10745-016-9851-8

Hoffmann, Hilary M., and Monte Mills (2020) A Third Way: Decolonizing the Laws of Indigenous Cultural Protection. Cambridge University Press.

Mills, Monte, and Martin Nie (2020) Bridges to a New Era; A Report on the Past, Present, and Potential Future of Tribal Co-Management on Federal Public Lands (Missoula, MT: Margery Hunter Brown Indian Law Clinic/Bolle Center for People and Forests, University of Montana). https://ak.audubon.org/sites/default/files/bridges_to_a_new_era_by_mills.nie_2020.pdf.

Pinel, Sandra L., and Jacob Pecos (2012) Generating Co-Management at Kasha Katuwe Tent Rocks National Monument, New Mexico. Environmental Management 49:593–604. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-012-9814-9

Pinkerton, Evelyn (2019) Benefits of collaboration between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities through community forests in British Columbia. Canadian Journal of Forestry Research 49:387–394. http://dx.doi.org/10.1139/cjfr-2018-0154

Redvers, Nicole; Poelina, Anne; Schultz, Clinton; Kobei, Daniel M.; Githaiga, Cicilia; Perdrisat, Marlikka; Prince, Donald; Blondin, Be’sha (2020) Indigenous Natural and First Law in Planetary Health. Challenges 11(2):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe11020029

Tipa, Gail, and Richard Welch (2006) Comanagement of Natural Resources: Issues of Definition from an Indigenous Community Perspective. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 42(3):373–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886306287738.

U.S. Bureau of Land Management (2004) Kasha-Katuwe Tent Rocks National Monument Science Plan. USBLM New Mexico State Office, Albuquerque. http://npshistory.com/publications/blm/kasha-katuwe-tent-rocks/sp-2020.pdf

Washburn, Wilcomb E. (1988) History of Indian-White Relations (Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 4). Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Weiss, Kristen, Mark Hamann, and Helene Marsh (2012) Bridging Knowledges: Understanding and Applying Indigenous and Western Scientific Knowledge for Marine Wildlife Management. Society & Natural Resources: An International Journal. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2012.690065.

Wright, Aaron M., and Maren P. Hopkins (2016) The Great Bend of the Gila: Contemporary Native American Connections to an Ancestral Landscape. Archaeology Southwest, Tucson, Az. https://www.archaeologysouthwest.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/gb_ethno.pdf.

Acknowledgments

The authors and Archaeology Southwest acknowledge the following persons for their time, energy, and knowledge in contributing to this position paper:

Joshua Watts, Archaeology Southwest, cyberSW Manager

Caitlynn Mayhew (Diné), Archaeology Southwest, cyberSW Native American Fellow

Aaron Wright, Archaeology Southwest, Preservation Anthropologist

Bill Doelle, Archaeology Southwest, Senior Advisor

The authors welcome feedback; email John Welch or Skylar Begay.