Photo Essay by Henry D. Wallace

An online exclusive supplement to Archaeology Southwest Magazine Vol. 27, No. 4

Western Archaic Tradition petroglyphs comprise the most ancient rock art of the Little Colorado region, dating to at least several thousand years B.C., and possibly as many as 9,000 years B.C., based on dated sites elsewhere in the western United States. As a “style,” it is widely distributed; indeed, it is nearly universal in distribution, and its designs are probably rooted in the biology of our brains. It is much less common than its more recent counterparts in the Silver Creek region.

“Walk this way.” Sometimes, the function of petroglyphs in the Middle Little Colorado River region is completely clear. This panel with a well-pecked Palavayu-style footprint and attached squiggly line shows exactly where to climb the canyon wall in order to readily leave a steep-walled canyon tributary of Silver Creek. Such access points are rare, and almost all are marked by rock art ranging from footprints like these to depictions of lines of deer.

Palavayu, a Hopi term meaning “red river,” is a name applied to several style designations of a kind of rock art that is only found in the middle portion of the lower Little Colorado River area.

Ghostly Palavayu Linear Style anthropomorphic figures watch over a deer passing along Silver Creek. Seen particularly clearly in the leftmost figure, these Palavayu figures are closely related to the Glen Canyon Linear Style (also known as Glen Canyon Style 5), which is thought to date between 3000 and 400 B.C.

Palavayu Linear Style birds on a panel along Silver Creek. The figure on the right has extraordinarily elongated legs. Palavayu Linear Style displays a host of different zoomorphic and reptilian figures, including birds, deer, snakes, and owls. Also visible on this panel are at least eleven bullet impact spalls, one of which affects the tail of the bird on the right. Unfortunately, such vandalism is common.

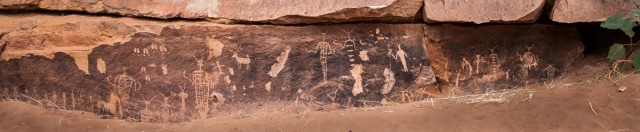

A spectacular petroglyph gallery partially buried and hidden in a sheltered area along one of the tributary accesses into Silver Creek Canyon. A wide range of Palavayu Linear shamanic figures accompany a flute player. This probably dates to Pueblo II or III (between A.D. 920 and 1350). Because Palavayu Linear figures are sometimes produced in later times, it is possible this entire panel postdates the original style.

Extraordinary panel with dozens of Palavayu Linear anthropomorphic skeletal figures along a rarely visited portion of Silver Creek. Differences in design patination are at least partly a function of different exposures along the large rock face.

Pair of Palavayu Linear Style anthropomorphic figures rising out of a small tributary canyon along Silver Creek. Many of the shamanic figures of the Palavayu Linear Style give the illusion of flight and upward movement—perhaps none so clearly as these.

Portion of another large panel with many Palavayu Linear Style anthropomorphic figures showing their close proximity on the canyon walls to Silver Creek. Palavayu anthropomorphic figures commonly have skeletal bodies and heads; they are often missing legs and sometimes arms; and they commonly depict “antennae” rising from the heads. The skeletal form suggests the depiction of death, whereas the illusion of flight or rising suggests rebirth or shamanic flight. Because shamans typically experience “death” during their ceremonies, some researchers consider these figures to be shamanic in origin. Although sometimes copied in Pueblo II (A.D. 920–1150) rock art, by then—and certainly by Pueblo III—anthropomorphic figures became less surreal and more concrete. Gone were the skeletal figures, replaced by figures depicted with realistic hair. A clear change in rock art reflects other patterns of culture change seen with the rise of sedentism in the region.

A Palavayu Linear Style anthropomorphic figure positioned along Silver Creek and marking an access point. The shamanic figures of the Palavayu Style have much in common with other anthropomorphic figure types and accoutrements found throughout the Colorado Plateau and into southern Utah, and even as far as the Lower Pecos in Texas. Throughout these regions, early figurative styles found in canyons and rock shelters are characterized by human figures with elongate triangular bodies, unusual head attachments, and bodies filled with designs or hachure or both. The snake-like item in this figure’s left hand is often seen in art known from southern Utah that also dates before A.D. 1.