Hohokam or Huhugam?

Archaeologists call the ancient people of the Sonoran Desert “Hohokam.” The O’odham people living in the region today refer to their ancestors as Huhugam. Although “Hohokam” and Huhugam are similar in spelling and pronunciation, they have distinctly different meanings.

Important questions in Hohokam research have focused on what happened to these ancient groups and how they are related to modern Native Americans. The observation that they vanished from the archaeological record centuries ago, yet have living descendants in the area, has long posed a dilemma for archaeologists.

In this exhibit, the term Hohokam is used as a type of archaeological “shorthand” to refer to particular ancient groups based on distinct pottery manufacturing techniques, architectural traditions, and other customs. Hohokam, as an archaeological term, is limited to a specific time period. Huhugam is more inclusive.

Hohokam traditions changed and eventually disappeared as immigrants arrived and the region’s population declined over many generations. The few people still living in the area during the 15th century are not considered part of the Hohokam archaeological culture, because their pottery, architecture, and other traditions had changed. Nonetheless, they were Huhugam, the ancestors of the O’odham.

O’odham explanation of the term Huhugam

Odham Elder Barnaby V. Lewis of the Gila River Indian Community explains the meaning of the O’odham word Huhugam:

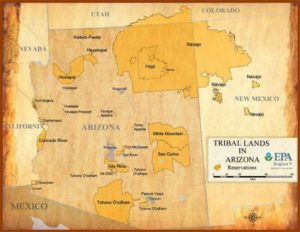

The O’odham of central and southern Arizona are represented by four separate federally recognized tribal governments that include O’odham of the Gila River Indian Community, the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community, the Ak-Chin Indian Community and the Tohono O’odham Nation. O’odham of the Tohono O’odham Nation also occupy lands at San Lucy in Gila Bend, Florence Village east of Florence, and the San Xavier District Community in Tucson.

The O’odham have a familial relationship of shared cultural group identity that can be traced historically and prehistorically to the Huhugam that inhabited central and southern Arizona, as well as the northern region of present-day Mexico.

From published literature, the O’odham word Huhugam was first recorded in 1694 upon the discovery of Sivan Vahki (also known as Casa Grande Ruins) and in later years appeared in various documents such as the O’odham oral narratives written down in 1775 by Father Pedro Font.

The historic translation of Huhugam as recorded by ethnographers and archaeologists basically accepts an interpretation provided by O’odham informant(s) in 1908. The recorded translations that are attributed to the O’odham word Huhugam are incorrect. The limited knowledge of the English language on the part of the informant(s) and the context of the conversations may account for the misleading interpretations.

Huhugam does not literally mean “the things that are all used up.” Huhugam specifically applies to past human life and not objects as in the generally accepted translation, “that which has perished” (Haury 1976:5). The term “that” implies reference to an object, which is inaccurate and is not acceptable in the hearts and minds of the present-day O’odham.

Huhugam is not the same as the archaeological term Hohokam, which is limited by time periods and does not represent the true reverent acknowledgement of ancient ancestors, as well as living O’odham who will become ancestors today or tomorrow.

In the O’odham traditional view, Huhugam is used in referring to O’odham ancestors, identifying a person(s) from whom an individual(s) is a lineal descendant. The O’odham family tree is inclusive of all O’odham. This has been related not by one particular person, but has as its basis the Creation story that places the existence of life on earth from time immemorial.

The O’odham are primarily an oral history society. O’odham origins and history are recorded through oration and are passed from one generation to the next by practice of known traditional protocols to memorialize significant events in the passage of time. O’odham oral traditions identify Huhugam as the ancestral relatives of the present-day O’odham, and that knowledge is essentially the core of O’odham cultural identity. It may be best for the public to recognize that Huhugam and Hohokam are both in union as one in a spiritual realm of the past.

This perspective represents the understanding and beliefs of Odham Elder Barnaby V. Lewis of the Gila River Indian Community, December 2008.

Hohokam Traditions and Lifestyles

Between A.D. 450 and 1150, Hohokam homes were “pit houses.” People dug shallow pits and built houses inside. Wooden wall posts and roof beams formed structures that were covered with grass and adobe. These houses were arranged in courtyard groups, such that doorways faced each other and opened onto a common central area. By 1150, people were building rooms above ground. The rooms were connected by walls that enclosed adjacent courtyard spaces. Archaeologists refer to these constructions as compounds.

At some Hohokam villages dating between A.D. 700 and 1100, people created sunken ballcourts. Watching or participating in ball games brought people together, and provided opportunities to visit with friends and family and trade raw materials and finished goods, such as pottery vessels. By 1200, people had begun building rectangular, straight-sided, flat-topped structures called platform mounds. Rituals conducted on top of platform mounds were visible to spectators below.

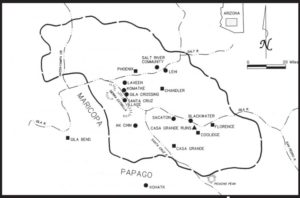

Throughout their long occupation of the area, the Hohokam practiced intensive irrigation agriculture. The network of irrigation canals in the Phoenix area was the largest and most complex in ancient North America.

Key Points:

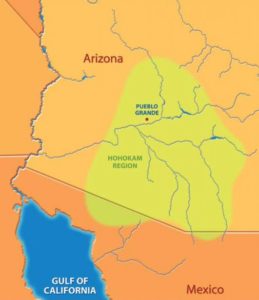

Hohokam is the name of an archaeological culture. It refers to people who lived in parts of central and southern Arizona between A.D. 450 and 1450.

Hohokam is not the same as Huhugam. Huhugam is an O’odham word for all O’odham ancestors, including those known to archaeologists as the Hohokam.

Hohokam groups practiced irrigation agriculture and built complex canal systems. Their architectural, pottery-making, and mortuary traditions distinguish them from other ancient groups in the Southwest.