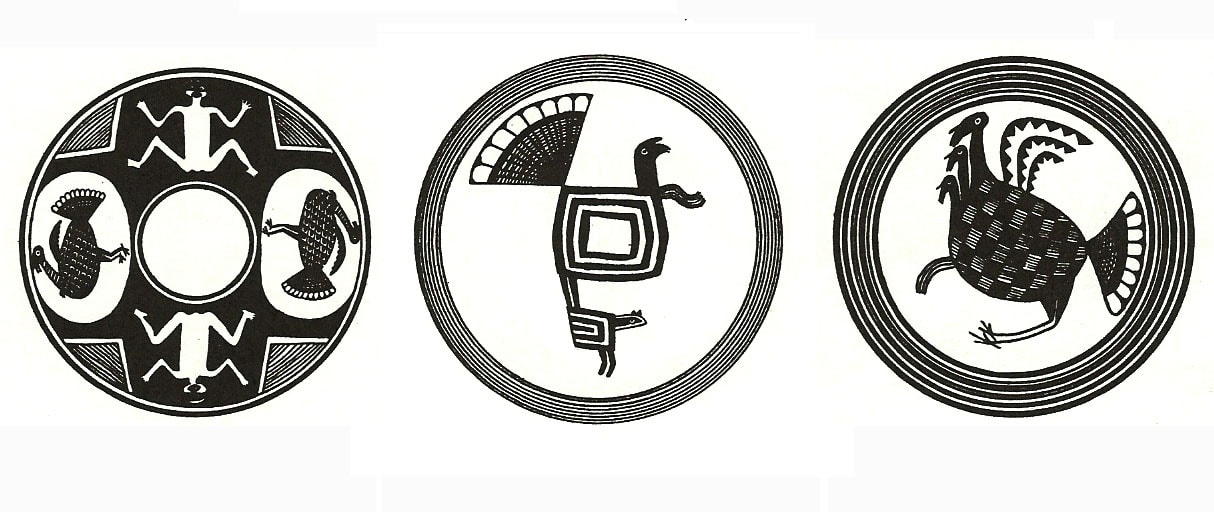

The Mimbres region of the American Southwest is celebrated for the beautiful and expressive black-on-white pottery made there in the distant past. Archaeologists often use the term “Mimbres culture” to refer generally to groups who lived in the region and produced Mimbres Black-on-white pottery. Mimbres culture is included in the broader Mogollon tradition found in the mountains and plateus of the central Southwest.

Unfortunately, extensive commercial looting aimed at finding and selling Mimbres pottery devastated many of the region’s sites over the last century. Nevertheless, archaeologists have learned a lot about the region’s ancient inhabitants by working with landowners and land managers to rehabilitate looted sites and protect intact sites.

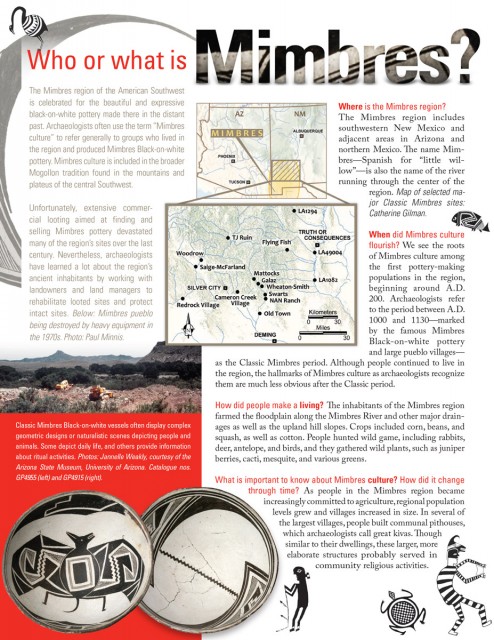

Where is the Mimbres region?

The Mimbres region includes southwestern New Mexico and adjacent areas in Arizona and northern Mexico. The name Mimbres— Spanish for “little willow”—is also the name of the river running through the center of the region.

When did Mimbres culture flourish?

We see the roots of Mimbres culture among the first pottery-making populations in the region, beginning around A.D. 200. Archaeologists refer to the period between A.D. 1000 and 1130—marked by the famous Mimbres Black-on-white pottery and large pueblo villages—as the Classic Mimbres period. Although people continued to live in the region, the hallmarks of Mimbres culture as archaeologists recognize them are much less obvious after the Classic period.

How did people make a living?

The inhabitants of the Mimbres region farmed the floodplain along the Mimbres River and other major drainages as well as the upland hill slopes. Crops included corn, beans, and squash, as well as cotton. People hunted wild game, including rabbits, deer, antelope, and birds, and they gathered wild plants, such as juniper berries, cacti, mesquite, and various greens.

What is important to know about Mimbres culture? How did it change through time?

As people in the Mimbres region became increasingly committed to agriculture, regional population levels grew and villages increased in size. In several of the largest villages, people built communal pithouses, which archaeologists call great kivas. Though similar to their dwellings, these larger, more elaborate structures probably served in community religious activities.

Dramatic changes occurred over the course of the tenth century. In the early 900s, people disassembled most of the great kivas and burned them in fires that would have been visible for miles. By about 1000, people had begun building aboveground pueblos instead of the pithouses of earlier time periods. Some of these contained several hundred rooms, representing some of the largest villages in the Southwest at that time. These changes coincided with the elaboration of painted designs on Mimbres Black-on-white pottery, marking the beginning of what archaeologists call the Classic Mimbres period.

Thousands of people lived in the Mimbres region in this period, building remarkably similar houses, preparing and cooking food in similar ways, and painting similar designs on pottery that served in daily activities and funerary rituals. Communities seem to have been somewhat insular, with very few trade goods to show connections to other parts of the Southwest, yet images on pottery (such as ocean-dwelling fish) suggest that they had knowledge of more distant lands.

Population increased until the early 1100s, when people began to leave a number of villages, especially those within the Mimbres Valley and the Upper Gila. Increased food stress driven by high population levels, social problems in increasingly large villages, and a period of poor climatic conditions may have contributed to this widespread departure. By about 1130, potters stopped making the black-on-white pottery that had been the region’s hallmark. Previously, archaeologists viewed these as signs of collapse. More recently, as researchers have investigated areas outside of the central Mimbres Valley, we see considerable evidence that people remained in those outlying areas. The locations and layouts of settlements changed, however, and there was a great deal more diversity in pottery and architecture. Imported pottery shows that these later residents established connections with distant areas of the Southwest and northern Mexico. Population continued to decline through 1450, however, by which time prehistoric agricultural populations seem to have completely abandoned the Mimbres region.

What is happening to Mimbres sites today?

Thanks to the efforts of archaeologists and concerned landowners, as well as new state and federal laws, Mimbres sites are no longer on the path toward total obliteration. Since the 1970s, the nonprofit Mimbres Foundation has protected and investigated a number of important sites across the Mimbres region. In 2011, Archaeology Southwest took on the responsibilities for protecting three of these sites—Mattocks, Janss, and Wheaton-Smith—and we continue to work with private and public partners to ensure the protection of others.

Want to learn more? Explore the major concepts, places, cultures, and themes that Southwestern archaeologists are investigating today in our Introduction to Southwestern Archaeology.