Preserving Archaeological Landscapes

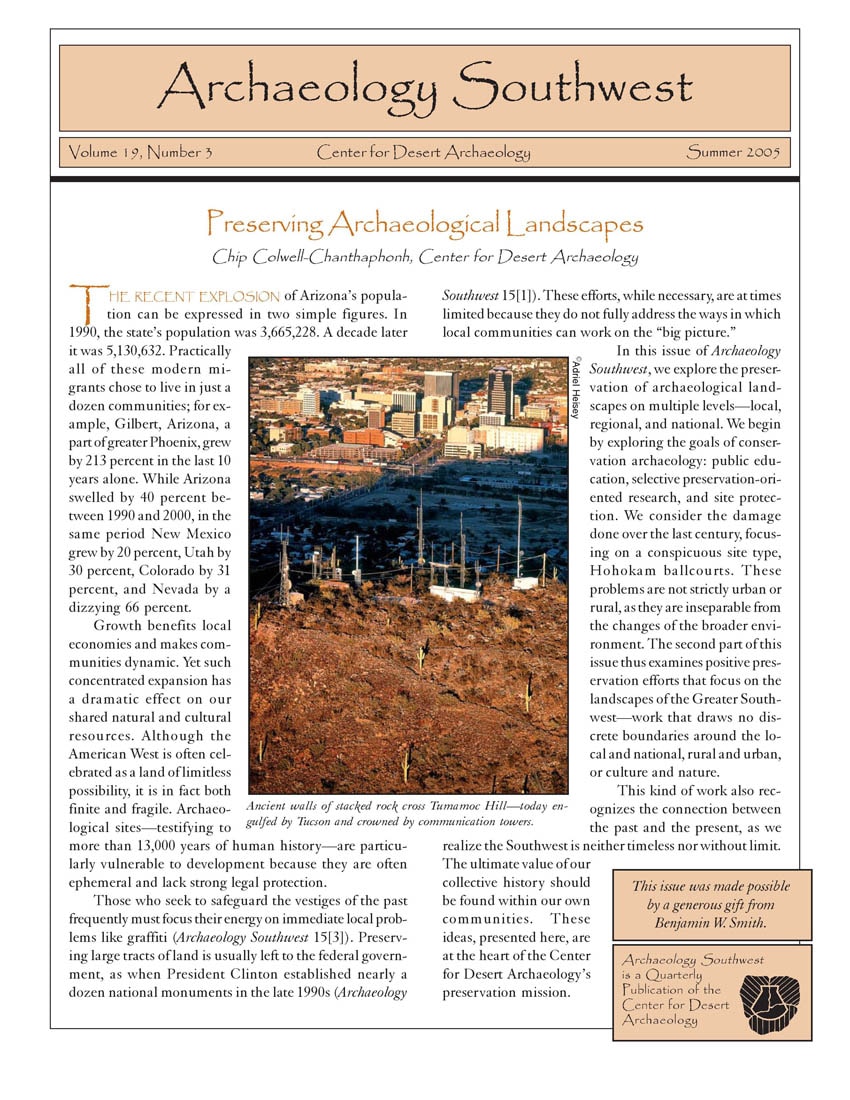

Ancient walls of stacked rock cross Tumamoc Hill–today engulfed by Tucson and crowned by communication towers. Image copyright Adriel Heisey.

Volume 19, Number 3

FREE PDF DOWNLOAD

Chip Colwell-Chanthaphonh, Center for Desert Archaeology

The recent explosion of Arizona’s population can be expressed in two simple figures. In 1990, the state’s population was 3,665,228. A decade later it was 5,130,632. Practically all of these modern migrants chose to live in just a dozen communities; for example, Gilbert, Arizona, a part of greater Phoenix, grew by 213 percent in the last 10 years alone. While Arizona swelled by 40 percent between 1990 and 2000, in the same period New Mexico grew by 20 percent, Colorado by 31 percent, and Nevada by a dizzying 66 percent.

Growth benefits local economies and makes communities dynamic. Yet such concentrated expansion has a dramatic effect on our shared natural and cultural resources. Although the American West is often celebrated as a land of limitless possibility, it is in fact both finite and fragile. Archaeological sites–testifying to more than 13,000 years of human history–are particularly vulnerable to development because they are often ephemeral and lack strong legal protection.

In this issue of Archaeology Southwest, we explore the preservation of archaeological landscapes on multiple levels–local, regional, and national. We begin by exploring the goals of conservation archaeology: public education, selective preservation-oriented research, and site protection. We consider the damage done over the last century, focusing on a conspicuous site type, Hohokam ballcourts. These problems are not strictly urban or rural, as they are inseparable from the changes of the broader environment. The second part of this issue thus examines positive preservation efforts that focus on the landscapes of the Greater Southwest–work that draws no discrete boundaries around the local and national, rural and urban, or culture and nature.

This kind of work also recognizes the connection between the past and the present, as we realize the Southwest is neither timelss nor without limit. The ultimate value of our collective history should be found within our own communities. These ideas, presented here, are at the heart of the Center for Desert Archaeology’s preservation mission.

This issue was made possible by a generous gift from Benjamin W. Smith.

Articles include:

- Preserving Archaeological Landscapes – Chip Colwell-Chanthaphonh, Center for Desert Archaeology

- A Conservation Model for Archaeology – William D. Lipe, Washington State University

- Hohokam Ballcourt Villages in Peril – William H. Doelle, Center for Desert Archaeology

- Growth of Greater Phoenix

- O’odham Ancestral Lands – Barnaby V. Lewis, Cultural Resource Management Program, Gila River Indian Community

- Palo Verde Open Space – Mark Hackbarth, Logan Simpson Design, and Jeffrey Sargent, City of Peoria

- The Las Vegas Springs Preserve

- The Santa Lucia Ranch and Rancho Seco – Diana Freshwater, Arizona Open Land Trust

- Archaeological Conservation Easements – Jacquie M. Dale, Center for Desert Archaeology

- The Buried City Site in Texas

- Saving Sites, Preserving Communities – James B. Walker, The Archaeological Conservancy

- Cultural Resources Preservation by Pima County – Roger Anyon and Linda L. Mayro, Pima County Cultural Resources

- New Mexico Tax Credit for Archaeological Site Protection

- The Arizona Site Steward Program – Mary Estes, Arizona State Historic Preservation Office

- The Spur Cross Ranch Conservation Area

- A Holistic Approach to Preservation Law Enforcement – Patrick D. Lyons, Center for Desert Archaeology

- National Heritage Areas – Anne J. Goldberg, Center for Desert Archaeology

- Urban Parks in Tucson, Arizona

- Back Sight – William H. Doelle, Center for Desert Archaeology

Subscribe